Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

BeyondGeography

BeyondGeography's Journal

BeyondGeography's Journal

September 30, 2019

Two noteworthy bits from UFCW President Marc Perrone at the end:

"I can't believe the amount of energy you bring to the table."

And:

"Do you golf?"

"No."

"Well, great, we'll have a full-time President then."

Warren was pretty much non-stop great at the UFCW forum yesterday

This runs for about a half-hour. She comes on at around the 29-minute mark:

Two noteworthy bits from UFCW President Marc Perrone at the end:

"I can't believe the amount of energy you bring to the table."

And:

"Do you golf?"

"No."

"Well, great, we'll have a full-time President then."

September 30, 2019

GOP Rep. Kinzinger slams Trump for quoting pastor's civil war remarks

https://twitter.com/RepKinzinger/status/1178489464504619013

September 29, 2019

A cold call from someone she never met changed Elizabeth Warren's life. It was Harry Reid.

WASHINGTON — Elizabeth Warren was a professor at Harvard Law School, preparing barbecue and peach cobbler for a group of students expected at her home. The phone rang. The owner of the faint voice on the other end of the line was well known, but they had never met.

"Who?" Warren asked.

"Harry Reid," he replied. "Majority leader, U.S. Senate."

That was November 2008, when the economy was imploding, and Reid was offering her a spot on a new commission overseeing the Wall Street bailout Congress had just approved. Would she take it? he asked. At the time, Professor Warren was blogging for Talking Points Memo and about as well known as a policy wonk can be — which is to say not very. She had expressed zero political ambition, never run for office and her only real brush with Washington ended years earlier in a demoralizing loss when Congress passed a bankruptcy bill over her objections.

Reid's Congressional Oversight Panel came with a memorable acronym, COP, but had little real power. It essentially had one job: "Submit reports." Still, Warren said yes right away and so began "When Harry met Liz," a political saga that continues to this day.

“Everyplace she's been, she's been extremely good, for lack of a better way to explain it," the understated Reid told NBC News in an interview. Warren said in a statement, "Since then, we've been fighting the good fight — and Harry is someone you always want in your corner.”

...While Warren came to Washington just weeks after the election of Barack Obama, it was Reid who first plucked her from relative obscurity in academia and later championed her Senate bid. "He would always ask about her," said Guy Cecil, who ran the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee at the time and is now chairman of the party's largest super PAC, Priorities USA. "And he was always much more bullish on her than a lot of people in Massachusetts."

...The Mormon ex-cop who started his career as a conservative Democrat may make for an unlikely match with the crusading progressive Ivy League prof. But they shared hardscrabble roots in the American West and the economic populism of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Warren keeps a bust of FDR in her Senate office while Reid has recalled how one of his mother's few prized possessions was a pillowcase embroidered with an FDR quote that hung on the wall of their ramshackle house that lacked indoor plumbing.

"He loves someone with a good story. Someone who's overcome hardship like he has, someone who's worked their ass off like Elizabeth Warren has," said Rebecca Katz, a Democratic strategist who used to work for Reid. "When he believes in you, he will fight for you." And after Reid named her to the oversight panel, he felt invested in her career.

More at https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2020-election/cold-call-someone-she-never-met-changed-elizabeth-warren-s-n1057926

"Who?" Warren asked.

"Harry Reid," he replied. "Majority leader, U.S. Senate."

That was November 2008, when the economy was imploding, and Reid was offering her a spot on a new commission overseeing the Wall Street bailout Congress had just approved. Would she take it? he asked. At the time, Professor Warren was blogging for Talking Points Memo and about as well known as a policy wonk can be — which is to say not very. She had expressed zero political ambition, never run for office and her only real brush with Washington ended years earlier in a demoralizing loss when Congress passed a bankruptcy bill over her objections.

Reid's Congressional Oversight Panel came with a memorable acronym, COP, but had little real power. It essentially had one job: "Submit reports." Still, Warren said yes right away and so began "When Harry met Liz," a political saga that continues to this day.

“Everyplace she's been, she's been extremely good, for lack of a better way to explain it," the understated Reid told NBC News in an interview. Warren said in a statement, "Since then, we've been fighting the good fight — and Harry is someone you always want in your corner.”

...While Warren came to Washington just weeks after the election of Barack Obama, it was Reid who first plucked her from relative obscurity in academia and later championed her Senate bid. "He would always ask about her," said Guy Cecil, who ran the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee at the time and is now chairman of the party's largest super PAC, Priorities USA. "And he was always much more bullish on her than a lot of people in Massachusetts."

...The Mormon ex-cop who started his career as a conservative Democrat may make for an unlikely match with the crusading progressive Ivy League prof. But they shared hardscrabble roots in the American West and the economic populism of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Warren keeps a bust of FDR in her Senate office while Reid has recalled how one of his mother's few prized possessions was a pillowcase embroidered with an FDR quote that hung on the wall of their ramshackle house that lacked indoor plumbing.

"He loves someone with a good story. Someone who's overcome hardship like he has, someone who's worked their ass off like Elizabeth Warren has," said Rebecca Katz, a Democratic strategist who used to work for Reid. "When he believes in you, he will fight for you." And after Reid named her to the oversight panel, he felt invested in her career.

More at https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2020-election/cold-call-someone-she-never-met-changed-elizabeth-warren-s-n1057926

September 28, 2019

Russia tells US not to release Trump-Putin transcripts

Russia on Friday urged the United States not to publish Donald Trump's conversations with Vladimir Putin after a growing scandal led the White House to release a transcript from a call with Ukraine's leader.

"As for transcripts of phone conversations, my mother when bringing me up said that reading other people's letters is inappropriate," Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov told reporters at the United Nations. "It is indecent," he said. "For two people elected by their nations to be at the helm, there are diplomatic manners that suppose a certain level of confidentiality."

The White House on Wednesday put out a summary of a July 25 call with Ukraine's newly elected president, Volodymyr Zelensky, after controversy over the conversation led rival Democrats to launch an impeachment process. It showed that Trump asked Zelensky to probe Democratic rival Joe Biden, and Democrats are looking into whether Trump used a delayed $400 million aid package as leverage.

Lavrov, who met Friday with Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, criticised both US lawmakers and media for the release of the transcript.

"Being so vociferous in saying that if you don't show a certain memo involving a partner, that you're going to bring this administration to its knees, what kind of democracy is that? How can you work in such conditions?" he said.

https://www.news24.com/World/News/russia-tells-us-not-to-release-trump-putin-transcripts-20190928

"As for transcripts of phone conversations, my mother when bringing me up said that reading other people's letters is inappropriate," Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov told reporters at the United Nations. "It is indecent," he said. "For two people elected by their nations to be at the helm, there are diplomatic manners that suppose a certain level of confidentiality."

The White House on Wednesday put out a summary of a July 25 call with Ukraine's newly elected president, Volodymyr Zelensky, after controversy over the conversation led rival Democrats to launch an impeachment process. It showed that Trump asked Zelensky to probe Democratic rival Joe Biden, and Democrats are looking into whether Trump used a delayed $400 million aid package as leverage.

Lavrov, who met Friday with Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, criticised both US lawmakers and media for the release of the transcript.

"Being so vociferous in saying that if you don't show a certain memo involving a partner, that you're going to bring this administration to its knees, what kind of democracy is that? How can you work in such conditions?" he said.

https://www.news24.com/World/News/russia-tells-us-not-to-release-trump-putin-transcripts-20190928

September 27, 2019

Americans' Health-Care Costs Are Too Damn High, Study Finds

...the primary obstacle to rebuilding our ramshackle health-care system is the immense power of the industries and interest groups that have monetized its rot. But historically, public opinion has posed its own discrete challenges. Voters often display a strong sense of loss aversion, valuing the preservation of what they have over the uncertain promise of something better. And in the domain of health care — where the stakes of losing what one has (if one is privileged enough to have coverage in the general vicinity of “affordable”) are potentially life and death — this tendency has been especially acute.

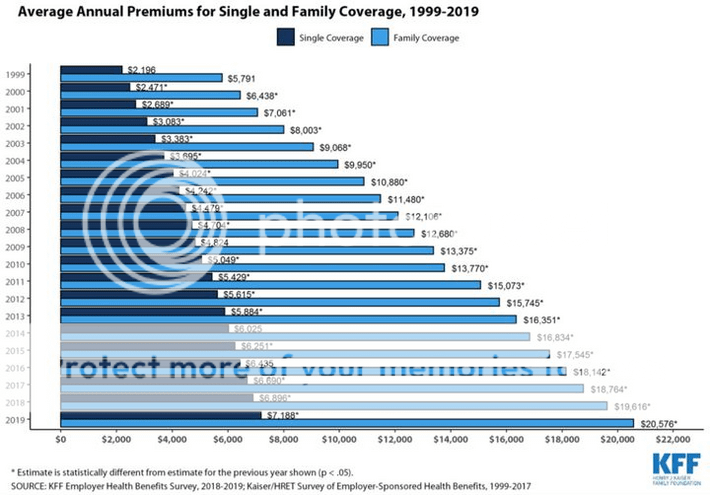

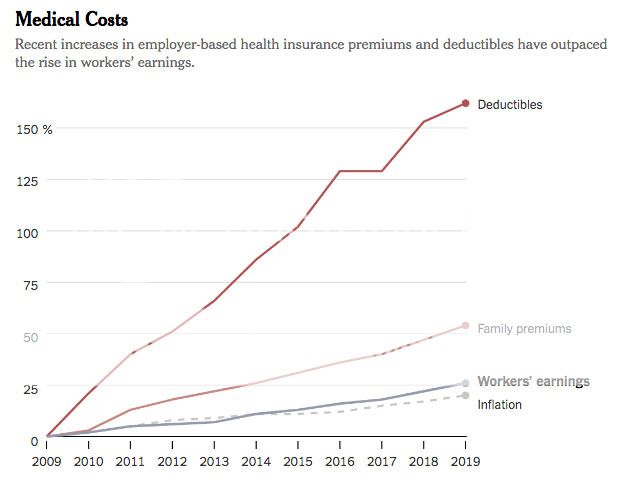

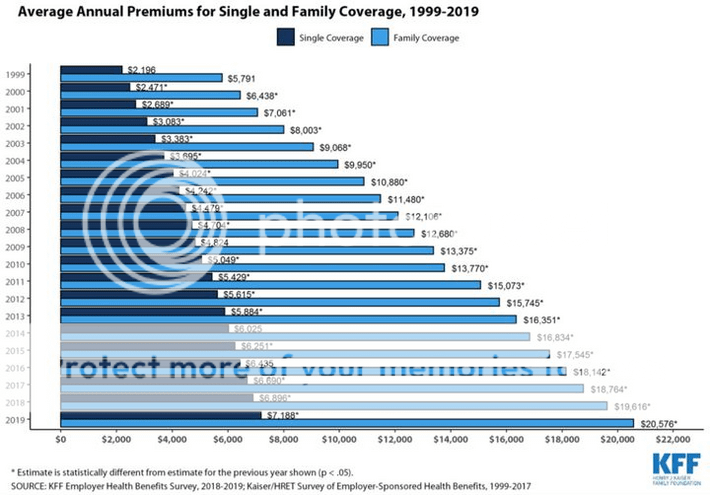

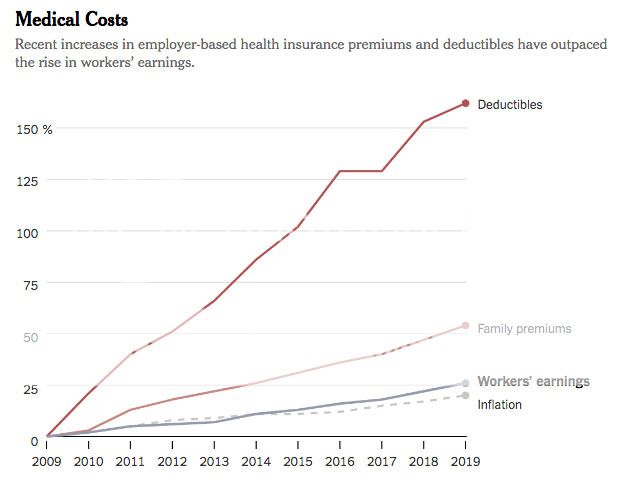

...For these reasons, a lot of health-care punditry presumes that the public’s appetite for Medicare for All — or even a Medicare buy-in — will swiftly decline once Democrats have the opportunity to actually implement it. And that scenario remains plausible. But there’s increasing reason to believe that “next time will be different” — because with each passing year, those loss-averse voters with employer-provided insurance have less and less to lose: According to KFF’s latest survey, the average annual premium for a job-based, family health-insurance plan is now $20,756 — 54 percent higher than it was just ten years ago. And the price of such plans is rising even faster for their actual beneficiaries, as employers offload rising health-care costs onto workers: Since 2009, the average premium paid by employees for a family plan has jumped by 71 percent to $6,015.

Among workers themselves, the distribution of the growing burden is deeply regressive. Since high-wage workers have more bargaining power than low-wage ones, firms force far more cost-sharing on the latter than the former. As a result, an increasing number of low-wage workers are forgoing employer-provided coverage. As Bloomberg notes:

In firms where more than 35% of employees earn less than $25,000 a year, workers would have to contribute more than $7,000 for a family health plan … Only one-third of employees at such firms are on their employer’s health plans, compared with 63% at higher-wage firms …

Some employers have opted to keep premiums affordable by diverting rising costs into higher deductibles, a policy that effectively takes from sick workers to give to healthy ones. Which goes over well with the median worker — right up until he or she moves from that second category to the first.

It is true that, for most of the decade documented here, American public opinion on health-care policy actually trended rightward. One could attribute that fact to the Affordable Care Act’s peculiar failures, or to thermostatic public opinion. Either way, it is an argument against the assumption that worsening objective conditions will necessarily build public support for radical reform.

Still, it’s hard not to think that there will eventually be a breaking point. Absent massive policy changes, things are going to get worse before they get better. As the boomer generation ages, it will consume more and more health-care services, thereby driving up their price. Meanwhile, the burgeoning demand for drugs that ease the burdens of senescence is leading Big Pharma to roll out exorbitantly expensive new medicines. These demographic-driven cost pressures aren’t unique to the U.S. But America’s uniquely weak cost controls make them harder to absorb. Under our existing system, the U.S. spends several times more than similar nations on health-care administration, pharmaceuticals, and physicians’ salaries. In return, Americans enjoy the 29th best health-care system in the world (just behind the Czech Republic’s), according to the Lancet.

More at:http://nymag.com/intelligencer/2019/09/kaiser-survey-premiums-america-health-care-costs-study.html

...For these reasons, a lot of health-care punditry presumes that the public’s appetite for Medicare for All — or even a Medicare buy-in — will swiftly decline once Democrats have the opportunity to actually implement it. And that scenario remains plausible. But there’s increasing reason to believe that “next time will be different” — because with each passing year, those loss-averse voters with employer-provided insurance have less and less to lose: According to KFF’s latest survey, the average annual premium for a job-based, family health-insurance plan is now $20,756 — 54 percent higher than it was just ten years ago. And the price of such plans is rising even faster for their actual beneficiaries, as employers offload rising health-care costs onto workers: Since 2009, the average premium paid by employees for a family plan has jumped by 71 percent to $6,015.

Among workers themselves, the distribution of the growing burden is deeply regressive. Since high-wage workers have more bargaining power than low-wage ones, firms force far more cost-sharing on the latter than the former. As a result, an increasing number of low-wage workers are forgoing employer-provided coverage. As Bloomberg notes:

In firms where more than 35% of employees earn less than $25,000 a year, workers would have to contribute more than $7,000 for a family health plan … Only one-third of employees at such firms are on their employer’s health plans, compared with 63% at higher-wage firms …

Some employers have opted to keep premiums affordable by diverting rising costs into higher deductibles, a policy that effectively takes from sick workers to give to healthy ones. Which goes over well with the median worker — right up until he or she moves from that second category to the first.

It is true that, for most of the decade documented here, American public opinion on health-care policy actually trended rightward. One could attribute that fact to the Affordable Care Act’s peculiar failures, or to thermostatic public opinion. Either way, it is an argument against the assumption that worsening objective conditions will necessarily build public support for radical reform.

Still, it’s hard not to think that there will eventually be a breaking point. Absent massive policy changes, things are going to get worse before they get better. As the boomer generation ages, it will consume more and more health-care services, thereby driving up their price. Meanwhile, the burgeoning demand for drugs that ease the burdens of senescence is leading Big Pharma to roll out exorbitantly expensive new medicines. These demographic-driven cost pressures aren’t unique to the U.S. But America’s uniquely weak cost controls make them harder to absorb. Under our existing system, the U.S. spends several times more than similar nations on health-care administration, pharmaceuticals, and physicians’ salaries. In return, Americans enjoy the 29th best health-care system in the world (just behind the Czech Republic’s), according to the Lancet.

More at:http://nymag.com/intelligencer/2019/09/kaiser-survey-premiums-america-health-care-costs-study.html

September 27, 2019

https://twitter.com/ewarren/status/1177354422088798208

A 19-year-old c-store employee could only donate $3 to Warren; she called to say thanks anyway

He is just 19-years-old, works at a Circle K, and lives pay check to pay check – but he really wanted to make a donation to the campaign of Democratic candidate Elizabeth Warren. He was only able to afford to donate $3, so was a little shocked when the candidate herself called him to say thanks.

The heartwarming call was shared on Warren’s Twitter page. When Zachary answers the phone, he simply says: “You’ve gotta be kidding me.”

More at https://www.pinknews.co.uk/2019/09/27/elizabeth-warren-gay-man-thank-you-call-donation-ohio/

The heartwarming call was shared on Warren’s Twitter page. When Zachary answers the phone, he simply says: “You’ve gotta be kidding me.”

More at https://www.pinknews.co.uk/2019/09/27/elizabeth-warren-gay-man-thank-you-call-donation-ohio/

https://twitter.com/ewarren/status/1177354422088798208

September 27, 2019

Revenge of the Intelligence Nerds

Trump has long worried that America’s intelligence professionals would try to undermine him from the shadows. All they had to do was play by the rules.On his first day in office, in January 2017, Donald Trump paid a visit to the CIA. He stood before its Memorial Wall, which then had 117 stars commemorating those who lost their lives in the line of duty. “I want to just let you know, I am so behind you,” Trump told the crowd of intelligence officials who’d gathered to hear him speak. “And I know maybe sometimes you haven’t gotten the backing that you’ve wanted, and you’re going to get so much backing,” he said, just days after comparing U.S. intelligence agencies to Nazis.

...The relationship became even more strained after Trump’s CIA visit. He repeatedly cast doubt on the conclusion by U.S. intelligence agencies that Russia interfered in the 2016 election to help him win. The Russia investigation led by Special Counsel Robert Mueller was a “witch hunt.” FBI members who looked into the Trump campaign’s dealings with Russia were partisan and possibly part of a conspiracy. Besides Russia, Trump also disagreed with U.S. intelligence assessments on North Korea and Iran. He faced a constant threat of sabotage from leakers. In Trump’s narrative, members of the intelligence community worked to undermine Trump from the shadows, the cloak-and-dagger henchmen of the “deep state.”

...In the end, though, it was someone playing by the rules who triggered perhaps the greatest reckoning of Trump’s presidency. The intelligence official who brought Trump’s misconduct in the Ukraine scandal to light—a CIA member who was detailed to the White House, according to a report in The New York Times—didn’t do it via press leaks, or by passing it to a sympathetic lawmaker. The whistle-blower went instead through the relatively straightforward and unexciting bureaucratic process of filing a complaint with the office of the intelligence community’s inspector general. Filing the complaint ensured that classified information would be protected, national-security concerns would be evaluated, and ultimately, the information would reach the proper authorities. This candid and somewhat mundane process, while flawed, was surprisingly effective at holding Trump to account.

...The key was its simplicity: By channeling the details of Trump’s misconduct into a formal complaint and then feeding it into the intelligence community’s system, the whistle-blower has thrown a wrench into Trump’s heretofore insurmountable deflect-by-chaos machine. As the scandal escalates, Trump and his White House seem to be in increasing disarray. He released a damaging reconstructed transcript of his July 25 call with Ukraine’s president, which left even some of his Republican allies scratching their heads. He threatened the whistle-blower’s sources in front of a room full of U.S. diplomatic staff. His communications team mistakenly emailed a strategy memo to Democratic lawmakers, then tried to recall the message. His personal lawyer, Rudy Giuliani, who is also implicated in the scandal, has tried to drag the State Department down with him, while also embarking on confusing rants in conversations with reporters.

Despite the White House’s best efforts, the fact that the whistle-blower filed a complaint through proper government channels has made it harder for the usual attacks about traitors and dirty tricks to stick. Michael Atkinson, the inspector general who handled the complaint, and Joseph Maguire, Trump’s recent appointment as acting director of national intelligence, have already come to the whistle-blower’s defense.

More at https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2019/09/how-whistle-blower-complaint-undermined-trump/598972/?utm_term=2019-09-27T17%3A11%3A00&utm_campaign=the-atlantic&utm_medium=social&utm_content=edit-promo&utm_source=twitter

...The relationship became even more strained after Trump’s CIA visit. He repeatedly cast doubt on the conclusion by U.S. intelligence agencies that Russia interfered in the 2016 election to help him win. The Russia investigation led by Special Counsel Robert Mueller was a “witch hunt.” FBI members who looked into the Trump campaign’s dealings with Russia were partisan and possibly part of a conspiracy. Besides Russia, Trump also disagreed with U.S. intelligence assessments on North Korea and Iran. He faced a constant threat of sabotage from leakers. In Trump’s narrative, members of the intelligence community worked to undermine Trump from the shadows, the cloak-and-dagger henchmen of the “deep state.”

...In the end, though, it was someone playing by the rules who triggered perhaps the greatest reckoning of Trump’s presidency. The intelligence official who brought Trump’s misconduct in the Ukraine scandal to light—a CIA member who was detailed to the White House, according to a report in The New York Times—didn’t do it via press leaks, or by passing it to a sympathetic lawmaker. The whistle-blower went instead through the relatively straightforward and unexciting bureaucratic process of filing a complaint with the office of the intelligence community’s inspector general. Filing the complaint ensured that classified information would be protected, national-security concerns would be evaluated, and ultimately, the information would reach the proper authorities. This candid and somewhat mundane process, while flawed, was surprisingly effective at holding Trump to account.

...The key was its simplicity: By channeling the details of Trump’s misconduct into a formal complaint and then feeding it into the intelligence community’s system, the whistle-blower has thrown a wrench into Trump’s heretofore insurmountable deflect-by-chaos machine. As the scandal escalates, Trump and his White House seem to be in increasing disarray. He released a damaging reconstructed transcript of his July 25 call with Ukraine’s president, which left even some of his Republican allies scratching their heads. He threatened the whistle-blower’s sources in front of a room full of U.S. diplomatic staff. His communications team mistakenly emailed a strategy memo to Democratic lawmakers, then tried to recall the message. His personal lawyer, Rudy Giuliani, who is also implicated in the scandal, has tried to drag the State Department down with him, while also embarking on confusing rants in conversations with reporters.

Despite the White House’s best efforts, the fact that the whistle-blower filed a complaint through proper government channels has made it harder for the usual attacks about traitors and dirty tricks to stick. Michael Atkinson, the inspector general who handled the complaint, and Joseph Maguire, Trump’s recent appointment as acting director of national intelligence, have already come to the whistle-blower’s defense.

More at https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2019/09/how-whistle-blower-complaint-undermined-trump/598972/?utm_term=2019-09-27T17%3A11%3A00&utm_campaign=the-atlantic&utm_medium=social&utm_content=edit-promo&utm_source=twitter

September 27, 2019

Warren's Plan to Check Lobbyists' Influence? Make Lawmakers Smarter

With too many lawmakers lacking in expertise, lobbyists have filled the void. Warren wants to reverse the trendWASHINGTON — A recovering lobbyist once told me a story about how he did his job. He said he would sometimes stand outside of a committee room before a hearing, and when a friendly member of Congress would walk by, he’d slip them some talking points to use in the hearing. Then he’d walk inside the hearing room, take his seat in the gallery, and watch as those talking points were spouted by the elected officials and put into the official record.

It’s an extreme example of an all-too-familiar phenomenon in Washington: Powerful industries and their well-paid lobbyists press their case with lawmakers and, over time, those lawmakers come to rely on the technical expertise and perspectives of the industries they oversee to make legislative decisions. As Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) puts it, “Today, members of Congress don’t have access to the latest science and evidence, and lobbyists working for corporate clients are quick to fill this vacuum and bend the ears of members of Congress to advance their own narrow interests.”

The newest plan rolled out by Warren’s presidential campaign is meant to shift the expertise back to Congress and the federal government and to wean lawmakers off of industry-funded research and talking points.

In “Strengthening Congressional Independence from Corporate Lobbyists,” Warren calls for reviving the Congressional Office of Technology Assessment, increasing funding for the Congressional Research Service and making salaries for Capitol Hill staffers more competitive to attract subject-matter experts who might otherwise go work in the private sector.

In her announcement, Warren recounts the 2010 legislative battle to reform Wall Street and create a consumer-protection bureau. She describes how the bank lobbyists “bombarded the members of Congress with complex arguments filled with obscure terms,” seeking to swamp lawmakers and their staffers with jargon and technical language in an effort to water down regulations aimed at preventing the next Wall Street crash. “While a big part of the problem is a broken campaign finance system, members of Congress aren’t just dependent on corporate lobbyist propaganda because they’re bought and paid for,” Warren explains. “It’s also because of a successful, decades-long campaign to starve Congress of the resources and expertise needed to independently evaluate complex public policy questions.”

More at https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/warren-lobbyists-corruption-office-technology-assessment-891544/

It’s an extreme example of an all-too-familiar phenomenon in Washington: Powerful industries and their well-paid lobbyists press their case with lawmakers and, over time, those lawmakers come to rely on the technical expertise and perspectives of the industries they oversee to make legislative decisions. As Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) puts it, “Today, members of Congress don’t have access to the latest science and evidence, and lobbyists working for corporate clients are quick to fill this vacuum and bend the ears of members of Congress to advance their own narrow interests.”

The newest plan rolled out by Warren’s presidential campaign is meant to shift the expertise back to Congress and the federal government and to wean lawmakers off of industry-funded research and talking points.

In “Strengthening Congressional Independence from Corporate Lobbyists,” Warren calls for reviving the Congressional Office of Technology Assessment, increasing funding for the Congressional Research Service and making salaries for Capitol Hill staffers more competitive to attract subject-matter experts who might otherwise go work in the private sector.

In her announcement, Warren recounts the 2010 legislative battle to reform Wall Street and create a consumer-protection bureau. She describes how the bank lobbyists “bombarded the members of Congress with complex arguments filled with obscure terms,” seeking to swamp lawmakers and their staffers with jargon and technical language in an effort to water down regulations aimed at preventing the next Wall Street crash. “While a big part of the problem is a broken campaign finance system, members of Congress aren’t just dependent on corporate lobbyist propaganda because they’re bought and paid for,” Warren explains. “It’s also because of a successful, decades-long campaign to starve Congress of the resources and expertise needed to independently evaluate complex public policy questions.”

More at https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/warren-lobbyists-corruption-office-technology-assessment-891544/

September 25, 2019

Brahms Violin Concerto - Menuhin Lucerne Furtwangler

In which Yehudi Menuhin’s violin says, stop, I’m bleeding, I’ve given you my guts. And Menuhin responds, “No, I’m afraid Herr Furtwangler insists.”

An EMI “Record of the Century” (1949).

September 25, 2019

Mike Murphy on MSNBC: GOP Senator told me if it was a secret vote 30 of us would convict Trump

I think they’ll fold but getting their gutlessness on the record could give us the Senate in 2020.

Profile Information

Gender: MaleHometown: NY

Member since: Tue Dec 30, 2003, 12:41 AM

Number of posts: 39,369