Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

AsahinaKimi

AsahinaKimi's Journal

AsahinaKimi's Journal

December 31, 2012

Learn a little Japanese.. Language Lesson 1 Meeting

January 19, 2012

HATSUSHIMA ISLAND is probably unknown to all foreigners, and to 9999 out of every 10,000 Japanese; consequently, it is of not much importance. Nevertheless, it has produced quite a romantic little story, which was told to me by a friend who had visited there some six years before.

The island is about seven miles south-east of Atami, in Sagami Bay (Izu Province). It is so far isolated from the mainland that very little intercourse goes on with the outer world. Indeed, it is said that the inhabitants of Hatsushima Island are a queer people, and prefer keeping to themselves. Even today there are only some two hundred houses, and the population cannot exceed a thousand. The principal production of the island is, of course, fish; but it is celebrated also for its jonquil flowers (suisenn). Thus it will be seen that there is hardly any trade. What little the people buy from or sell to the mainland they carry in their own fishing-boats. In matrimony also they keep to themselves, and are generally conservative and all the better for it.

There is a well-known fisherman's song of Hatsushima Island. It means something like the following, and it is of the origin of that strange verse that the story is:—

Today is the tenth of June. May the rain fall in torrents!

For I long to see my dearest O Cho San.

Hi, Hi, Ya-re-ko-no-sa! Ya-re-ko-no-sa!

Many years ago there lived on the island the daughter of a fisherman whose beauty even as a child was extraordinary. As she grew, Cho—for such was her name—improved in looks, and, in spite of her lowly birth, she had the manners and refinement of a lady. At the age of eighteen there was not a young man on the island who was not in love with her. All were eager to seek her hand in marriage; but hardly any dared to ask, even through the medium of a third party, as was usual.

Amongst them was a handsome fisherman of about twenty years whose name was Shinsaku. Being less simple than the rest, and a little more bold, he one day approached Gisuke, O Cho's brother, on the subject. Gisuke could see nothing against his sister marrying Shinsaku; indeed, he rather liked Shinsaku; and their families had always been friends. So he called his sister O Cho down to the beach, where they were sitting, and told her that Shinsaku had proposed for her hand in marriage, and that he thought it an excellent match, of which her mother would have approved had she been alive. He added: 'You must marry soon, you know. You are eighteen, and we want no spinsters on Hatsushima, or girls brought here from the mainland to marry our bachelors.'

'Stay, stay, my dear brother! I do not want all this sermon on spinsterhood,' cried O Cho. 'I have no intention of remaining single, I can tell you; and as for Shinsaku I would rather marry him than any one else—so do not worry yourself further on that account. Settle the day of the happy event.'

Needless to say, young Gisuke was delighted, and so was Shinsaku; and they settled that the marriage should be three days thence.

Soon, when all the fishing-boats had returned to the village, the news spread; and it would be difficult to describe the state of the younger men's feelings. Hitherto every one had hoped to win the pretty O Cho San; all had lived in that happy hope, and rejoiced in the uncertain state of love, which causes such happiness in its early stages. Shinsaku had hitherto been a general favourite. Now the whole of their hopes were dashed to the ground. O Cho was not for any of them. As for Shinsaku, how they suddenly hated him! What was to be done? they asked one another, little thinking of the comical side, or that in any case O Cho could marry only one of them.

No attention was paid to the fish they had caught; their boats were scarcely pulled high enough on the beach for safety; their minds were wholly given to the question how each and every one of them could marry O Cho San. First of all, it was decided to tell Shinsaku that they would prevent his marriage if possible. There were several fights on the quiet beach, which had never before been disturbed by a display of ill-feeling. At last Gisuke, O Cho's brother, consulted with his sister and Shinsaku; and they decided, for the peace of the island, to break off the marriage, O Cho and her lover determining that at all events they would marry no one else.

However, even this great sacrifice had no effect. There were fully thirty men; in fact, the whole of the bachelors wanted to marry O Cho; they fought daily; the whole island was thrown into a discontent. Poor O Cho San! What could she do? Had not she and Shinsaku done enough already in sacrificing happiness for the peace of the island? There was only one more thing she could do, and, being a Japanese girl, she did it. She wrote two letters, one to her brother Gisuke, another to Shinsaku, bidding them farewell. 'The island of Hatsushima has never had trouble until I was born,' she said. 'For three hundred years or more our people, though poor, have lived happily and in peace. Alas! now it is no longer so, on account of me. Farewell! I shall be dead. Tell our people that I have died to bring them back their senses, for they have been foolish about me. Farewell!'

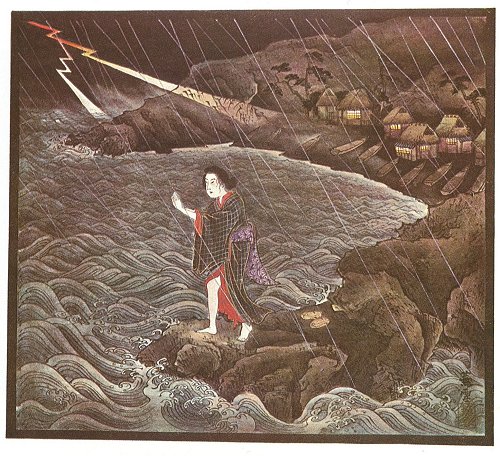

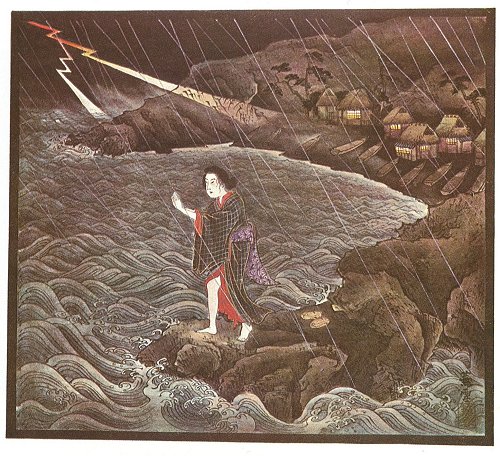

After leaving the two letters where Gisuke slept, O Cho slipped stealthily out of the house (it was a pouring-wet and stormy night and the 10th of June), and cast herself into the sea from some rocks near her cottage, after well loading her sleeves with stones, so that she might rise no more.

Next morning, when Gisuke found the letters, instinctively he knew what must have happened, and rushed from the house to find Shinsaku. Brother and lover read their letters together, and were stricken with grief, as, indeed, was every one else. A search was made, and soon O Cho's straw slippers were found on the point of rocks near her house. Gisuke knew she must have jumped into the sea here, and he and Shinsaku dived down and found her body lying at the bottom. They brought it to the surface, and it was buried just beyond the rocks on which she had last stood.

From that day Shinsaku was unable to sleep at night. The poor fellow was quite distracted. O Cho's letter and straw slippers he placed beside his bed and surrounded them with flowers. His days he spent decorating and weeping over her tomb.

At last one evening Shinsaku resolved to make away with his own body, hoping that his spirit might find O Cho; and he wandered towards her tomb to take a last farewell. As he did so he thought he saw O Cho, and called her aloud three or four times, and then with outstretched arms he rushed delightedly at her. The noise awoke Gisuke, whose house was close to the grave. He came out, and found Shinsaku clasping the stone pillar which was placed at its head.

Shinsaku explained that he had seen the spirit of O Cho, and that he was about to follow her by taking his life; but from this he was dissuaded.

'Do not do that; devote your life, rather, and I will help with you in building a shrine dedicated to Cho. You will join her when you die by nature; but please her spirit here by never marrying another.'

Shinsaku promised. The young men of the place now began to be deeply sorry for Shinsaku. What selfish beasts they had been! they thought. However, they would mend their ways, and spend all their spare time in building a shrine to O Cho San; and this they did. The shrine is called 'The Shrine of O Cho San of Hatsushima,' and a ceremony is held there every 10th of June. Curious to relate, it invariably rains on that day, and the fishermen say that the spirit of O Cho comes in the rain. Hence the song:—

Today is the tenth of June. May the rain fall in torrents!

For I long to see my dearest O Cho San.

Hi, Hi, Ya-re-ko-no-sa! Ya-re-ko-no-sa!

The shrine still stands, I am told.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/atfj/atfj29.htm

JAPANESE FOLK TALES~SAGAMI BAY

HATSUSHIMA ISLAND is probably unknown to all foreigners, and to 9999 out of every 10,000 Japanese; consequently, it is of not much importance. Nevertheless, it has produced quite a romantic little story, which was told to me by a friend who had visited there some six years before.

The island is about seven miles south-east of Atami, in Sagami Bay (Izu Province). It is so far isolated from the mainland that very little intercourse goes on with the outer world. Indeed, it is said that the inhabitants of Hatsushima Island are a queer people, and prefer keeping to themselves. Even today there are only some two hundred houses, and the population cannot exceed a thousand. The principal production of the island is, of course, fish; but it is celebrated also for its jonquil flowers (suisenn). Thus it will be seen that there is hardly any trade. What little the people buy from or sell to the mainland they carry in their own fishing-boats. In matrimony also they keep to themselves, and are generally conservative and all the better for it.

There is a well-known fisherman's song of Hatsushima Island. It means something like the following, and it is of the origin of that strange verse that the story is:—

Today is the tenth of June. May the rain fall in torrents!

For I long to see my dearest O Cho San.

Hi, Hi, Ya-re-ko-no-sa! Ya-re-ko-no-sa!

Many years ago there lived on the island the daughter of a fisherman whose beauty even as a child was extraordinary. As she grew, Cho—for such was her name—improved in looks, and, in spite of her lowly birth, she had the manners and refinement of a lady. At the age of eighteen there was not a young man on the island who was not in love with her. All were eager to seek her hand in marriage; but hardly any dared to ask, even through the medium of a third party, as was usual.

Amongst them was a handsome fisherman of about twenty years whose name was Shinsaku. Being less simple than the rest, and a little more bold, he one day approached Gisuke, O Cho's brother, on the subject. Gisuke could see nothing against his sister marrying Shinsaku; indeed, he rather liked Shinsaku; and their families had always been friends. So he called his sister O Cho down to the beach, where they were sitting, and told her that Shinsaku had proposed for her hand in marriage, and that he thought it an excellent match, of which her mother would have approved had she been alive. He added: 'You must marry soon, you know. You are eighteen, and we want no spinsters on Hatsushima, or girls brought here from the mainland to marry our bachelors.'

'Stay, stay, my dear brother! I do not want all this sermon on spinsterhood,' cried O Cho. 'I have no intention of remaining single, I can tell you; and as for Shinsaku I would rather marry him than any one else—so do not worry yourself further on that account. Settle the day of the happy event.'

Needless to say, young Gisuke was delighted, and so was Shinsaku; and they settled that the marriage should be three days thence.

Soon, when all the fishing-boats had returned to the village, the news spread; and it would be difficult to describe the state of the younger men's feelings. Hitherto every one had hoped to win the pretty O Cho San; all had lived in that happy hope, and rejoiced in the uncertain state of love, which causes such happiness in its early stages. Shinsaku had hitherto been a general favourite. Now the whole of their hopes were dashed to the ground. O Cho was not for any of them. As for Shinsaku, how they suddenly hated him! What was to be done? they asked one another, little thinking of the comical side, or that in any case O Cho could marry only one of them.

No attention was paid to the fish they had caught; their boats were scarcely pulled high enough on the beach for safety; their minds were wholly given to the question how each and every one of them could marry O Cho San. First of all, it was decided to tell Shinsaku that they would prevent his marriage if possible. There were several fights on the quiet beach, which had never before been disturbed by a display of ill-feeling. At last Gisuke, O Cho's brother, consulted with his sister and Shinsaku; and they decided, for the peace of the island, to break off the marriage, O Cho and her lover determining that at all events they would marry no one else.

However, even this great sacrifice had no effect. There were fully thirty men; in fact, the whole of the bachelors wanted to marry O Cho; they fought daily; the whole island was thrown into a discontent. Poor O Cho San! What could she do? Had not she and Shinsaku done enough already in sacrificing happiness for the peace of the island? There was only one more thing she could do, and, being a Japanese girl, she did it. She wrote two letters, one to her brother Gisuke, another to Shinsaku, bidding them farewell. 'The island of Hatsushima has never had trouble until I was born,' she said. 'For three hundred years or more our people, though poor, have lived happily and in peace. Alas! now it is no longer so, on account of me. Farewell! I shall be dead. Tell our people that I have died to bring them back their senses, for they have been foolish about me. Farewell!'

After leaving the two letters where Gisuke slept, O Cho slipped stealthily out of the house (it was a pouring-wet and stormy night and the 10th of June), and cast herself into the sea from some rocks near her cottage, after well loading her sleeves with stones, so that she might rise no more.

Next morning, when Gisuke found the letters, instinctively he knew what must have happened, and rushed from the house to find Shinsaku. Brother and lover read their letters together, and were stricken with grief, as, indeed, was every one else. A search was made, and soon O Cho's straw slippers were found on the point of rocks near her house. Gisuke knew she must have jumped into the sea here, and he and Shinsaku dived down and found her body lying at the bottom. They brought it to the surface, and it was buried just beyond the rocks on which she had last stood.

From that day Shinsaku was unable to sleep at night. The poor fellow was quite distracted. O Cho's letter and straw slippers he placed beside his bed and surrounded them with flowers. His days he spent decorating and weeping over her tomb.

At last one evening Shinsaku resolved to make away with his own body, hoping that his spirit might find O Cho; and he wandered towards her tomb to take a last farewell. As he did so he thought he saw O Cho, and called her aloud three or four times, and then with outstretched arms he rushed delightedly at her. The noise awoke Gisuke, whose house was close to the grave. He came out, and found Shinsaku clasping the stone pillar which was placed at its head.

Shinsaku explained that he had seen the spirit of O Cho, and that he was about to follow her by taking his life; but from this he was dissuaded.

'Do not do that; devote your life, rather, and I will help with you in building a shrine dedicated to Cho. You will join her when you die by nature; but please her spirit here by never marrying another.'

Shinsaku promised. The young men of the place now began to be deeply sorry for Shinsaku. What selfish beasts they had been! they thought. However, they would mend their ways, and spend all their spare time in building a shrine to O Cho San; and this they did. The shrine is called 'The Shrine of O Cho San of Hatsushima,' and a ceremony is held there every 10th of June. Curious to relate, it invariably rains on that day, and the fishermen say that the spirit of O Cho comes in the rain. Hence the song:—

Today is the tenth of June. May the rain fall in torrents!

For I long to see my dearest O Cho San.

Hi, Hi, Ya-re-ko-no-sa! Ya-re-ko-no-sa!

The shrine still stands, I am told.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/atfj/atfj29.htm

January 16, 2012

IN the reign of the Emperor Sanjo began a particularly unlucky time. It was about the year 1013 A. D. when Sanjo came to the throne—the first year of Chowa. Plague broke out. Two years later the Royal Palace was burned down, and a war began with Korea, then known as 'Shiragi.'

In 1016 another fire broke out in the new Palace. A year later the Emperor gave up the throne, owing to blindness and for other causes. He handed over the reins of office to Prince Atsuhara, who was called the Emperor Go Ichijo, and came to the throne in the first year of Kwannin, about 1017 or 1018. The period during which the Emperor Go Ichijo reigned—about twenty years, up to 1036—was one of the worst in Japanese history. There were more wars, more fires, and worse plagues than ever. Things were in disorder generally, and even Kyoto was hardly safe to people of means, owing to the bands of bandits. In 1025 the most appalling outbreak of smallpox came; there was hardly a village or a town in Japan which escaped.

It is at this period that our story begins. Our heroine (if such she may be called) is no less a deity than the goddess of the great mountain of Fuji, which nearly all the world has heard of, or seen depicted. Therefore, if the legend sounds stupid and childish, blame only my way of telling it (simply, as it was told to me), and think of the Great Mountain of Japan, as to which anything should be interesting; moreover, challenge others for a better. I have been able to find none myself.

During the terrible scourge of smallpox there was a village in Suruga Province called Kamiide, which still exists, but is of little importance. It suffered more badly than most other villages. Scarce an inhabitant escaped. A youth of sixteen or seventeen years was much tried. His mother was taken with the disease, and, his father being dead, the responsibility of the household fell on Yosoji—for such was his name.

Yosoji procured all the help he could for his mother, sparing nothing in the way of medicines and attendance; but his mother grew worse day by day, until at last her life was utterly despaired of. Having no other resource left to him, Yosoji resolved to consult a famous fortuneteller and magician, Kamo Yamakiko.

Kamo Yamakiko told Yosoji that there was but one chance that his mother could be cured, and that lay much with his own courage. 'If,' said the fortune-teller, 'you will go to a small brook which flows from the southwestern side of Mount Fuji, and find a small shrine near its source, where Oki-naga-suku-neo (The God of Long Breath) is worshipped, you may be able to cure your mother by bringing her water therefrom to drink. But I warn you that the place is full of dangers from wild beasts and other things, and that you may not return at all or even reach the place.'

Yosoji, in no way discouraged, made his mind up that he would start on the following morning, and, thanking the fortune-teller, went home to prepare for an early start.

At three o'clock next morning he was off.

It was a long and rough walk, one which he had never taken before; but he trudged gaily on, being sound of limb and bent on an errand of deepest concern.

Towards midday Yosoji arrived at a place where three rough paths met, and was sorely puzzled which to take. While he was deliberating the figure of a beautiful girl clad in white came towards him through the forest. At first Yosoji felt inclined to run; but the figure called to him in silvery notes, saying:

'Do not go. I know what you are here for. You are a brave lad and a faithful son. I will be your guide to the stream, and—take my word for it—its waters will cure your mother. Follow me if you will, and have no fear, though the road is bad and dangerous.'

The girl turned, and Yosoji followed in wonderment.

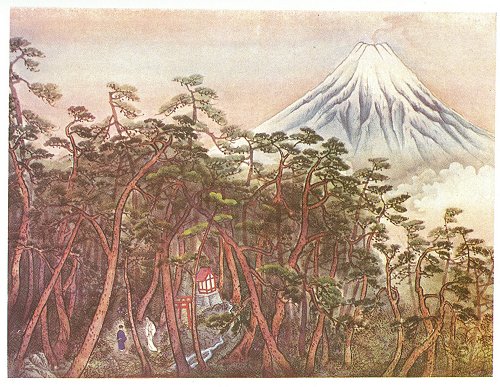

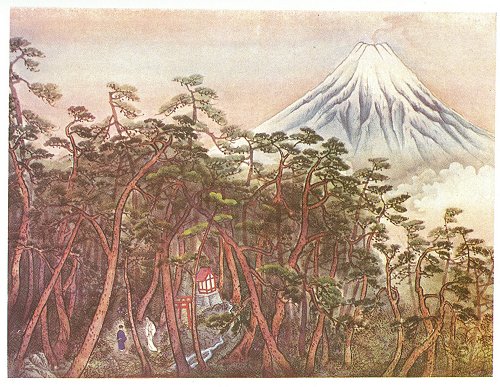

In silence the two went for fully four miles, always upwards and into deeper and more gloomy forests. At last a small shrine was reached, in front of which were two Torii's, and from a cleft of a rock gurgled a silvery stream, the clearness of which was such as Yosoji had never seen before.

'There,' said the white-robed girl, 'is the stream of which you are in search. Fill your gourd, and drink of it yourself, for the waters will prevent you catching the plague. Make haste, for it grows late, and it would not be well for you to be here at night. I shall guide you back to the place where I met you.'

Yosoji did as he was bid, drinking, and then filling the bottle to the brim.

Much faster did they return than they had come, for the way was all downhill. On reaching the meeting of the three paths Yosoji bowed low to his guide, and thanked her for her great kindness; and the girl told him again that it was her pleasure to help so dutiful a son.

'In three days you will want more water for your mother,' said she, 'and I shall be at the same place to be your guide again.'

'May I not ask to whom I am indebted for this great kindness?' asked Yosoji.

'No: you must not ask, for I should not tell you,' answered the girl. Bowing again, Yosoji proceeded on his way as fast as he could, wondering greatly.

On reaching home he found his mother worse. He gave her a cup of the water, and told her of his adventures. During the night Yosoji awoke as usual to attend to his mother's wants, and to give her another bowl of water. Next morning he found that she was decidedly better. During the day he gave her three more doses, and on the morning of the third day he set forth to keep his appointment with the fair lady in white, whom he found seated waiting for him on a rock at the meeting of the three paths.

'Your mother is better I can see from your happy face,' said she. 'Now follow me as before, and make haste. Come again in three days, and I will meet you. It will take five trips in all, for the water must be taken fresh. You may give some to the sick villagers as well.'

Five times did Yosoji take the trip. At the end of the fifth his mother was perfectly well, and must thankful for her restoration; besides which, most of the villagers who had not died were cured. Yosoji was the hero of the hour. Every one marvelled, and wondered who the white-robed girl was; for, though they had heard of the shrine of Oki-naga-suku-neo, none of them knew where it was, and but few would have dared to go if they had known. Of course, all knew that Yosoji was indebted in the first place to the fortune-teller Kamo Yamakiko, to whom the whole village sent presents. Yosoji was not easy in his mind. In spite of the good he had brought about, he thought to himself that he owed the whole of his success in finding and bringing the water to the village to his fair guide, and he did not feel that he had. shown sufficient gratitude. Always he had hurried home as soon as he had got the precious water, bowing his thanks. That was all, and now he felt as if more were due. Surely prayers at the shrine were due, or something; and who was the lady in white? He must find out. Curiosity called upon him to do so. Thus Yosoji resolved to pay one more visit to the spring, and started early in the morning.

Now familiar with the road, he did not stop at the meeting of the three paths, but pursued his way directly to the shrine. It was the first time he had travelled the road alone, and in spite of himself he felt afraid, though he could not say why. Perhaps it was the oppressive gloom of the mysterious dark forest, overshadowed by the holy mountain of Fuji, which in itself was more mysterious still, and filled one both with superstitious and religious feelings and a feeling of awe as well. No one of any imagination can approach the mountain even to-day without having one or all of these emotions.

Yosoji, however, sped on, as fast as he could go, and arrived at the shrine of Oki-naga-suku-neo. He found that the stream had dried up. There was not a drop of water left. Yosoji flung himself upon his knees before the shrine and thanked the God of Long Breath that he had been the means of curing his mother and the surviving villagers. He prayed that his guide to the spring might reveal her presence, and that he might be enabled to meet her once more to thank her for her kindness. When he arose Yosoji saw his guide standing beside him, and bowed low. She was the first to speak.

'You must not come here,' she said. 'I have told you so before. It is a place of great danger for you. Your mother and the villagers are cured. There is no reason for you to come here more.'

'I have come,' answered Yosoji, 'because I have not fully spoken my thanks, and because I wish to tell you how deeply grateful I am to you, as is my mother and as are the whole of our villagers. Moreover, they all as well as I wish to know to whom they are indebted for my guidance to the spring. Though Kamo Yamakiko told me of the spring, I should never have found it but for your kindness, which has now extended over five weeks. Surely you will let us know to whom we are so much indebted, so that we may at least erect a shrine in our temple?'

'All that you ask is unnecessary. I am glad that you are grateful. I knew that one so truly filial as you must be so, and it is because of your filial piety and goodness that I guided you to this health-giving spring, which, as you see, is dry, having at present no further use. It is unnecessary that you should know who I am. We must now part: so farewell. End your life as you have begun it, and you shall be happy.' The beautiful maiden swung a wild camellia branch over her head as if with a beckoning motion, and a cloud came down from the top of the Mount Fuji, enveloping her at first in mist. It then arose, showing her figure to the weeping Yosoji, who now began to realise that he loved the departing figure, and that it was no less a figure than that of the great Goddess of Fujiyama. Yosoji fell on his knees and prayed to her, and the goddess, acknowledging his prayer, threw down the branch of wild camellia.

Yosoji carried it home, and planted it, caring for it with the utmost attention. The branch grew to a tree with marvellous rapidity, being over twenty feet high in two years. A shrine was built; people came to worship the tree; and it is said that the dewdrops from its leaves are a cure for all eye-complaints.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/atfj/atfj33.htm

JAPANESE FOLK TALES ~ YOSOJI'S CAMELLIA TREE

IN the reign of the Emperor Sanjo began a particularly unlucky time. It was about the year 1013 A. D. when Sanjo came to the throne—the first year of Chowa. Plague broke out. Two years later the Royal Palace was burned down, and a war began with Korea, then known as 'Shiragi.'

In 1016 another fire broke out in the new Palace. A year later the Emperor gave up the throne, owing to blindness and for other causes. He handed over the reins of office to Prince Atsuhara, who was called the Emperor Go Ichijo, and came to the throne in the first year of Kwannin, about 1017 or 1018. The period during which the Emperor Go Ichijo reigned—about twenty years, up to 1036—was one of the worst in Japanese history. There were more wars, more fires, and worse plagues than ever. Things were in disorder generally, and even Kyoto was hardly safe to people of means, owing to the bands of bandits. In 1025 the most appalling outbreak of smallpox came; there was hardly a village or a town in Japan which escaped.

It is at this period that our story begins. Our heroine (if such she may be called) is no less a deity than the goddess of the great mountain of Fuji, which nearly all the world has heard of, or seen depicted. Therefore, if the legend sounds stupid and childish, blame only my way of telling it (simply, as it was told to me), and think of the Great Mountain of Japan, as to which anything should be interesting; moreover, challenge others for a better. I have been able to find none myself.

During the terrible scourge of smallpox there was a village in Suruga Province called Kamiide, which still exists, but is of little importance. It suffered more badly than most other villages. Scarce an inhabitant escaped. A youth of sixteen or seventeen years was much tried. His mother was taken with the disease, and, his father being dead, the responsibility of the household fell on Yosoji—for such was his name.

Yosoji procured all the help he could for his mother, sparing nothing in the way of medicines and attendance; but his mother grew worse day by day, until at last her life was utterly despaired of. Having no other resource left to him, Yosoji resolved to consult a famous fortuneteller and magician, Kamo Yamakiko.

Kamo Yamakiko told Yosoji that there was but one chance that his mother could be cured, and that lay much with his own courage. 'If,' said the fortune-teller, 'you will go to a small brook which flows from the southwestern side of Mount Fuji, and find a small shrine near its source, where Oki-naga-suku-neo (The God of Long Breath) is worshipped, you may be able to cure your mother by bringing her water therefrom to drink. But I warn you that the place is full of dangers from wild beasts and other things, and that you may not return at all or even reach the place.'

Yosoji, in no way discouraged, made his mind up that he would start on the following morning, and, thanking the fortune-teller, went home to prepare for an early start.

At three o'clock next morning he was off.

It was a long and rough walk, one which he had never taken before; but he trudged gaily on, being sound of limb and bent on an errand of deepest concern.

Towards midday Yosoji arrived at a place where three rough paths met, and was sorely puzzled which to take. While he was deliberating the figure of a beautiful girl clad in white came towards him through the forest. At first Yosoji felt inclined to run; but the figure called to him in silvery notes, saying:

'Do not go. I know what you are here for. You are a brave lad and a faithful son. I will be your guide to the stream, and—take my word for it—its waters will cure your mother. Follow me if you will, and have no fear, though the road is bad and dangerous.'

The girl turned, and Yosoji followed in wonderment.

In silence the two went for fully four miles, always upwards and into deeper and more gloomy forests. At last a small shrine was reached, in front of which were two Torii's, and from a cleft of a rock gurgled a silvery stream, the clearness of which was such as Yosoji had never seen before.

'There,' said the white-robed girl, 'is the stream of which you are in search. Fill your gourd, and drink of it yourself, for the waters will prevent you catching the plague. Make haste, for it grows late, and it would not be well for you to be here at night. I shall guide you back to the place where I met you.'

Yosoji did as he was bid, drinking, and then filling the bottle to the brim.

Much faster did they return than they had come, for the way was all downhill. On reaching the meeting of the three paths Yosoji bowed low to his guide, and thanked her for her great kindness; and the girl told him again that it was her pleasure to help so dutiful a son.

'In three days you will want more water for your mother,' said she, 'and I shall be at the same place to be your guide again.'

'May I not ask to whom I am indebted for this great kindness?' asked Yosoji.

'No: you must not ask, for I should not tell you,' answered the girl. Bowing again, Yosoji proceeded on his way as fast as he could, wondering greatly.

On reaching home he found his mother worse. He gave her a cup of the water, and told her of his adventures. During the night Yosoji awoke as usual to attend to his mother's wants, and to give her another bowl of water. Next morning he found that she was decidedly better. During the day he gave her three more doses, and on the morning of the third day he set forth to keep his appointment with the fair lady in white, whom he found seated waiting for him on a rock at the meeting of the three paths.

'Your mother is better I can see from your happy face,' said she. 'Now follow me as before, and make haste. Come again in three days, and I will meet you. It will take five trips in all, for the water must be taken fresh. You may give some to the sick villagers as well.'

Five times did Yosoji take the trip. At the end of the fifth his mother was perfectly well, and must thankful for her restoration; besides which, most of the villagers who had not died were cured. Yosoji was the hero of the hour. Every one marvelled, and wondered who the white-robed girl was; for, though they had heard of the shrine of Oki-naga-suku-neo, none of them knew where it was, and but few would have dared to go if they had known. Of course, all knew that Yosoji was indebted in the first place to the fortune-teller Kamo Yamakiko, to whom the whole village sent presents. Yosoji was not easy in his mind. In spite of the good he had brought about, he thought to himself that he owed the whole of his success in finding and bringing the water to the village to his fair guide, and he did not feel that he had. shown sufficient gratitude. Always he had hurried home as soon as he had got the precious water, bowing his thanks. That was all, and now he felt as if more were due. Surely prayers at the shrine were due, or something; and who was the lady in white? He must find out. Curiosity called upon him to do so. Thus Yosoji resolved to pay one more visit to the spring, and started early in the morning.

Now familiar with the road, he did not stop at the meeting of the three paths, but pursued his way directly to the shrine. It was the first time he had travelled the road alone, and in spite of himself he felt afraid, though he could not say why. Perhaps it was the oppressive gloom of the mysterious dark forest, overshadowed by the holy mountain of Fuji, which in itself was more mysterious still, and filled one both with superstitious and religious feelings and a feeling of awe as well. No one of any imagination can approach the mountain even to-day without having one or all of these emotions.

Yosoji, however, sped on, as fast as he could go, and arrived at the shrine of Oki-naga-suku-neo. He found that the stream had dried up. There was not a drop of water left. Yosoji flung himself upon his knees before the shrine and thanked the God of Long Breath that he had been the means of curing his mother and the surviving villagers. He prayed that his guide to the spring might reveal her presence, and that he might be enabled to meet her once more to thank her for her kindness. When he arose Yosoji saw his guide standing beside him, and bowed low. She was the first to speak.

'You must not come here,' she said. 'I have told you so before. It is a place of great danger for you. Your mother and the villagers are cured. There is no reason for you to come here more.'

'I have come,' answered Yosoji, 'because I have not fully spoken my thanks, and because I wish to tell you how deeply grateful I am to you, as is my mother and as are the whole of our villagers. Moreover, they all as well as I wish to know to whom they are indebted for my guidance to the spring. Though Kamo Yamakiko told me of the spring, I should never have found it but for your kindness, which has now extended over five weeks. Surely you will let us know to whom we are so much indebted, so that we may at least erect a shrine in our temple?'

'All that you ask is unnecessary. I am glad that you are grateful. I knew that one so truly filial as you must be so, and it is because of your filial piety and goodness that I guided you to this health-giving spring, which, as you see, is dry, having at present no further use. It is unnecessary that you should know who I am. We must now part: so farewell. End your life as you have begun it, and you shall be happy.' The beautiful maiden swung a wild camellia branch over her head as if with a beckoning motion, and a cloud came down from the top of the Mount Fuji, enveloping her at first in mist. It then arose, showing her figure to the weeping Yosoji, who now began to realise that he loved the departing figure, and that it was no less a figure than that of the great Goddess of Fujiyama. Yosoji fell on his knees and prayed to her, and the goddess, acknowledging his prayer, threw down the branch of wild camellia.

Yosoji carried it home, and planted it, caring for it with the utmost attention. The branch grew to a tree with marvellous rapidity, being over twenty feet high in two years. A shrine was built; people came to worship the tree; and it is said that the dewdrops from its leaves are a cure for all eye-complaints.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/atfj/atfj33.htm

January 9, 2012

In the district called Toichi of Yamato Province, there used to live a goshi named Miyata Akinosuke... [Here I must tell you that in Japanese feudal times there was a privileged class of soldier-farmers,--free-holders,--corresponding to the class of yeomen in England; and these were called goshi.]

In Akinosuke's garden there was a great and ancient cedar-tree, under which he was wont to rest on sultry days. One very warm afternoon he was sitting under this tree with two of his friends, fellow-goshi, chatting and drinking wine, when he felt all of a sudden very drowsy,--so drowsy that he begged his friends to excuse him for taking a nap in their presence. Then he lay down at the foot of the tree, and dreamed this dream:--

He thought that as he was lying there in his garden, he saw a procession, like the train of some great daimyo descending a hill near by, and that he got up to look at it. A very grand procession it proved to be,--more imposing than anything of the kind which he had ever seen before; and it was advancing toward his dwelling. He observed in the van of it a number of young men richly appareled, who were drawing a great lacquered palace-carriage, or gosho-guruma, hung with bright blue silk. When the procession arrived within a short distance of the house it halted; and a richly dressed man--evidently a person of rank--advanced from it, approached Akinosuke, bowed to him profoundly, and then said:--

"Honored Sir, you see before you a kerai [vassal] of the Kokuo of Tokyo. My master, commands me to greet you in his august name, and to place myself wholly at your disposal. He also bids me inform you that he augustly desires your presence at the palace. Be therefore pleased immediately to enter this honorable carriage, which he has sent for your conveyance."

Upon hearing these words Akinosuke wanted to make some fitting reply; but he was too much astonished and embarrassed for speech;--and in the same moment his will seemed to melt away from him, so that he could only do as the kerai bade him. He entered the carriage; the kerai took a place beside him, and made a signal; the drawers, seizing the silken ropes, turned the great vehicle southward;--and the journey began.

In a very short time, to Akinosuke's amazement, the carriage stopped in front of a huge two-storied gateway (romon), of a Chinese style, which he had never before seen. Here the kerai dismounted, saying, "I go to announced the honorable arrival,"--and he disappeared. After some little waiting, Akinosuke saw two noble-looking men, wearing robes of purple silk and high caps of the form indicating lofty rank, come from the gateway. These, after having respectfully saluted him, helped him to descend from the carriage, and led him through the great gate and across a vast garden, to the entrance of a palace whose front appeared to extend, west and east, to a distance of miles. Akinosuke was then shown into a reception-room of wonderful size and splendor. His guides conducted him to the place of honor, and respectfully seated themselves apart; while serving-maids, in costume of ceremony, brought refreshments. When Akinosuke had partaken of the refreshments, the two purple-robed attendants bowed low before him, and addressed him in the following words,--each speaking alternately, according to the etiquette of courts:--

"It is now our honorable duty to inform you... as to the reason of your having been summoned hither... Our master, the King, augustly desires that you become his son-in-law;... and it is his wish and command that you shall wed this very day... the August Princess, his maiden-daughter... We shall soon conduct you to the presence-chamber... where His Augustness even now is waiting to receive you... But it will be necessary that we first invest you... with the appropriate garments of ceremony."

Having thus spoken, the attendants rose together, and proceeded to an alcove containing a great chest of gold lacquer. They opened the chest, and took from it various roes and girdles of rich material, and a kamuri, or regal headdress. With these they attired Akinosuke as befitted a princely bridegroom; and he was then conducted to the presence-room, where he saw the Kokuo of Tokoyo seated upon the daiza, wearing a high black cap of state, and robed in robes of yellow silk. Before the daiza, to left and right, a multitude of dignitaries sat in rank, motionless and splendid as images in a temple; and Akinosuke, advancing into their midst, saluted the king with the triple prostration of usage. The king greeted him with gracious words, and then said:--

"You have already been informed as to the reason of your having been summoned to Our presence. We have decided that you shall become the adopted husband of Our only daughter;--and the wedding ceremony shall now be performed."

As the king finished speaking, a sound of joyful music was heard; and a long train of beautiful court ladies advanced from behind a curtain to conduct Akinosuke to the room in which he bride awaited him.

The room was immense; but it could scarcely contain the multitude of guests assembled to witness the wedding ceremony. All bowed down before Akinosuke as he took his place, facing the King's daughter, on the kneeling-cushion prepared for him. As a maiden of heaven the bride appeared to be; and her robes were beautiful as a summer sky. And the marriage was performed amid great rejoicing.

Afterwards the pair were conducted to a suite of apartments that had been prepared for them in another portion of the palace; and there they received the congratulations of many noble persons, and wedding gifts beyond counting.

Some days later Akinosuke was again summoned to the throne-room. On this occasion he was received even more graciously than before; and the King said to him:--

In the southwestern part of Our dominion there is an island called Raishu. We have now appointed you Governor of that island. You will find the people loyal and docile; but their laws have not yet been brought into proper accord with the laws of Tokyo; and their customs have not been properly regulated. We entrust you with the duty of improving their social condition as far as may be possible; and We desire that you shall rule them with kindness and wisdom. All preparations necessary for your journey to Raishu have already been made."

So Akinosuke and his bride departed from the palace of Tokyo, accompanied to the shore by a great escort of nobles and officials; and they embarked upon a ship of state provided by the king. And with favoring winds they safety sailed to Raishu, and found the good people of that island assembled upon the beach to welcome them.

Akinosuke entered at once upon his new duties; and they did not prove to be hard. During the first three years of his governorship he was occupied chiefly with the framing and the enactment of laws; but he had wise counselors to help him, and he never found the work unpleasant. When it was all finished, he had no active duties to perform, beyond attending the rites and ceremonies ordained by ancient custom. The country was so healthy and so fertile that sickness and want were unknown; and the people were so good that no laws were ever broken. And Akinosuke dwelt and ruled in Raishu for twenty years more,--making in all twenty-three years of sojourn, during which no shadow of sorrow traversed his life.

But in the twenty-fourth year of his governorship, a great misfortune came upon him; for his wife, who had borne him seven children,--five boys and two girls,--fell sick and died. She was buried, with high pomp, on the summit of a beautiful hill in the district of Hanryoko; and a monument, exceedingly splendid, was placed upon her grave. But Akinosuke felt such grief at her death that he no longer cared to live.

Now when the legal period of mourning was over, there came to Raishu, from the Tokoyo palace, a shisha, or royal messenger. The shisha delivered to Akinosuke a message of condolence, and then said to him:--

"These are the words which our august master commands that I repeat to you: 'We will now send you back to your own people and country. As for the seven children, they are the grandsons and granddaughters of the King, and shall be fitly cared for. Do not, therefore, allow you mind to be troubled concerning them.'"

On receiving this mandate, Akinosuke submissively prepared for his departure. When all his affairs had been settled, and the ceremony of bidding farewell to his counselors and trusted officials had been concluded, he was escorted with much honor to the port. There he embarked upon the ship sent for him; and the ship sailed out into the blue sea, under the blue sky; and the shape of the island of Raishu itself turned blue, and then turned grey, and then vanished forever... And Akinosuke suddenly awoke--under the cedar-tree in his own garden!

For a moment he was stupefied and dazed. But he perceived his two friends still seated near him,--drinking and chatting merrily. He stared at them in a bewildered way, and cried aloud,--

"How strange!"

"Akinosuke must have been dreaming," one of them exclaimed, with a laugh. "What did you see, Akinosuke, that was strange?"

Then Akinosuke told his dream,--that dream of three-and-twenty years' sojourn in the realm of Tokyo, in the island of Raishu;--and they were astonished, because he had really slept for no more than a few minutes.

One goshi said:--

"Indeed, you saw strange things. We also saw something strange while you were napping. A little yellow butterfly was fluttering over your face for a moment or two; and we watched it. Then it alighted on the ground beside you, close to the tree; and almost as soon as it alighted there, a big, big ant came out of a hole and seized it and pulling it down into the hole. Just before you woke up, we saw that very butterfly come out of the hole again, and flutter over your face as before. And then it suddenly disappeared: we do not know where it went."

"Perhaps it was Akinosuke's soul," the other goshi said;--"certainly I thought I saw it fly into his mouth... But, even if that butterfly was Akinosuke's soul, the fact would not explain his dream."

"The ants might explain it," returned the first speaker. "Ants are queer beings--possibly goblins... Anyhow, there is a big ant's nest under that cedar-tree."...

"Let us look!" cried Akinosuke, greatly moved by this suggestion. And he went for a spade.

The ground about and beneath the cedar-tree proved to have been excavated, in a most surprising way, by a prodigious colony of ants. The ants had furthermore built inside their excavations; and their tiny constructions of straw, clay, and stems bore an odd resemblance to miniature towns. In the middle of a structure considerably larger than the rest there was a marvelous swarming of small ants around the body of one very big ant, which had yellowish wings and a long black head.

"Why, there is master of my dream!" cried Akinosuke; "and there is the palace of Tokyo!... How extraordinary!... Raishu ought to lie somewhere southwest of it--to the left of that big root... Yes!--here it is!... How very strange! Now I am sure that I can find the mountain of Hanryoko, and the grave of the princess."...

In the wreck of the nest he searched and searched, and at last discovered a tiny mound, on the top of which was fixed a water-worn pebble, in shape resembling a Buddhist monument. Underneath it he found--embedded in clay--the dead body of a female ant.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/kwaidan/kwai15.htm

JAPANESE FOLK TALES ~ THE DREAM OF AKINOSUKE

In the district called Toichi of Yamato Province, there used to live a goshi named Miyata Akinosuke... [Here I must tell you that in Japanese feudal times there was a privileged class of soldier-farmers,--free-holders,--corresponding to the class of yeomen in England; and these were called goshi.]

In Akinosuke's garden there was a great and ancient cedar-tree, under which he was wont to rest on sultry days. One very warm afternoon he was sitting under this tree with two of his friends, fellow-goshi, chatting and drinking wine, when he felt all of a sudden very drowsy,--so drowsy that he begged his friends to excuse him for taking a nap in their presence. Then he lay down at the foot of the tree, and dreamed this dream:--

He thought that as he was lying there in his garden, he saw a procession, like the train of some great daimyo descending a hill near by, and that he got up to look at it. A very grand procession it proved to be,--more imposing than anything of the kind which he had ever seen before; and it was advancing toward his dwelling. He observed in the van of it a number of young men richly appareled, who were drawing a great lacquered palace-carriage, or gosho-guruma, hung with bright blue silk. When the procession arrived within a short distance of the house it halted; and a richly dressed man--evidently a person of rank--advanced from it, approached Akinosuke, bowed to him profoundly, and then said:--

"Honored Sir, you see before you a kerai [vassal] of the Kokuo of Tokyo. My master, commands me to greet you in his august name, and to place myself wholly at your disposal. He also bids me inform you that he augustly desires your presence at the palace. Be therefore pleased immediately to enter this honorable carriage, which he has sent for your conveyance."

Upon hearing these words Akinosuke wanted to make some fitting reply; but he was too much astonished and embarrassed for speech;--and in the same moment his will seemed to melt away from him, so that he could only do as the kerai bade him. He entered the carriage; the kerai took a place beside him, and made a signal; the drawers, seizing the silken ropes, turned the great vehicle southward;--and the journey began.

In a very short time, to Akinosuke's amazement, the carriage stopped in front of a huge two-storied gateway (romon), of a Chinese style, which he had never before seen. Here the kerai dismounted, saying, "I go to announced the honorable arrival,"--and he disappeared. After some little waiting, Akinosuke saw two noble-looking men, wearing robes of purple silk and high caps of the form indicating lofty rank, come from the gateway. These, after having respectfully saluted him, helped him to descend from the carriage, and led him through the great gate and across a vast garden, to the entrance of a palace whose front appeared to extend, west and east, to a distance of miles. Akinosuke was then shown into a reception-room of wonderful size and splendor. His guides conducted him to the place of honor, and respectfully seated themselves apart; while serving-maids, in costume of ceremony, brought refreshments. When Akinosuke had partaken of the refreshments, the two purple-robed attendants bowed low before him, and addressed him in the following words,--each speaking alternately, according to the etiquette of courts:--

"It is now our honorable duty to inform you... as to the reason of your having been summoned hither... Our master, the King, augustly desires that you become his son-in-law;... and it is his wish and command that you shall wed this very day... the August Princess, his maiden-daughter... We shall soon conduct you to the presence-chamber... where His Augustness even now is waiting to receive you... But it will be necessary that we first invest you... with the appropriate garments of ceremony."

Having thus spoken, the attendants rose together, and proceeded to an alcove containing a great chest of gold lacquer. They opened the chest, and took from it various roes and girdles of rich material, and a kamuri, or regal headdress. With these they attired Akinosuke as befitted a princely bridegroom; and he was then conducted to the presence-room, where he saw the Kokuo of Tokoyo seated upon the daiza, wearing a high black cap of state, and robed in robes of yellow silk. Before the daiza, to left and right, a multitude of dignitaries sat in rank, motionless and splendid as images in a temple; and Akinosuke, advancing into their midst, saluted the king with the triple prostration of usage. The king greeted him with gracious words, and then said:--

"You have already been informed as to the reason of your having been summoned to Our presence. We have decided that you shall become the adopted husband of Our only daughter;--and the wedding ceremony shall now be performed."

As the king finished speaking, a sound of joyful music was heard; and a long train of beautiful court ladies advanced from behind a curtain to conduct Akinosuke to the room in which he bride awaited him.

The room was immense; but it could scarcely contain the multitude of guests assembled to witness the wedding ceremony. All bowed down before Akinosuke as he took his place, facing the King's daughter, on the kneeling-cushion prepared for him. As a maiden of heaven the bride appeared to be; and her robes were beautiful as a summer sky. And the marriage was performed amid great rejoicing.

Afterwards the pair were conducted to a suite of apartments that had been prepared for them in another portion of the palace; and there they received the congratulations of many noble persons, and wedding gifts beyond counting.

Some days later Akinosuke was again summoned to the throne-room. On this occasion he was received even more graciously than before; and the King said to him:--

In the southwestern part of Our dominion there is an island called Raishu. We have now appointed you Governor of that island. You will find the people loyal and docile; but their laws have not yet been brought into proper accord with the laws of Tokyo; and their customs have not been properly regulated. We entrust you with the duty of improving their social condition as far as may be possible; and We desire that you shall rule them with kindness and wisdom. All preparations necessary for your journey to Raishu have already been made."

So Akinosuke and his bride departed from the palace of Tokyo, accompanied to the shore by a great escort of nobles and officials; and they embarked upon a ship of state provided by the king. And with favoring winds they safety sailed to Raishu, and found the good people of that island assembled upon the beach to welcome them.

Akinosuke entered at once upon his new duties; and they did not prove to be hard. During the first three years of his governorship he was occupied chiefly with the framing and the enactment of laws; but he had wise counselors to help him, and he never found the work unpleasant. When it was all finished, he had no active duties to perform, beyond attending the rites and ceremonies ordained by ancient custom. The country was so healthy and so fertile that sickness and want were unknown; and the people were so good that no laws were ever broken. And Akinosuke dwelt and ruled in Raishu for twenty years more,--making in all twenty-three years of sojourn, during which no shadow of sorrow traversed his life.

But in the twenty-fourth year of his governorship, a great misfortune came upon him; for his wife, who had borne him seven children,--five boys and two girls,--fell sick and died. She was buried, with high pomp, on the summit of a beautiful hill in the district of Hanryoko; and a monument, exceedingly splendid, was placed upon her grave. But Akinosuke felt such grief at her death that he no longer cared to live.

Now when the legal period of mourning was over, there came to Raishu, from the Tokoyo palace, a shisha, or royal messenger. The shisha delivered to Akinosuke a message of condolence, and then said to him:--

"These are the words which our august master commands that I repeat to you: 'We will now send you back to your own people and country. As for the seven children, they are the grandsons and granddaughters of the King, and shall be fitly cared for. Do not, therefore, allow you mind to be troubled concerning them.'"

On receiving this mandate, Akinosuke submissively prepared for his departure. When all his affairs had been settled, and the ceremony of bidding farewell to his counselors and trusted officials had been concluded, he was escorted with much honor to the port. There he embarked upon the ship sent for him; and the ship sailed out into the blue sea, under the blue sky; and the shape of the island of Raishu itself turned blue, and then turned grey, and then vanished forever... And Akinosuke suddenly awoke--under the cedar-tree in his own garden!

For a moment he was stupefied and dazed. But he perceived his two friends still seated near him,--drinking and chatting merrily. He stared at them in a bewildered way, and cried aloud,--

"How strange!"

"Akinosuke must have been dreaming," one of them exclaimed, with a laugh. "What did you see, Akinosuke, that was strange?"

Then Akinosuke told his dream,--that dream of three-and-twenty years' sojourn in the realm of Tokyo, in the island of Raishu;--and they were astonished, because he had really slept for no more than a few minutes.

One goshi said:--

"Indeed, you saw strange things. We also saw something strange while you were napping. A little yellow butterfly was fluttering over your face for a moment or two; and we watched it. Then it alighted on the ground beside you, close to the tree; and almost as soon as it alighted there, a big, big ant came out of a hole and seized it and pulling it down into the hole. Just before you woke up, we saw that very butterfly come out of the hole again, and flutter over your face as before. And then it suddenly disappeared: we do not know where it went."

"Perhaps it was Akinosuke's soul," the other goshi said;--"certainly I thought I saw it fly into his mouth... But, even if that butterfly was Akinosuke's soul, the fact would not explain his dream."

"The ants might explain it," returned the first speaker. "Ants are queer beings--possibly goblins... Anyhow, there is a big ant's nest under that cedar-tree."...

"Let us look!" cried Akinosuke, greatly moved by this suggestion. And he went for a spade.

The ground about and beneath the cedar-tree proved to have been excavated, in a most surprising way, by a prodigious colony of ants. The ants had furthermore built inside their excavations; and their tiny constructions of straw, clay, and stems bore an odd resemblance to miniature towns. In the middle of a structure considerably larger than the rest there was a marvelous swarming of small ants around the body of one very big ant, which had yellowish wings and a long black head.

"Why, there is master of my dream!" cried Akinosuke; "and there is the palace of Tokyo!... How extraordinary!... Raishu ought to lie somewhere southwest of it--to the left of that big root... Yes!--here it is!... How very strange! Now I am sure that I can find the mountain of Hanryoko, and the grave of the princess."...

In the wreck of the nest he searched and searched, and at last discovered a tiny mound, on the top of which was fixed a water-worn pebble, in shape resembling a Buddhist monument. Underneath it he found--embedded in clay--the dead body of a female ant.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/kwaidan/kwai15.htm

Profile Information

Name: KimikoGender: Female

Hometown: San Francisco

Home country: USA

Current location: California

Member since: Tue Oct 28, 2008, 06:27 PM

Number of posts: 20,776