CFLDem

CFLDem's JournalI find that when I treat people as individuals

as not as members of one classification or another, that it makes the world a much simpler place.

Just my 2 cents...

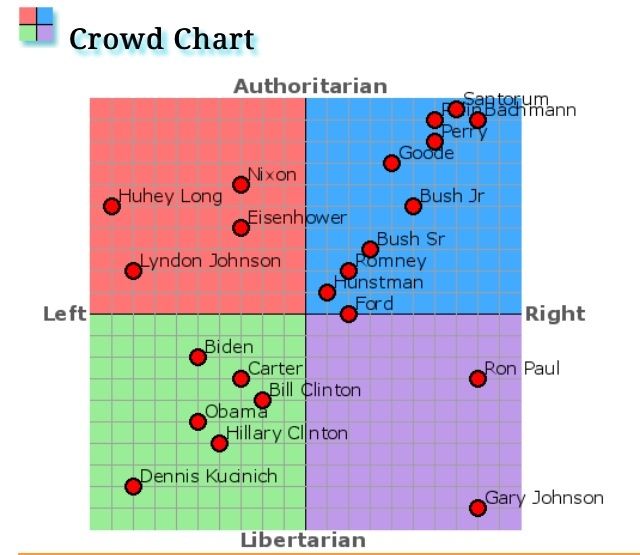

Seeing as it is election season-

I find it good exercise to see where I stand with potential candidates, and in general, here.

[URL= .html][IMG]

.html][IMG] [/IMG][/URL]

[/IMG][/URL]

Where do you stand?

Can Hillary Clinton Count on Women This Time?

by Keli Goff Apr 19, 2014 5:45 am EDT

They famously supported her in 2008—until they helped Obama win Iowa. So will the grandmother-to-be inspire female voters next cycle, or will they judge her on a harsher scale?

The rest here.

Down with patriarchy, and down with extremism

By Brendan McCartney | April 15, 2014

With every major American societal revolution, there have been the conservatives, who advocate for social stability and against assumed “slippery slopes,” and the liberals, who advocate for periodic change and against social stigma. Both conservatives and liberals can be further subdivided into extremists and moderates. During the Civil Rights Movement, for example, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X would both have been considered socially liberal, yet MLK’s nonviolent marches and speeches must have seemed at odds with Malcolm X’s more polarized ideology, which supported violence in the name of progressivism.

In an Ethics seminar a few weeks ago, my classmates and I discussed the necessity of extremism in progressive movements. The class concluded that both moderates and extremists are necessary for societal change, but with a caveat—while extremists help to shake up a relatively stationary social sphere by bringing issues to public light, moderates can make certain perspectives relatable on a more individualized level. Malcolm X’s more extreme platform made enough headlines to raise awareness for the importance of civil rights, but we remember MLK as the humanitarian leader of the Civil Rights Movement.

It is the trend of American society to battle over these social movements on a generational basis. Each few decades, Americans look back on their ancestors and wonder how in the world people used to endorse slavery, segregate schools and keep the vote from women. And each few decades, we grow up with a new social norm that teaches us we are beyond the faults of our ancestors. These days, social issues are often more intangible than slavery, segregation and disenfranchisement. Progressives now fight against conservatives about the subtle detriments of the patriarchy and white privilege, to provide a few examples. Conservatives often respond to these social critiques by denying their very existence.

Read the rest of this excellent article here.

Profile Information

Member since: Sun Oct 27, 2013, 04:35 PMNumber of posts: 2,083

.html][IMG]

.html][IMG] [/IMG][/URL]

[/IMG][/URL]