General Discussion

Related: Editorials & Other Articles, Issue Forums, Alliance Forums, Region ForumsMassacre of Black citizens in East St. Louis, July 2, 1917

Massacre of Black citizens in East St. Louis, tomorrow 1917:

Link to tweet

Previously at DU:

Fri Jul 28, 2017:

east st louis riot race riot (which gave rise to the silent protest parade) (graphic images)

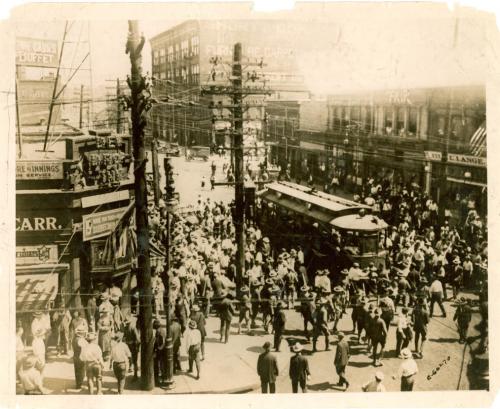

Mob Stopping Street Car, East St. Louis Riot, July 2, 1917

Image Ownership: Public Domain

The city of East St. Louis, Illinois was the scene of one of the bloodiest race riots in the 20th century. Racial tensions began to increase in February, 1917 when 470 African American workers were hired to replace white workers who had gone on strike against the Aluminum Ore Company.

The violence started on May 28th, 1917, shortly after a city council meeting was called. Angry white workers lodged formal complaints against black migrations to the Mayor of East St. Louis. After the meeting had ended, news of an attempted robbery of a white man by an armed black man began to circulate through the city. As a result of this news, white mobs formed and rampaged through downtown, beating all African Americans who were found. The mobs also stopped trolleys and streetcars, pulling black passengers out and beating them on the streets and sidewalks. Illinois Governor Frank O. Lowden eventually called in the National Guard to quell the violence, and the mobs slowly dispersed. The May 28th disturbances were only a prelude to the violence that erupted on July 2, 1917. After the May 28th riots, little was done to prevent any further problems. No precautions were taken to ensure white job security or to grant union recognition. This further increased the already-high level of hostilities towards African Americans. No reforms were made in police force which did little to quell the violence in May. Governor Lowden ordered the National Guard out of the city on June 10th, leaving residents of East St. Louis in an uneasy state of high racial tension.

On July 2, 1917, the violence resumed. Men, women, and children were beaten and shot to death. Around six o’ clock that evening, white mobs began to set fire to the homes of black residents. Residents had to choose between burning alive in their homes, or run out of the burning houses, only to be met by gunfire. In other parts of the city, white mobs began to lynch African Americans against the backdrop of burning buildings. As darkness came and the National Guard returned, the violence began to wane, but did not come to a complete stop.

In response to the rioting, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) sent W.E.B. DuBois and Martha Gruening to investigate the incident. They compiled a report entitled “Massacre at East St. Louis,” which was published in the NAACP’s magazine, The Crisis. The NAACP also staged a silent protest march in New York City in response to the violence. Thousands of well-dressed African Americans marched down Fifth Avenue, showing their concern about the events in East St. Louis.

The Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) also responded to the violence. On July 8th, 1917, the UNIA’s President, Marcus Garvey said “This is a crime against the laws of humanity; it is a crime against the laws of the nation, it is a crime against Nature, and a crime against the God of all mankind.” He also believed that the entire riot was part of a larger conspiracy against African Americans who migrated North in search of a better life: “The whole thing, my friends, is a bloody farce, and that the police and soldiers did nothing to stem the murder thirst of the mob is a conspiracy on the part of the civil authorities to condone the acts of the white mob against Negroes.”

. . . .

http://www.blackpast.org/aah/east-st-louis-race-riot-july-2-1917

{snip}

https://www.google.com/search?q=east+st+louis+riot+1917+images

{snip}

Dennis Donovan

(31,059 posts)bobbieinok

(12,858 posts)Igel

(37,431 posts)I remember being scared when I was 8 and saw the riots in Baltimore. I kept going outside to see if the rioters were coming down our street, once even went a block or two to the main road mark the rioters' progress.

They were confined to a small area 15 miles away, on foot. I was a fool. But, at 8, not having a sense of distance, of course I was a fool.

Take the Tulsa riots and the Greenwood neighborhood. Huge, huge massacre. When I read about it, I imagine an area maybe 20, 30 blocks x 20 or 30 blocks. Then I ask how big Tulsa was at the time and I realize that size of the African-American area I imagined destroyed was far larger than the entirety of Tulsa. The riots/massacre was limited within a 6 x 9 block area--and didn't extend through the entire rectangle that defines. It was mostly in a 3 x 8 block area and stretched down a relatively important street. But you read about it and think of a large city and the scope becomes outsized. We confuse enormity with enormousness.

These things tend to be important, but local.