Honor at last: Former slaves reburied centuries later

Source: Associated Press

Honor at last: Former slaves reburied centuries later

Michael Hill, Associated Press

Updated 3:47 pm, Thursday, May 12, 2016

ALBANY, N.Y. (AP) — Their exhumed bones point to the hard lives of slaves: arthritic backs, missing teeth, muscular frames. In death, they were wrapped in shrouds, buried in pine boxes and — over centuries — forgotten.

Remains of the 14 presumed slaves will soon be reburied near the Hudson River, 11 years after construction workers uncovered the unmarked gravesite. This time, volunteers are honoring the seven adults, five infants and two children in a way that would have been unthinkable when they died. They will be publicly memorialized and buried in personalized boxes beside prominent families in old Albany.

"It's something we agonize over because it's very rare that you have an opportunity to not just speak about the lives of the enslaved, but to actually do something to honor them," said Cordell Reaves, of the Schuyler Flatts Burial Ground Project. "We have an obligation to make sure that these people receive a level of dignity and respect that they never received in life."

. . .

Their headstone is already set. The etching, echoing the style of 18th-century graves, reads: "Here lies the remains of 14 souls known only to God. Enslaved in life, they are slaves no more."

Read more: http://www.chron.com/news/science/article/Honor-at-last-Former-slaves-reburied-centuries-7463533.php

sarge43

(29,173 posts)catnhatnh

(8,976 posts)RIP....

maindawg

(1,151 posts)Right out front.

Bayard

(28,992 posts)That's kind of weird, isn't it?

Judi Lynn

(164,067 posts)New York City Would Really Rather Not Talk About Its Slavery-Loving Past

By Alexander Nazaryan On 4/15/15 at 6:46 AM

November 7, 2005 Issue

It was the summer of 1863, and Abraham Lincoln needed troops. That March, Congress had passed the Enrollment Act, requiring all males between the ages of 20 and 45 to register for a military draft. Since that May, Ulysses S. Grant laid costly siege to the city of Vicksburg, Mississippi, a strategic Confederate fort on the Mississippi River; by June, there would be 80,000 Union soldiers surrounding that city. In late April, “Fighting Joe” Hooker crossed the Rappahannock River, trying to catch Robert E. Lee in a pincer movement. The maneuver failed and the Union lost 17,000 men at the ensuing Battle of Chancellorsville, perhaps Lee’s finest victory. Just two months later, Lee suffered his worst defeat, at Gettysburg. Though victorious there, the Union lost 23,000 men.

The draft began in New York City about two weeks after Gettysburg. The draft would do what all drafts do, which is compel men who do not have the natural constitution of a warrior to become one anyway. You could avoid it by paying $300. Otherwise, you would don the Union blue.

The first day of the draft, Saturday the 11th, went well. The second, Monday the 13th, was a disaster. The Irish had not wanted to work alongside blacks on the docks of Manhattan. They had even less interest in fighting what some called “the nigger war,” so that, presumably, emancipated blacks could come north and take their jobs. Their anger first erupted at the draft offices near today’s United Nations headquarters on the East Side of Manhattan. “The men seemed to be excited beyond expression,” reported The New York Times. The mob “danced with fiendish delight” as it set buildings aflame and attacked blacks, killing dozens.

On the second day, the rioters set upon a four-story house at 339 West 29th Street, in what is today the Manhattan neighborhood of Chelsea. Here, on what was then known as Lamartine Place, stood the graceful home of Quaker abolitionists James Sloan Gibbons and Abigail Hopper Gibbons. It was, according to their friend Joseph H. Choate, “a great resort of abolitionists and extreme anti-slavery people from all parts of the land.” The Hopper-Gibbons house was a known stop on the Underground Railroad, a network of routes and safe houses that, in the first half of the 19th century, whisked runaway slaves across the Mason-Dixon Line. Choate reports that he dined there with William Lloyd Garrison. Present at the dinner was “a jet-black negro who was on his way to freedom.”

More:

http://www.newsweek.com/2015/04/24/new-york-city-would-really-rather-not-talk-about-its-slavery-loving-past-321714.html

[center] ~ ~ ~[/center]

How Slave Labor Made New York

From the Lehman brothers to Tiffany's founder, the city's early titans benefited from toiling blacks.

By: Peter Alan Harper

Posted: Feb. 5 2013 12:50 AM

(The Root) -- The next time some right-wing commentator (Pat Buchanan, are you listening?) bellows about how white people built America, a tour of New York City could be used to point out how the slave trade (i.e., the labor of enslaved Africans) contributed to the creation of this country's financial center.

The very name "Wall Street" is born of slavery, with enslaved Africans building a wall in 1653 to protect Dutch settlers from Indian raids. This walkway and wooden fence, made up of pointed logs and running river to river, later was known as Wall Street, the home of world finance. Enslaved and free Africans were largely responsible for the construction of the early city, first by clearing land, then by building a fort, mills, bridges, stone houses, the first city hall, the docks, the city prison, Dutch and English churches, the city hospital and Fraunces Tavern. At the corner of Wall Street and Broadway, they helped erect Trinity Church.

In 1711 the city's Common Council established a Meal Market at Wall and Water streets for hiring slave labor and auctioning enslaved Africans who disembarked in Manhattan after their arduous trans-Atlantic journey. The merchants used these laborers to operate the port and in such trades as ship carpentry and printing, according to the National Park Service. Africans, according to the Park Service, also engaged in heavy transport, construction work, domestic labor, farming and milling. Their efforts were part of the euphemistically titled Triangular Trade: Africans living on what was then called the Gold Coast -- with Africans being considered black gold -- were bought using New England rum; the Africans were sold in the West Indies to work the fields to create sugar and molasses; and the sugarcane products were taken to New York and New England to be made into rum.

Pier 17 on the East River was a disembarkation point, as were all other slips and docks along lower Manhattan where the Hudson and East rivers rippled by. Today the pier is known as the South Street Seaport, a popular destination for gift-buying tourists who just happen to be visiting where enslaved Africans first touched land in chains.

More:

http://www.theroot.com/articles/culture/2013/02/slavery_in_new_york_wall_street_was_built_with_african_help.html

[center] ~ ~ ~[/center]

The Hidden History of Slavery in New York

Those who believe that slavery in America was strictly a "Southern thing" will discover an eye-opening historical record on display at the New-York Historical Society's current exhibition, "Slavery in New York."

By Adele Oltman

October 24, 2005

In 1991 excavators for a new federal office building in Manhattan unearthed the remains of more than 400 Africans stacked in wooden boxes sixteen to twenty-eight feet below street level. The cemetery dated back to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and its discovery ignited an effort by many Northerners to uncover the history of the institutional complicity with slavery. In 2000 Aetna, one of Connecticut’s largest companies, apologized for profiting from slavery by issuing insurance policies on slaves in the 1850s. After a four-month investigation into its archives, Connecticut’s largest newspaper, the Hartford Courant, apologized for selling advertisement space in its pages for the sale of slaves in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. And in 2004 Ruth Simmons, president of Brown University, established the Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice to investigate “and discuss an uncomfortable piece” of the university’s history: The construction of the university’s first building in 1764, reads a university press release, “involved the labor of Providence area slaves.”

Now another blue-blooded institution–the New-York Historical Society–has joined this important public engagement with our past by mounting an ambitious exhibition, “Slavery in New York.” To all those who think slavery was a “Southern thing,” think again. In 1703, 42 percent of New York’s households had slaves, much more than Philadelphia and Boston combined. Among the colonies’ cities, only Charleston, South Carolina, had more.

The history presented here does not offer the flabby reflection that “slavery is bad” or that once it came to an end everyone lived happily ever after. The Historical Society hired experts led by Richard Rabinowitz, historian and president of the American History Workshop, to untangle the complicated stories of slavery and provide historical context. With more than a score of scholarly advisers weighing in, one wonders whether there were too many cooks, each one bringing a different feature of slavery at the expense of some themes that cry out for explication.

Take, for example, the creation of a distinctive black community of “half-free” New Yorkers in the middle of what is today’s downtown but well north of the cluster of seventeenth-century houses. “Slavery in New York” leaves the designation “half-free” dangling suggestively, unexplored and undefined. Wasn’t slavery straightforward? How could someone be enslaved and free? Fortunately, a book of essays titled Slavery in New York, published in conjunction with the New-York Historical Society, provides a valuable supplement to the exhibit (and a worthwhile resource in its own right). The collection–co-edited by Ira Berlin, a distinguished scholar of slavery, and Leslie M. Harris, the author of a 2003 study of slavery in New York (The Shadow of Slavery)–assembles a prodigious group of scholars, writing on topics ranging from slave rebellion, slavery in the American Revolution, black abolitionism and life after slavery.

Half-free, we learn from Berlin and Harris’s introduction, reflected the evolving nature of slavery in the urban North. The Dutch West India Company that governed New Amsterdam worked its chattel hard, clearing the land, splitting logs, milling lumber and building wharves, roads and fortifications; but slavery was so ill defined in those days that slaves collected wages. In 1635, when wages were not forthcoming, a small group petitioned the company for redress, and that’s when they became “half-free.” As a condition of their half-freedom, families who sustained themselves as farmers agreed to labor for the company when it called on them and pay an annual tribute in furs, produce or wampum. This arrangement provided the company with a loyal reserve force without the responsibility for supporting its workers. It was less beneficial for the half-free men and women. Their status was not automatically passed down to their children, who instead remained the property of the company. This anomalous sorting of humanity produced an ongoing struggle over freedom, and it reflected “the ambiguous place of black men and black women in New Netherland. Exploited, enslaved, unequal to be sure,” write Berlin and Harris, “they were recognized as integral, if inferior, members of the Dutch colony on the Hudson.” And their status conferred on them a penchant to make trouble.

More:

http://www.thenation.com/article/hidden-history-slavery-new-york/

[center]

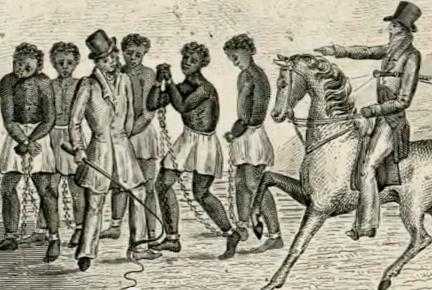

New York Public Library/From ''Slavery in New York''

Slavery was legal in New York until 1827.

ETC., ETC., ETC. [/center]

Bayard

(28,992 posts)Very educational. The picture of the man holding up the baby for auction while the mother cries below is just heartbreaking.

LiberalElite

(14,691 posts)The discovery highlighted the forgotten history of African slaves in colonial and federal New York City, who were integral to its development. By the American Revolutionary War, they constituted nearly a quarter of the population in the city. New York had the second-largest number of slaves in the nation after Charleston, South Carolina. Scholars and African-American civic activists joined to publicize the importance of the site and lobby for its preservation. The site was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1993 and a National Monument in 2006.

In 2003 Congress appropriated funds for a memorial at the site and directed redesign of the federal courthouse to allow for this. A design competition attracted more than 60 proposals for a design. The memorial was dedicated in 2007 to commemorate the role of Africans and African Americans in colonial and federal New York City, and in United States history. Several pieces of public art were also commissioned for the site. A visitor center opened in 2010 to provide interpretation of the site and African-American history in New York.