Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

Editorials & Other Articles

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

The Problems with Facts and Persuasion

A trio of articles on this subject. None are the last word, and you may know of others.

Why People Are So Averse to Facts

Facts about all manner of things have made headlines recently as the Trump administration continues to make statements, reports, and policies at odds with things we know to be true. Whether it’s about the size of his inauguration crowd, patently false and fear-mongering inaccuracies about transgender persons in bathrooms, rates of violent crime in the U.S., or anything else, lately it feels like the facts don’t seem to matter. The inaccuracies and misinformation continue despite the earnest attempts of so many to correct each falsehood after it is made. It’s exhausting. But why is it happening?

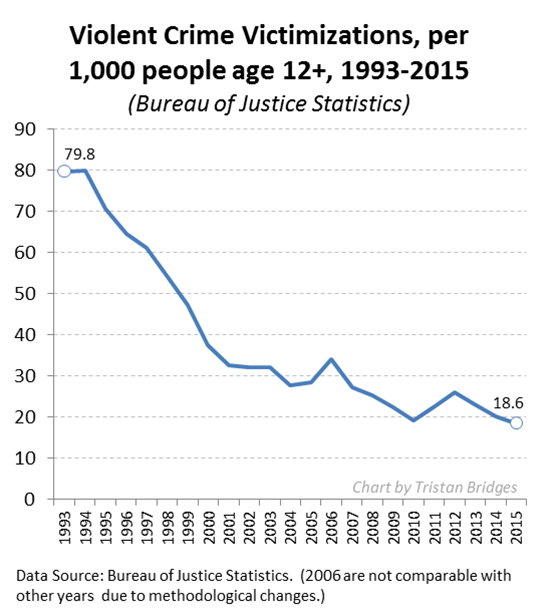

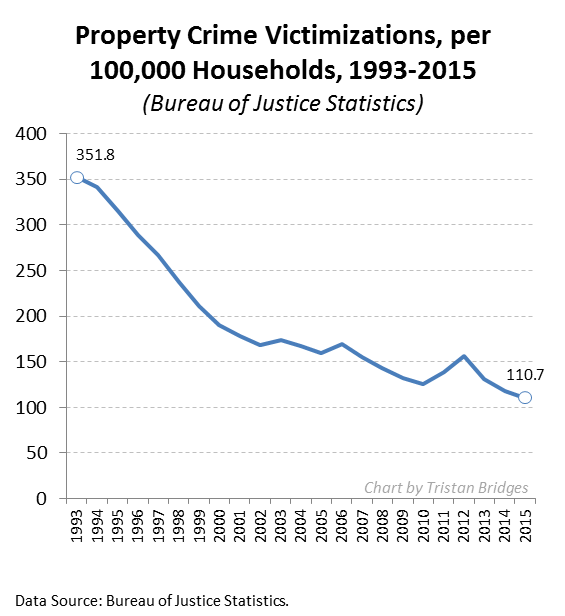

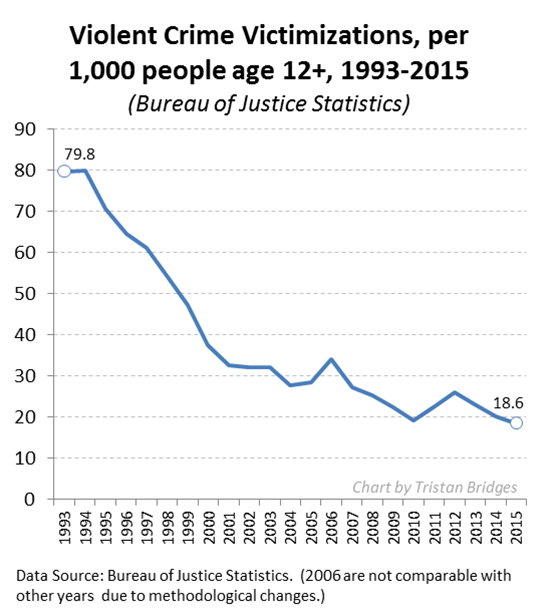

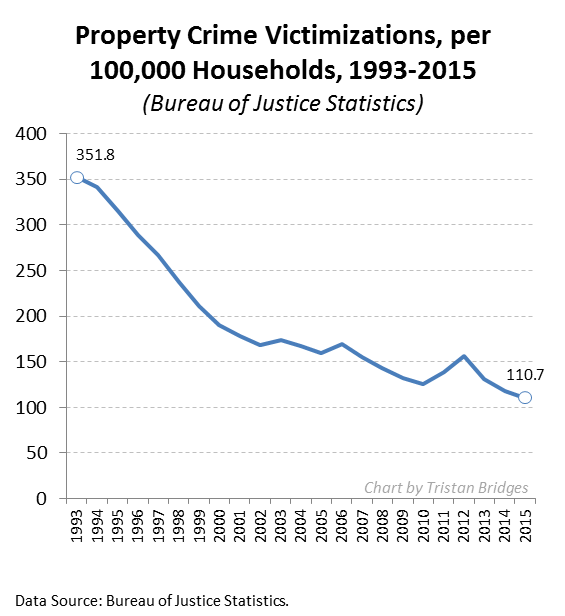

Many of the inaccuracies seem like they ought to be easy enough to challenge as data simply don’t support the statements made. Consider the following charts documenting the violent crime rate and property crime rate in the U.S. over the last quarter century (measured by the Bureau of Justice Statistics). The overall trends are unmistakable: crime in the U.S. has been declining for a quarter of a century.

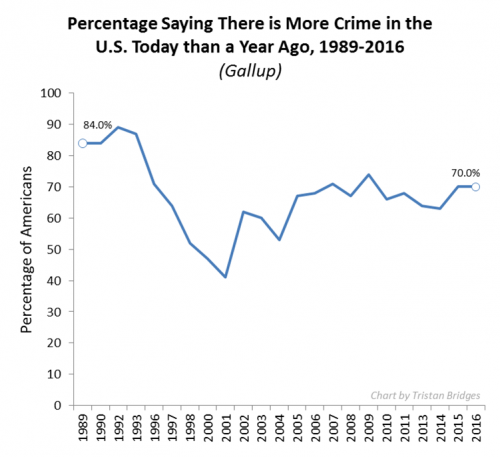

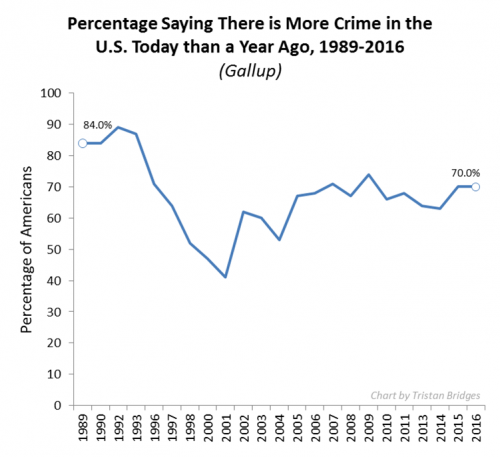

Now compare the crime rate with public perceptions of the crime rate collected by Gallup (below). While the crime rate is going down, the majority of the American public seems to think that crime has been getting worse every year. If crime is going down, why do so many people seem to feel that there is more crime today than there was a year ago? It’s simply not true.

There is more than one reason this is happening. But, one reason I think the alternative facts industry has been so effective has to do with a concept social scientists call the “backfire effect.” As a rule, misinformed people do not change their minds once they have been presented with facts that challenge their beliefs. But, beyond simply not changing their minds when they should, research shows that they are likely to become more attached to their mistaken beliefs. The factual information “backfires.” When people don’t agree with you, research suggests that bringing in facts to support your case might actually make them believe you less. In other words, fighting the ill-informed with facts is like fighting a grease fire with water. It seems like it should work, but it’s actually going to make things worse.

https://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2017/02/27/why-the-american-public-seems-allergic-to-facts/

Facts about all manner of things have made headlines recently as the Trump administration continues to make statements, reports, and policies at odds with things we know to be true. Whether it’s about the size of his inauguration crowd, patently false and fear-mongering inaccuracies about transgender persons in bathrooms, rates of violent crime in the U.S., or anything else, lately it feels like the facts don’t seem to matter. The inaccuracies and misinformation continue despite the earnest attempts of so many to correct each falsehood after it is made. It’s exhausting. But why is it happening?

Many of the inaccuracies seem like they ought to be easy enough to challenge as data simply don’t support the statements made. Consider the following charts documenting the violent crime rate and property crime rate in the U.S. over the last quarter century (measured by the Bureau of Justice Statistics). The overall trends are unmistakable: crime in the U.S. has been declining for a quarter of a century.

Now compare the crime rate with public perceptions of the crime rate collected by Gallup (below). While the crime rate is going down, the majority of the American public seems to think that crime has been getting worse every year. If crime is going down, why do so many people seem to feel that there is more crime today than there was a year ago? It’s simply not true.

There is more than one reason this is happening. But, one reason I think the alternative facts industry has been so effective has to do with a concept social scientists call the “backfire effect.” As a rule, misinformed people do not change their minds once they have been presented with facts that challenge their beliefs. But, beyond simply not changing their minds when they should, research shows that they are likely to become more attached to their mistaken beliefs. The factual information “backfires.” When people don’t agree with you, research suggests that bringing in facts to support your case might actually make them believe you less. In other words, fighting the ill-informed with facts is like fighting a grease fire with water. It seems like it should work, but it’s actually going to make things worse.

https://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2017/02/27/why-the-american-public-seems-allergic-to-facts/

How facts backfire

Researchers discover a surprising threat to democracy: our brains

It’s one of the great assumptions underlying modern democracy that an informed citizenry is preferable to an uninformed one. “Whenever the people are well-informed, they can be trusted with their own government,” Thomas Jefferson wrote in 1789. This notion, carried down through the years, underlies everything from humble political pamphlets to presidential debates to the very notion of a free press. Mankind may be crooked timber, as Kant put it, uniquely susceptible to ignorance and misinformation, but it’s an article of faith that knowledge is the best remedy. If people are furnished with the facts, they will be clearer thinkers and better citizens. If they are ignorant, facts will enlighten them. If they are mistaken, facts will set them straight.

In the end, truth will out. Won’t it?

Maybe not. Recently, a few political scientists have begun to discover a human tendency deeply discouraging to anyone with faith in the power of information. It’s this: Facts don’t necessarily have the power to change our minds. In fact, quite the opposite. In a series of studies in 2005 and 2006, researchers at the University of Michigan found that when misinformed people, particularly political partisans, were exposed to corrected facts in news stories, they rarely changed their minds. In fact, they often became even more strongly set in their beliefs. Facts, they found, were not curing misinformation. Like an underpowered antibiotic, facts could actually make misinformation even stronger.

This bodes ill for a democracy, because most voters — the people making decisions about how the country runs — aren’t blank slates. They already have beliefs, and a set of facts lodged in their minds. The problem is that sometimes the things they think they know are objectively, provably false. And in the presence of the correct information, such people react very, very differently than the merely uninformed. Instead of changing their minds to reflect the correct information, they can entrench themselves even deeper.

http://archive.boston.com/bostonglobe/ideas/articles/2010/07/11/how_facts_backfire/

How to get people to overcome their bias

One of the tricks our mind plays is to highlight evidence which confirms what we already believe. If we hear gossip about a rival we tend to think "I knew he was a nasty piece of work"; if we hear the same about our best friend we're more likely to say "that's just a rumour". If you don't trust the government then a change of policy is evidence of their weakness; if you do trust them the same change of policy can be evidence of their inherent reasonableness.

Once you learn about this mental habit – called confirmation bias – you start seeing it everywhere.

This matters when we want to make better decisions. Confirmation bias is OK as long as we're right, but all too often we’re wrong, and we only pay attention to the deciding evidence when it’s too late.

How we should {try} to protect our decisions from confirmation bias depends on why, psychologically, confirmation bias happens. There are, broadly, two possible accounts and a classic experiment from researchers at Princeton University pits the two against each other, revealing in the process a method for overcoming bias.

http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20170131-why-wont-some-people-listen-to-reason

One of the tricks our mind plays is to highlight evidence which confirms what we already believe. If we hear gossip about a rival we tend to think "I knew he was a nasty piece of work"; if we hear the same about our best friend we're more likely to say "that's just a rumour". If you don't trust the government then a change of policy is evidence of their weakness; if you do trust them the same change of policy can be evidence of their inherent reasonableness.

Once you learn about this mental habit – called confirmation bias – you start seeing it everywhere.

This matters when we want to make better decisions. Confirmation bias is OK as long as we're right, but all too often we’re wrong, and we only pay attention to the deciding evidence when it’s too late.

How we should {try} to protect our decisions from confirmation bias depends on why, psychologically, confirmation bias happens. There are, broadly, two possible accounts and a classic experiment from researchers at Princeton University pits the two against each other, revealing in the process a method for overcoming bias.

http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20170131-why-wont-some-people-listen-to-reason

1 replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

The Problems with Facts and Persuasion (Original Post)

Denzil_DC

Feb 2017

OP

Denzil_DC

(8,978 posts)1. To add a more optimistic note to the mix: another possible approach

Psychological 'vaccine' could help immunize public against 'fake news' on climate change

In medicine, vaccinating against a virus involves exposing a body to a weakened version of the threat, enough to build a tolerance.

Social psychologists believe that a similar logic can be applied to help "inoculate" the public against misinformation, including the damaging influence of 'fake news' websites propagating myths about climate change.

A new study compared reactions to a well-known climate change fact with those to a popular misinformation campaign. When presented consecutively, the false material completely cancelled out the accurate statement in people's minds - opinions ended up back where they started.

Researchers then added a small dose of misinformation to delivery of the climate change fact, by briefly introducing people to distortion tactics used by certain groups. This "inoculation" helped shift and hold opinions closer to the truth - despite the follow-up exposure to 'fake news'.

https://phys.org/news/2017-01-psychological-vaccine-immunize-fake-news.html

In medicine, vaccinating against a virus involves exposing a body to a weakened version of the threat, enough to build a tolerance.

Social psychologists believe that a similar logic can be applied to help "inoculate" the public against misinformation, including the damaging influence of 'fake news' websites propagating myths about climate change.

A new study compared reactions to a well-known climate change fact with those to a popular misinformation campaign. When presented consecutively, the false material completely cancelled out the accurate statement in people's minds - opinions ended up back where they started.

Researchers then added a small dose of misinformation to delivery of the climate change fact, by briefly introducing people to distortion tactics used by certain groups. This "inoculation" helped shift and hold opinions closer to the truth - despite the follow-up exposure to 'fake news'.

https://phys.org/news/2017-01-psychological-vaccine-immunize-fake-news.html