Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

Editorials & Other Articles

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

Who killed the Chrysler Airflow?

Too Good to Succeed

July 23, 2013 | by B. Alexandra Szerlip

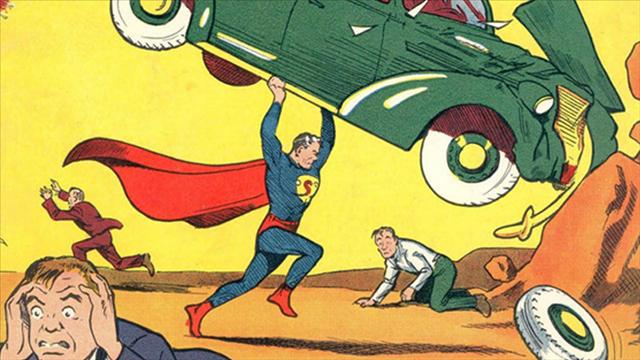

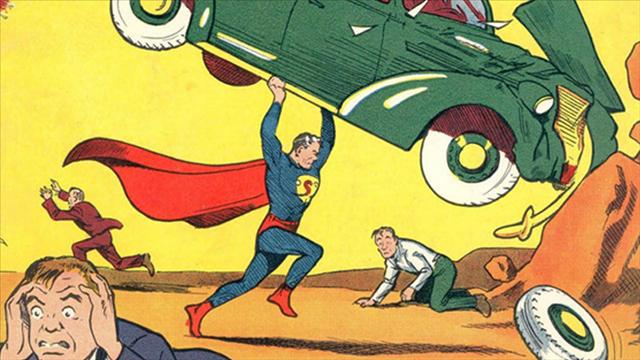

In the summer of 1938, when the first issue of Action Comics introduced the world to Superman, its cover featured the Man of Steel lifting a steel-framed Chrysler Airflow, “the first sincere and authentic streamlined car,”1 above his head. It was the 1937 model, down to its rounded, beetle-brow hood and tapered rear, its grooved speed lines and triangular back “opera” window, its whitewall tires and condensed, newly horizontal grille. The following year, when Universal Pictures decided to make a film version of the popular radio serial The Green Hornet, the screenplay called for the hero to drive a car with “ultramodern lines,” something that looked fast. (“That thing travels faster than the bullets I send after it,” notes a patrol officer during a chase scene.) But by then, the Airflow—a vehicle vastly superior in speed, safety, and comfort to anything on America’s roads—had been so maligned in the public’s imagination, thanks in part to a competitor’s expensive smear campaign, that, decades later, it would still be spoken of as the greatest failure in automotive history. Instead, Universal chose a 1937 Ford Lincoln Zephyr. The name was meant to evoke the Burlington Zephyr, a 1934 streamlined train (featured in the 1935 film The Silver Streak). When The Green Hornet returned as a TV series in 1966, the Black Beauty returned as a Chrysler Imperial, modified to fire rockets as the 200-mph Black Beauty, the Green Hornet’s signature transport, its speedster “look” augmented with stylized lightning bolts painted on the fender skirts and a “Flight of the Bumblebee” soundtrack.

Chrysler’s 1929 coupe had been inspired, claimed company ad men, by “the canons of ancient classic art … authentic forms of beauty which have come down the centuries unsurpassed and unchallenged,” its radiator with cowl molding suggested the repetition motif in a Parthenon frieze, its front elevation replicated the Egyptian lotus leaf pattern. “This patient pursuit of beauty will doubtless prove a revelation to those who have probably accepted Chrysler symmetry and charm as fortunate but more or less accidental.” The following year, the new models were said to be “as distinctive and charming” as the Parisian couture of Paquin and Worth. But the focus soon shifted from ancient history and European aesthetics to what was taking shape in the New World’s own backyard. Walter P. Chrysler was a self-made man who understood the importance of tenacity and vision. In 1905, he had borrowed a considerable amount of money to buy a car that caught his eye for the sole purpose of dismantling it to see how it worked. A few years later, he was General Motors’s first vice president, and not long after that, he quit to start a rival company that was now riding high. In 1933, despite a debilitating economy—wages nationwide had dropped sixty percent, more than twelve million Americans were unemployed, and business as a whole was running at a net loss exceeding five billion dollars—Chrysler turned a considerable profit, the only company to produce more cars that year than it had in its Parthenon-Egyptian Lotus phase, just prior to the crash...

The taillights and dual headlamps were flush to the body, the rear wheels were enclosed; there were chrome-enhanced, wraparound bumpers, a dust-proof luggage compartment, and one no longer had to step up from the running board to get inside. An almost theatrical (what Loewy would call “hysterical”) grille of vertical chrome bars ran up and over the sloped hood. And then there were the white-walled inner-tube tires, a natty touch, like a double pair of gleaming spats. Adding white as “trim” on black was, according to at least one contemporary source, a Bel Geddes innovation.4 The interior featured divan-like adjustable seating. The leather-trimmed cushions set into polished chrome tubular frames created a sophisticated, Moderne armchair look. The flooring was marbleized rubber, the various hard surfaces molded from Bakelite or Formica. It has so many Art Deco touches, notes vintage car collector Jay Leno, that “it looks like you’re sitting in the Chrysler Building.” ...

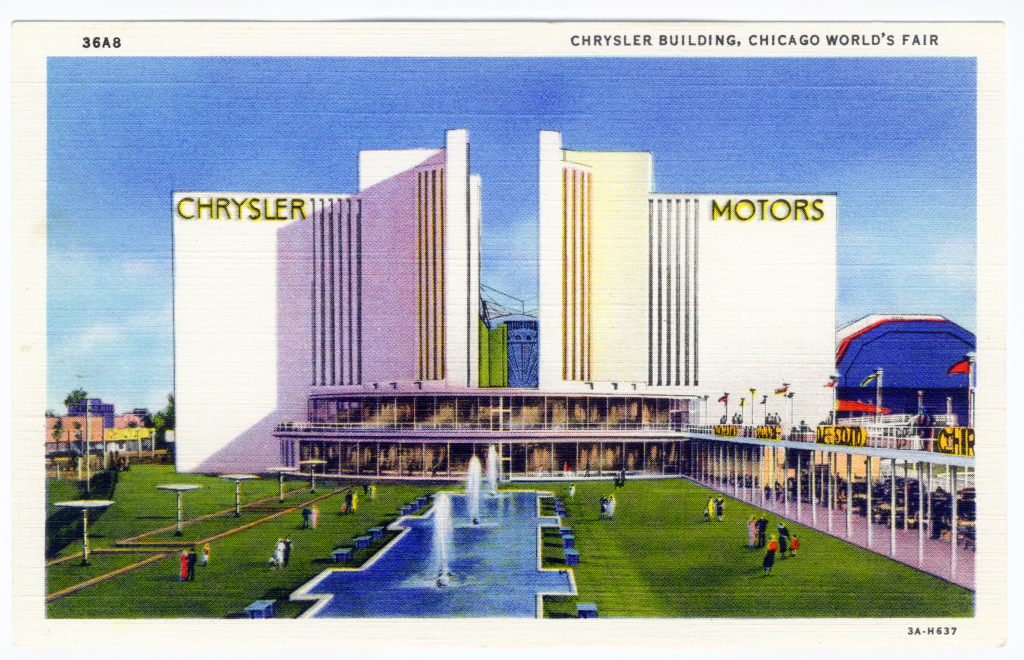

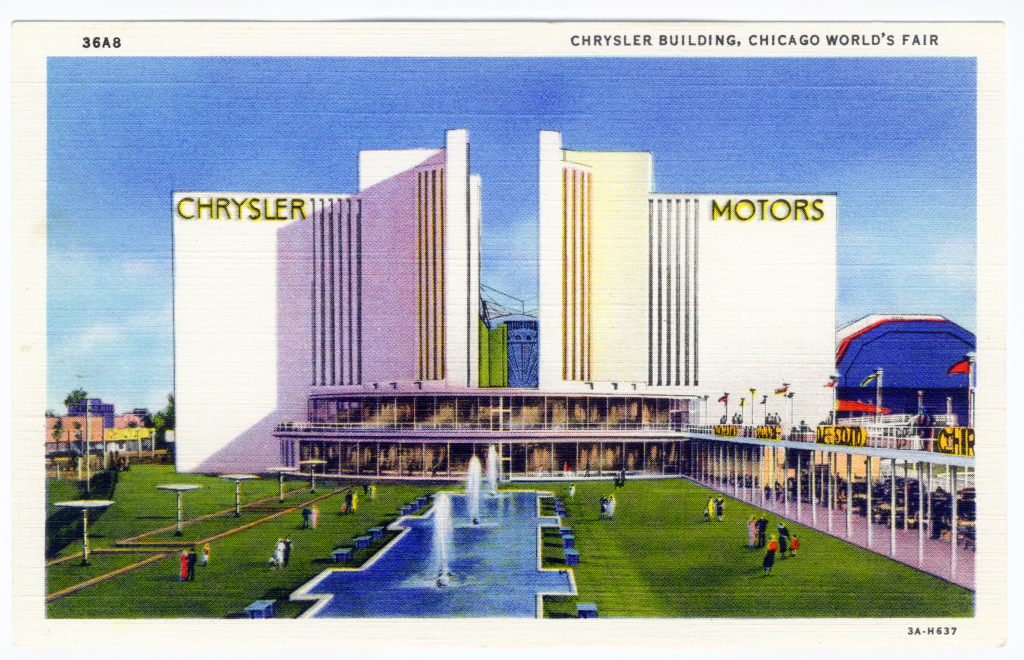

In David Mamet’s 1977 play, The Water Engine, a struggling young Depression-era engineer, Charles Lang, creates an engine that runs on the energy released when the hydrogen and oxygen molecules of H2O are separated. Cheap. Efficient. “Green.” Revolutionary.24 It’s his ticket, Lang thinks, to a better life. At first, the powers-that-be take him for a madman, a crazy dreamer. But when his engine proves itself, they quickly try to buy him off and bury it. When Lang refuses to relinquish the rights (the bad guys include a patent lawyer), both he and his sister meet a gruesome end. It’s difficult to ignore the shadows of the Airflow and the Tucker Torpedo in this cautionary tale. Set against the background of Chicago’s “World of Progress” Fair, where the Airflow had been showcased, it’s a haunting indictment of the American Dream, an evisceration of the Horatio Alger and “level playing field” myths that so many in the twentieth century were raised to believe in. Thirty-five years after Mamet’s play debuted, an MIT professor invented his own “water engine,” an artificial leaf that, when dropped into a jar of water in the sunlight, bubbles away, releasing hydrogen that can be used in fuel cells to make electricity.

http://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2013/07/23/too-good-to-succeed/

July 23, 2013 | by B. Alexandra Szerlip

In the summer of 1938, when the first issue of Action Comics introduced the world to Superman, its cover featured the Man of Steel lifting a steel-framed Chrysler Airflow, “the first sincere and authentic streamlined car,”1 above his head. It was the 1937 model, down to its rounded, beetle-brow hood and tapered rear, its grooved speed lines and triangular back “opera” window, its whitewall tires and condensed, newly horizontal grille. The following year, when Universal Pictures decided to make a film version of the popular radio serial The Green Hornet, the screenplay called for the hero to drive a car with “ultramodern lines,” something that looked fast. (“That thing travels faster than the bullets I send after it,” notes a patrol officer during a chase scene.) But by then, the Airflow—a vehicle vastly superior in speed, safety, and comfort to anything on America’s roads—had been so maligned in the public’s imagination, thanks in part to a competitor’s expensive smear campaign, that, decades later, it would still be spoken of as the greatest failure in automotive history. Instead, Universal chose a 1937 Ford Lincoln Zephyr. The name was meant to evoke the Burlington Zephyr, a 1934 streamlined train (featured in the 1935 film The Silver Streak). When The Green Hornet returned as a TV series in 1966, the Black Beauty returned as a Chrysler Imperial, modified to fire rockets as the 200-mph Black Beauty, the Green Hornet’s signature transport, its speedster “look” augmented with stylized lightning bolts painted on the fender skirts and a “Flight of the Bumblebee” soundtrack.

Chrysler’s 1929 coupe had been inspired, claimed company ad men, by “the canons of ancient classic art … authentic forms of beauty which have come down the centuries unsurpassed and unchallenged,” its radiator with cowl molding suggested the repetition motif in a Parthenon frieze, its front elevation replicated the Egyptian lotus leaf pattern. “This patient pursuit of beauty will doubtless prove a revelation to those who have probably accepted Chrysler symmetry and charm as fortunate but more or less accidental.” The following year, the new models were said to be “as distinctive and charming” as the Parisian couture of Paquin and Worth. But the focus soon shifted from ancient history and European aesthetics to what was taking shape in the New World’s own backyard. Walter P. Chrysler was a self-made man who understood the importance of tenacity and vision. In 1905, he had borrowed a considerable amount of money to buy a car that caught his eye for the sole purpose of dismantling it to see how it worked. A few years later, he was General Motors’s first vice president, and not long after that, he quit to start a rival company that was now riding high. In 1933, despite a debilitating economy—wages nationwide had dropped sixty percent, more than twelve million Americans were unemployed, and business as a whole was running at a net loss exceeding five billion dollars—Chrysler turned a considerable profit, the only company to produce more cars that year than it had in its Parthenon-Egyptian Lotus phase, just prior to the crash...

The taillights and dual headlamps were flush to the body, the rear wheels were enclosed; there were chrome-enhanced, wraparound bumpers, a dust-proof luggage compartment, and one no longer had to step up from the running board to get inside. An almost theatrical (what Loewy would call “hysterical”) grille of vertical chrome bars ran up and over the sloped hood. And then there were the white-walled inner-tube tires, a natty touch, like a double pair of gleaming spats. Adding white as “trim” on black was, according to at least one contemporary source, a Bel Geddes innovation.4 The interior featured divan-like adjustable seating. The leather-trimmed cushions set into polished chrome tubular frames created a sophisticated, Moderne armchair look. The flooring was marbleized rubber, the various hard surfaces molded from Bakelite or Formica. It has so many Art Deco touches, notes vintage car collector Jay Leno, that “it looks like you’re sitting in the Chrysler Building.” ...

In David Mamet’s 1977 play, The Water Engine, a struggling young Depression-era engineer, Charles Lang, creates an engine that runs on the energy released when the hydrogen and oxygen molecules of H2O are separated. Cheap. Efficient. “Green.” Revolutionary.24 It’s his ticket, Lang thinks, to a better life. At first, the powers-that-be take him for a madman, a crazy dreamer. But when his engine proves itself, they quickly try to buy him off and bury it. When Lang refuses to relinquish the rights (the bad guys include a patent lawyer), both he and his sister meet a gruesome end. It’s difficult to ignore the shadows of the Airflow and the Tucker Torpedo in this cautionary tale. Set against the background of Chicago’s “World of Progress” Fair, where the Airflow had been showcased, it’s a haunting indictment of the American Dream, an evisceration of the Horatio Alger and “level playing field” myths that so many in the twentieth century were raised to believe in. Thirty-five years after Mamet’s play debuted, an MIT professor invented his own “water engine,” an artificial leaf that, when dropped into a jar of water in the sunlight, bubbles away, releasing hydrogen that can be used in fuel cells to make electricity.

http://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2013/07/23/too-good-to-succeed/

1 replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

Who killed the Chrysler Airflow? (Original Post)

MinM

Jul 2013

OP

Ah, yes. If you can't succeed, make the other guy fail. Standard business practice.

SharonAnn

Jul 2013

#1

SharonAnn

(14,152 posts)1. Ah, yes. If you can't succeed, make the other guy fail. Standard business practice.