Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

Editorials & Other Articles

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

The DU Lounge

Related: Culture Forums, Support ForumsSpecial diets might boost the power of drugs to vanquish cancers

https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2021/04/special-diets-might-boost-power-drugs-vanquish-cancers

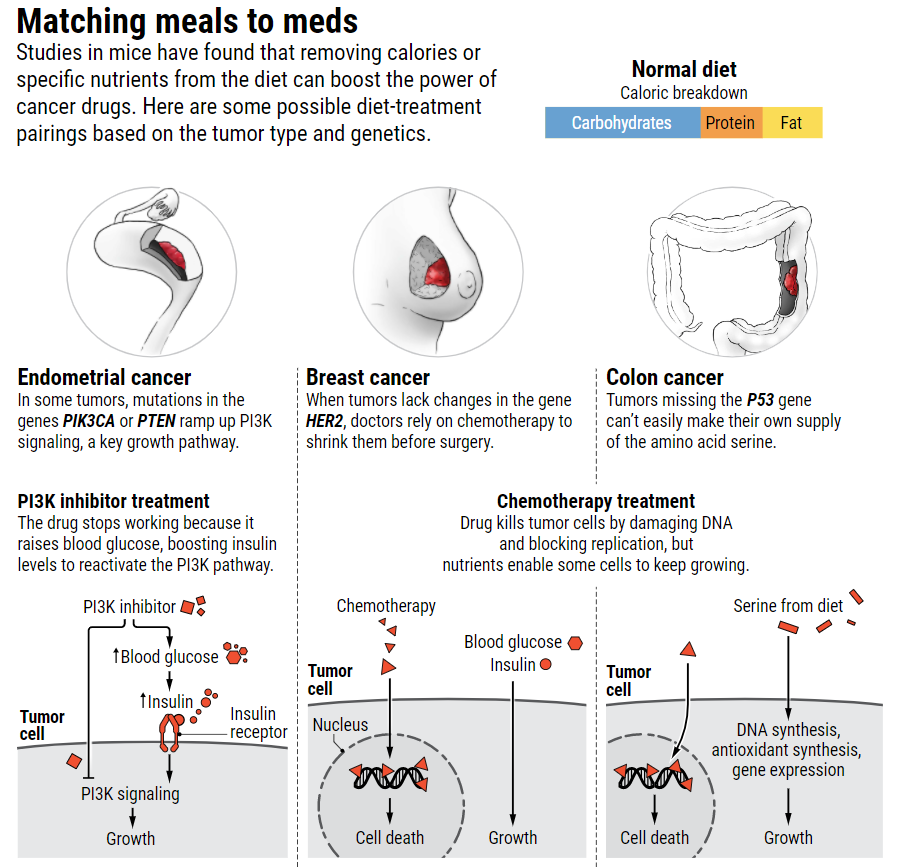

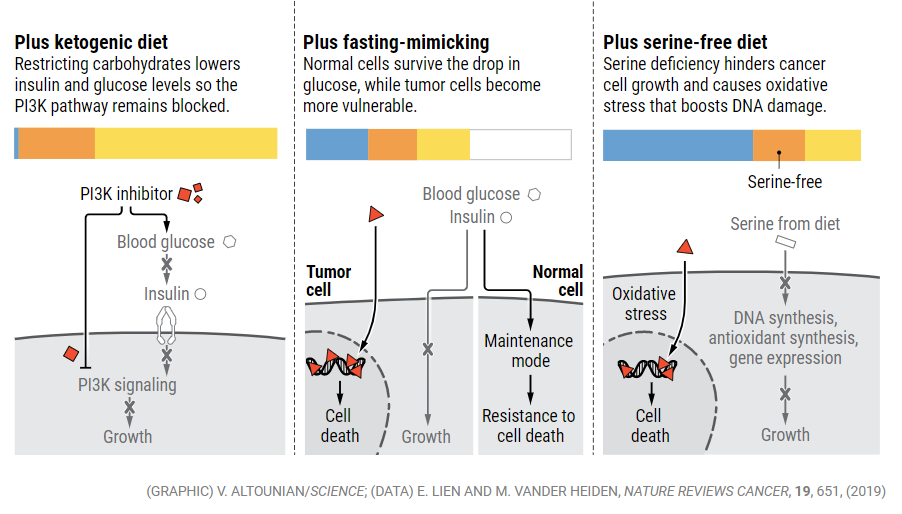

When New York City medical oncologist Vicky Makker meets a patient with endometrial cancer that has spread or recurred, she knows the outlook isn’t good. Even after radiation and drug treatments, most women with advanced disease die within 5 years. But this spring, Makker is helping launch two clinical trials she hopes will change the picture. The drug patients will receive, called a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor, has already failed in multiple cancer trials. But the new studies are taking an unconventional tack to resurrect the drug: putting patients on a ketogenic diet, a low-carbohydrate regimen that typically involves loads of meat, cheese, eggs, and vegetables. The researchers hope the diet will render tumours more vulnerable to the drug, which blocks a growth-promoting pathway in cells. “It’s very outside of the mainstream thinking,” says Makker, a researcher at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. The trials are the brainchild of cell metabolism researcher Lewis Cantley of Weill Cornell Medicine (WCM). Decades ago, he discovered the PI3K signalling pathway, which the drugs aim to target. More recently, his lab showed in mice that a ketogenic diet can counter tumours’ resistance to those drugs.

Cantley isn’t the first to suggest that a particular diet, such as fasting or selectively reducing certain nutrients, can make cancer treatments work better. For at least a century, doctors and self-styled nutrition experts have touted the idea in bestselling books and, more recently, on popular websites. “There’s a big industry there, but it’s not based on a real understanding of what’s going on in a tumour cell,” says cancer biologist Karen Vousden of the Francis Crick Institute in London. Still, some early clinical trials showed hints of an effect. Now, studies from high-profile labs are spawning a new wave of trials with more rigorous underpinnings. Scientists including Vousden, who cofounded a company with Cantley to test diet-drug combinations in cancer trials, are unravelling the molecular pathways by which slashing calories or removing a dietary component can bolster the effects of drugs. In mice with cancer, “the effects are oftentimes on the same order of magnitude as those from the drugs that we give patients. That’s a powerful thing to think about,” says physician-scientist Matthew Vander Heiden of the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. And the idea appeals to patients, he adds. “Diet is something that people feel like they can control.”

STILL, COMPELLING RESULTS in patients will be needed to overcome some oncologists’ view of special diets as fringy alternative medicine. The doubts often focus on a pioneer in the field, biochemist Valter Longo of the University of Southern California and the Italian Foundation for Cancer Research’s Institute of Molecular Oncology, who has built a huge popular following with his fasting research. Critics worry the media attention encourages cancer patients to diet without adequate evidence. Longo agrees patients should not improvise and says fasting needs more clinical testing. His labs in Los Angeles and Milan are full of hungry mice. Longo began his career studying caloric restriction, which can extend the life spans of diverse species and has been shown to reduce the incidence of cancer in rodents and monkeys.

Because few people can stay on low-calorie diets in the long term, Longo shifted his focus to fasting, a treatment offered for various ailments as far back as ancient Greece. In two key papers in 2008 and 2012, his team reported that reducing nutrients in the medium used to grow cells in a dish protected normal cells from the toxic effects of chemotherapy drugs such as cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin, yet made cancer cells more likely to die. In mice with cancer, fasting—drinking only water for 2 or 3 days—helped the drugs curb tumour growth and boosted the animals’ survival. Longo’s explanation is that fasting, which lowers levels of glucose in the blood, causes healthy cells to hunker down in a protective mode. But cancer cells need to keep growing, which puts them at risk of starvation. Fasting also reduces the body’s production of hormones, such as insulin, that can drive tumour growth. Both effects may make the cancer cells more susceptible to chemotherapy.

snip

Nature, Science, and PNAS are the three most prestigious general-science journals, and Nature and Science are among the most influential journals overall in the world.