Latin America

Related: About this forumLocated a long paper containing the confessions of Chile's most notorious torturer under Pinochet.

I'll finish reading it tonight, having started it late this afternoon. It would be very worthwhile to anyone actually looking for real information on what happened in Chile during the US right-wing President Nixon-planned and supported sadistic dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet.

Very glad to see it, having read quotes from it over the years:

Confessing Evil:

A Performative Approach to Perpetrators= Confessions and Chilean Memory Politics

. . .

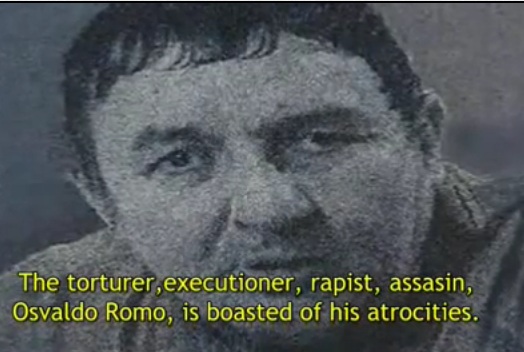

Osvaldo Romo Mena, alias Guatón (Big Fat) Romo, scandalized a Chilean and international

audience with this confession broadcast on the Miami-based cable television station Univisión in 1995.

Romo had served as a civilian member of DINA, General Augusto Pinochet=s secret police, during the

early years of the dictatorship (1973-75). He became well-known as one of the most brutal torturers

within the clandestine torture centers run by DINA.

Scholars have analyzed testimonials by victims of authoritarian state violence, but Romo=s

televised account reflects a new genre: authoritarian state perpetrators= confessions. The lack of

attention to perpetrators= confessions is not entirely surprising. Most perpetrators have remained silent

about their pasts. When they do confess, they tend to repeat the same denials used during the

authoritarian regimes. But increasingly in Latin America and in other parts of the world, perpetrators

have broken the code of silence and told their stories about authoritarian regime violence. Recognizing

the potential value that these confessions could have for Anunca más@ memory politics (or remembering

to not repeat the past), the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) institutionalized a

process by which perpetrators could receive amnesty in exchange for truthful confessions of political

crimes committed during the apartheid era. The TRC has become a model for future truth commissions

around the world, yet no systematic analysis to date explores the political impact of perpetrators=

confessions.2

Latin America, albeit without the unique amnesty arrangement offered in South Africa,

provides insights into the type of confessions that perpetrators make, how different social groups

respond to them, and the meaning of these confessions and the responses to them on political change

and stability.

How do Chileans react, for example, when Romo not only admits to using violence, but glorifies

it, and even appears to have derived pleasure from it? Romo=s account offers a unique study of

perpetrators= confessions. He, like most perpetrators, never apologizes for his past crimes. Indeed, he

does not recognize his acts as wrongdoing at all. His Aconfession@ therefore involves typical strategies

used by perpetrators to diffuse responsibility: remaining silent about some events, denying others,

justifying his acts as part of a Awar@ context, and Aforgetting@ details. What distinguishes Romo=s

confession from all others, however, is the perverse and sadistic pleasure he exudes, both through his

words and body, in harming others.

To analyze the impact of this, and other confessions, discursive analysis proves too limited.

2

What perpetrators say provides only part of the analysis. The unspoken cues that perpetrators use to

describe and explain themselves and their actions proves equally important in shaping political memory.

Moreover, where the confession is made shapes both what is said and how it is interpreted. The

political context in which the confession is made further influences the content of the text and responses

to it. How individuals and groups respond to the confession, moreover, influence its political impact.

Observers rarely passively watch perpetrators= confessions. Instead, they become active participants in

generating political meaning from them. This project, therefore, involves a performative analysis that

considers the interaction of timing, staging, acting, perpetrators= confessional scripts, and audience

responses to produce political meaning.

In particular, this project analyzes the impact of Romo=s confession on Anunca más@ memory

politics in Chile. It questions whether perpetrators= confessions alone B particularly the type made by

Romo B can have a positive impact on four components of that memory project: truth,

acknowledgment, justice, and collective memory. Certainly perpetrators= confessions have the potential

to provide new truths about the past. They could determine the location of the disappeared or explain

the cause of death. These confessions could, moreover, acknowledge, or confirm victims= accounts, by

accounting for the past violence and condemning it. Perpetrators= accounts could establish the facts

necessary to investigate, prosecute, and bring justice for past crimes. They could also advance

restorative and symbolic forms of justice through truth, acknowledgment, and acts of contrition. By

having perpetrators from within the repressive apparatus admit to its atrocities, confessions can advance

Acollective memory,@ or a common national understanding of human rights violations and a commitment

to avoid repeating them. How could anyone deny the violence of the past when those from within the

repressive apparatus admit to it?

On their own, perpetrators= confessions do not achieve these lofty goals. Sometimes they may

even work against them by hiding the truth, resurrecting the authoritarian regime=s denials and

justifications that blame, rather than acknowledge, victims for past violence, and escaping justice through

amnesty laws. Romo=s text represents one of those confessions that would have a negative impact on

memory politics. But by analyzing the interactions within the entire performance, this sadistic confession

provides a more realistic notion of how and when perpetrators confessions can positively influence

memory politics.

More:

http://lasa.international.pitt.edu/lasa2003/payneleigh.pdf

Osvaldo Romo

Image of the body of Romo being taken to its grave after he died in prison:

Insults flying from people regarding this burial. Can be translated in google translate for Spanish English:

https://translate.google.com/

Very refreshing hearing their opinions of this event, considering the circumstances:

Link to tweet

Judi Lynn

(164,078 posts)Wikipedia:

Human rights violations in Pinochet's Chile

Human rights violations in Pinochet's Chile were the crimes against humanity, persecution of opponents, political repression and state terrorism committed by the Chilean Armed Forces, members of Carabineros de Chile and civil repressive agents members of a secret police, during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet in Chile from September 11, 1973, until March 11, 1990.

According to the Commission of Truth and Reconciliation (Rettig Commission) and the National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture (Valech Commission), the number of direct victims of human rights violations in Chile accounts for around 30,000 people: 27,255 tortured and 2,279 executed. In addition, some 200,000 people suffered exile and an unknown number went through clandestine centers and illegal detention.[citation needed]

The systematic human rights violations that were committed by the military government of Chile, under General Augusto Pinochet, included gruesome acts of physical and sexual abuse, as well as psychological damage. From 11 September 1973 to 11 March 1990, Chilean armed forces, the police and all those aligned with the military junta were involved in institutionalizing fear and terror in Chile.[1]

The most prevalent forms of state-sponsored torture that Chilean prisoners endured were electric shocks, waterboarding, beatings, and sexual abuse. Another common mechanism of torture employed was "disappearing" those who were deemed to be potentially subversive because they adhered to leftist political doctrines. The tactic of "disappearing" the enemies of the Pinochet regime was systematically carried out during the first four years of military rule. The "disappeared" were held in secret, subjected to torture and were often never seen again. Both the National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture (Valech Report) and the Commission of Truth and Reconciliation (Rettig Report) approximate that there were around 30,000 victims of human rights abuses in Chile, with 27,255 tortured[2] and 2,279 executed.[3]

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_rights_violations_in_Pinochet%27s_Chile