Women's Rights & Issues

Related: About this forumPolice Officer Domestic Violence Is A Crisis. It's Time for States to Take Action. (trigger warning)

(And the MISOGYNIST, PATRIARCHAL, CHRISTOFASCIST, THEOCRATIC, WAR ON WOMEN continues apace)

Police Officer Domestic Violence Is A Crisis. It’s Time for States to Take Action. (trigger warning)

PUBLISHED 12/11/2025 by Brian Stanley

Elevated rates of intimate partner violence in police families, paired with weak oversight and harmful policies, make officer-abusers a uniquely urgent public safety threat.

Police tape is shown at the scene in Brampton, Ontario, on December 9, 2025, of a shooting that happens the previous evening in the parking lot of the Shoppers World mall in the Hurontario St. and Steeles area. Peel Regional Police say shots are fired into a vehicle with a lone occupant, killing a 25-year-old Brampton man. (Photo by Mike Campbell/NurPhoto via Getty Images)Studies and reviews show intimate partner violence in law enforcement families is elevated. (Mike Campbell / NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Domestic violence by police officers is a nationwide scourge. While the actual number of cases that happen every year is unknown, it’s likely in the tens of thousands. Police officers in almost every state have been charged with domestic violence since the start of 2025. Such figures demonstrate that police officer domestic violence is a structural failure, not the isolated misconduct of ‘a few bad apples.’ These numbers become even more sobering in light of police officer-abusers’ training and responsibilities, which makes them uniquely dangerous, and extremely undertrained: On average, less than 2 percent of police academy training time is spent on domestic violence response, while 17 percent is spent on weapons and defensive training. And when there’s smoke, there’s fire. Law enforcement, and the criminal-legal system more broadly, are notoriously bad at supporting domestic violence survivors. Many law enforcement organizations resisted abuser gun bans since their inception, despite ample evidence that owning a firearm increases domestic violence abuse risk. Similarly, the first “modern” domestic violence laws didn’t come into play until the mid-1970s, and the first rules about police officer domestic violence didn’t surface until the 1990s, though it’s unclear if they’ve been implemented or followed.

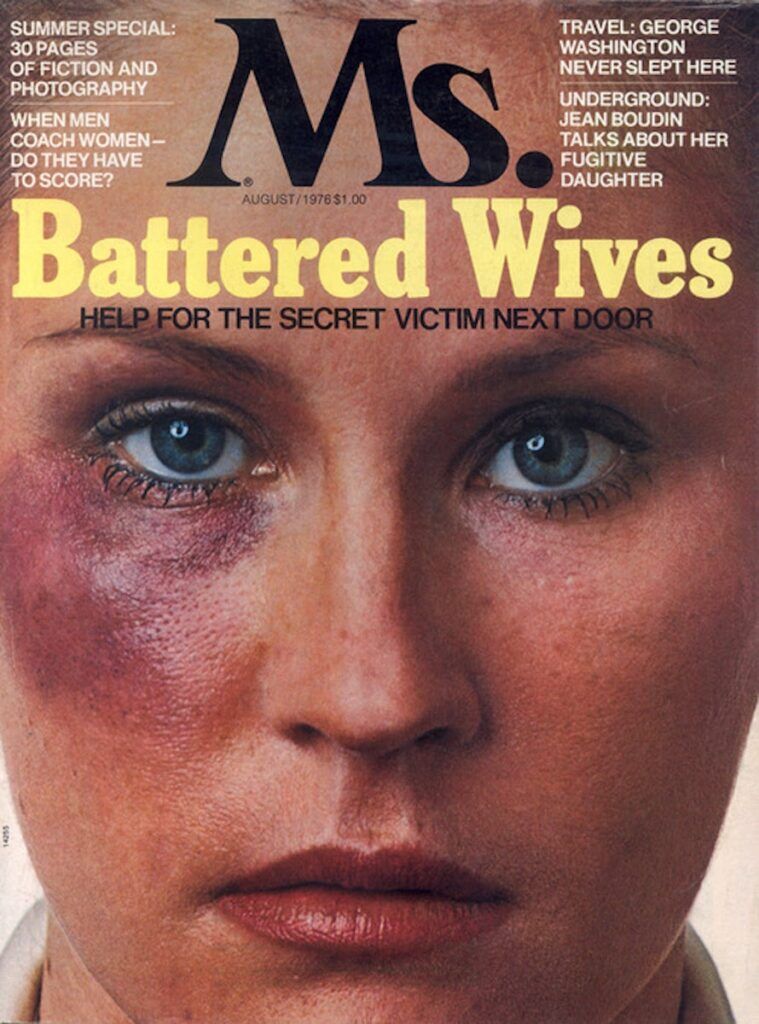

“Violence begins in the home,” wrote Gloria Steinem in the August 1976 issue of Ms., “and it must end there.”

Case and point can be found in Newark, N.J., where the Newark Police Department, who has a police domestic violence policy, was just recently released from an oversight measure implemented by the Department of Justice nearly 10 years ago. Despite a decade of monitoring and reforms, the final report about the oversight decree noted that “domestic violence by [Newark Police Department] officers remains a serious concern.” Why is it that oversight can be lifted while abuse remains in the ranks? As one practitioner notes, maybe it’s because “law enforcement’s response to domestic violence in their own family reveals their genuine attitudes and beliefs about domestic violence in any family.”

Given these circumstances, it’s time for states to take action to protect survivors and change the broken systems that have for too long let this violence go on. Addressing this crisis is particularly challenging given the nature of police officer domestic violence. Officer-abusers often have close ties to fellow police, district attorneys and first responders—all of the people involved with responding to and prosecuting domestic violence calls. Alongside access to firearms, they also have insider knowledge of how domestic violence cases are investigated and where domestic violence shelters are located. And they have training in authority and control tactics used to subdue people during an arrest, which further imperils victims. For decades, the response to domestic violence writ large has been criminalization: Punish the abuser to prevent the crime. Currently, this looks like public policy dominated by laws and funding that address domestic violence with intervention from the criminal-legal system rather than directly supporting victim needs. When it comes to police officer domestic violence, the downsides of this approach are easy to see. As a loved one of a woman murdered by her officer-abuser spouse told reporters, “Who was she supposed to call for help? When things go sideways, you call 911. He was 911.”

. . . . .

For one, redirecting resources away from criminalization through law enforcement and courts toward programs designed to address the root causes and consequences of domestic violence is an excellent first step. This will look different from community to community, but is usually rooted in anti-poverty, health promotion, gender-based violence prevention, mutual aid and safe, private batterer-intervention programs. We also need more, and better, research on police domestic violence. The first and last time U.S. scholars talked to survivors of police domestic violence was the early 1990s, and those studies gave the highest-ever rates of police domestic violence. (Forty percent of survivors in those studies reported their partner violently losing control within the last year.) Since then, *********researchers have only talked to officer-abusers and their colleagues—not to survivors themselves.********* Every level of government can help change this by funding both the researchers who collect information on the topic and domestic violence care services for victims. In 2023, 40 percent of calls to the National Domestic Violence Hotline went unanswered due to staff and funding shortages, and domestic violence shelters constantly face funding cuts. If practitioners want to get involved, this is a great space to start. Officer-abusers and their victims make clear that something is deeply wrong in our domestic violence support system. For now, we don’t understand the depth of that dysfunction, but we can be certain that more funding, better policy and less criminalization will help drive a better future.

https://msmagazine.com/2025/12/11/police-officer-domestic-violence-women/