Religion

Related: About this forumThe myth of religious violence

The popular belief that religion is the cause of the world’s bloodiest conflicts is central to our modern conviction that faith and politics should never mix. But the messy history of their separation suggests it was never so simple

Illustration by Sam Hofman and Kyle Bean

Karen Armstrong

Thursday 25 September 2014 01.00 EDT

As we watch the fighters of the Islamic State (Isis) rampaging through the Middle East, tearing apart the modern nation-states of Syria and Iraq created by departing European colonialists, it may be difficult to believe we are living in the 21st century. The sight of throngs of terrified refugees and the savage and indiscriminate violence is all too reminiscent of barbarian tribes sweeping away the Roman empire, or the Mongol hordes of Genghis Khan cutting a swath through China, Anatolia, Russia and eastern Europe, devastating entire cities and massacring their inhabitants. Only the wearily familiar pictures of bombs falling yet again on Middle Eastern cities and towns – this time dropped by the United States and a few Arab allies – and the gloomy predictions that this may become another Vietnam, remind us that this is indeed a very modern war.

The ferocious cruelty of these jihadist fighters, quoting the Qur’an as they behead their hapless victims, raises another distinctly modern concern: the connection between religion and violence. The atrocities of Isis would seem to prove that Sam Harris, one of the loudest voices of the “New Atheism”, was right to claim that “most Muslims are utterly deranged by their religious faith”, and to conclude that “religion itself produces a perverse solidarity that we must find some way to undercut”. Many will agree with Richard Dawkins, who wrote in The God Delusion that “only religious faith is a strong enough force to motivate such utter madness in otherwise sane and decent people”. Even those who find these statements too extreme may still believe, instinctively, that there is a violent essence inherent in religion, which inevitably radicalises any conflict – because once combatants are convinced that God is on their side, compromise becomes impossible and cruelty knows no bounds.

Despite the valiant attempts by Barack Obama and David Cameron to insist that the lawless violence of Isis has nothing to do with Islam, many will disagree. They may also feel exasperated. In the west, we learned from bitter experience that the fanatical bigotry which religion seems always to unleash can only be contained by the creation of a liberal state that separates politics and religion. Never again, we believed, would these intolerant passions be allowed to intrude on political life. But why, oh why, have Muslims found it impossible to arrive at this logical solution to their current problems? Why do they cling with perverse obstinacy to the obviously bad idea of theocracy? Why, in short, have they been unable to enter the modern world? The answer must surely lie in their primitive and atavistic religion.

But perhaps we should ask, instead, how it came about that we in the west developed our view of religion as a purely private pursuit, essentially separate from all other human activities, and especially distinct from politics. After all, warfare and violence have always been a feature of political life, and yet we alone drew the conclusion that separating the church from the state was a prerequisite for peace. Secularism has become so natural to us that we assume it emerged organically, as a necessary condition of any society’s progress into modernity. Yet it was in fact a distinct creation, which arose as a result of a peculiar concatenation of historical circumstances; we may be mistaken to assume that it would evolve in the same fashion in every culture in every part of the world.

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/sep/25/-sp-karen-armstrong-religious-violence-myth-secular

djean111

(14,255 posts)unblock

(56,082 posts)religion comes in to unite and embolden one side and to demonize the other, and also to disguise the real motives for war.

let's plunder their land and take their unfair share of resources so that we can distribute it unfairly ourselves is hardly the sort of rallying cry that convinces kids to lay down their lives.

on the other hand, if everyone is content in terms of economics and power, how many people would fight solely to convert?

finally, plenty of wars have happened when religion had little to nothing to do with it. purely economics and power. that's why i think religion really is just how people rationalize and sell wars.

ZombieHorde

(29,047 posts)ISIS how to be properly religious and what really motivates them, then people are correct when they tell anyone how to be properly religious and what really motivates them. The atheist view of how Christians should conduct themselves and what really motivates a Christian is perfectly correct.

Personally, I don't blame religion, I blame obedience for perceived atrocities. Some of this obedience is based upon religion, some is based upon patriotism, some is based upon duty, etc. The peacemakers, such as MLK and Gandhi, were disobedient. They were criminals. Rosa Parks disobeyed. Churches that feed the homeless in parks are disobedient. This is because the constructs of law and order are based upon violence. They are constructed to benefit the few on the backs of the many.

rug

(82,333 posts)Therefore, this statement is incorrect.

I daresay there are as many people who declare themselves atheist that believe religion motivates a particular violence as there are not.

In any event, once you go beyond the simple statement of nonbelief, it is human beings with their own experiences and biases speaking, not atheists per se.

ZombieHorde

(29,047 posts)"...an atheist's/anti-theist's view...", as in one person. I agree atheists hold many different opinions on religion, so my example was too broad, and therefore fallacious. My comment was made within the context of some of the heated atheist/theist debates on this board, but my comment didn't reflect that context, so you had no real reason to assume what I was thinking when I wrote that post.

In my opinion, I have no logical standing for telling you how your relationship with your religion should look like. Likewise, I don't believe anyone has the logical standing for telling members of ISIS what their relationship with their religion should look like.

I hope that makes my claim more clear, even if you still disagree with it.

rug

(82,333 posts)And I still disagree! ![]()

Leontius

(2,270 posts)rest of the human race.

ZombieHorde

(29,047 posts)but I have heard/read people claim that they are not practicing Islam correctly. If I remember correctly, President Obama made a similar claim.

AtheistCrusader

(33,982 posts)Victim of it.

And on the flipside, I have yet to hear someone say they are going to kick my ass because they don't believe in god.

rug

(82,333 posts)There are many more logical reasons than that.

Kicking ass is only a physical manifestation of obnoxious behavior.

AtheistCrusader

(33,982 posts)rug

(82,333 posts)So, I'll just leave my original reply.

AtheistCrusader

(33,982 posts)And how that behavior is learned/propagated.

Jim__

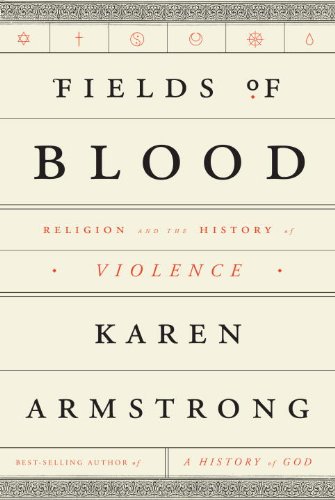

(15,134 posts)As I was reading the article, I was hoping this would be her next book.

[center] [/center]

[/center]

From its description on Amazon:

While many historians have looked at violence in connection with particular religious manifestations (jihad in Islam or Christianity’s Crusades), Armstrong looks at each faith—not only Christianity and Islam, but also Buddhism, Hinduism, Confucianism, Daoism, and Judaism—in its totality over time. As she describes, each arose in an agrarian society with plenty powerful landowners brutalizing peasants while also warring among themselves over land, then the only real source of wealth. In this world, religion was not the discrete and personal matter it would become for us but rather something that permeated all aspects of society. And so it was that agrarian aggression, and the warrior ethos it begot, became bound up with observances of the sacred.

In each tradition, however, a counterbalance to the warrior code also developed. Around sages, prophets, and mystics there grew up communities protesting the injustice and bloodshed endemic to agrarian society, the violence to which religion had become heir. And so by the time the great confessional faiths came of age, all understood themselves as ultimately devoted to peace, equality, and reconciliation, whatever the acts of violence perpetrated in their name.

Industrialization and modernity have ushered in an epoch of spectacular and unexampled violence, although, as Armstrong explains, relatively little of it can be ascribed directly to religion. Nevertheless, she shows us how and in what measure religions, in their relative maturity, came to absorb modern belligerence—and what hope there might be for peace among believers of different creeds in our time.

At a moment of rising geopolitical chaos, the imperative of mutual understanding between nations and faith communities has never been more urgent, the dangers of action based on misunderstanding never greater. Informed by Armstrong’s sweeping erudition and personal commitment to the promotion of compassion, Fields of Blood makes vividly clear that religion is not the problem.