Dennis Donovan

Dennis Donovan's Journal100 Years Ago Today; Terror and Tragedy in Tulsa

The Tulsa race riot (or the Tulsa race massacre) of 1921 took place on May 31 and June 1, 1921, when mobs of whites attacked black residents and businesses of the Greenwood District in Tulsa, Oklahoma. This is considered one of the worst incidents of racial violence in the history of the United States. The attack, carried out on the ground and by air, destroyed more than 35 blocks of the district, at the time the wealthiest black community in the United States.

More than 800 people were admitted to hospitals and more than 6,000 black residents were arrested and detained, many for several days. The Oklahoma Bureau of Vital Statistics officially recorded 36 dead, but the American Red Cross declined to provide an estimate. When a state commission re-examined events in 2001, its report estimated that 100-300 African Americans were killed in the rioting.

The riot began over Memorial Day weekend after 19-year-old Dick Rowland, a black shoeshiner, was accused of assaulting Sarah Page, the 17-year-old white elevator operator of the nearby Drexel Building. He was taken into custody. A subsequent gathering of angry local whites outside the courthouse where Rowland was being held, and the spread of rumours he had been lynched, alarmed the local black population, some of whom arrived at the courthouse armed. Shots were fired and twelve people were killed; ten white and two black. As news of these deaths spread throughout the city, mob violence exploded. Thousands of whites rampaged through the black neighborhood that night and the next day, killing men and women, burning and looting stores and homes. About 10,000 black people were left homeless, and property damage amounted to more than $1.5 million in real estate and $750,000 in personal property ($32 million in 2019).

Many survivors left Tulsa. Black and white residents who stayed in the city were silent for decades about the terror, violence, and losses of this event. The riot was largely omitted from local, state, as well as national, histories: "The Tulsa race riot of 1921 was rarely mentioned in history books, classrooms or even in private. Blacks and whites alike grew into middle age unaware of what had taken place."

In 1996, seventy-five years after the riot, a bi-partisan group in the state legislature authorized formation of the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 (renamed to Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Massacre in November 2018). Members were appointed to investigate events, interview survivors, hear testimony from the public, and prepare a report of events. There was an effort toward public education about these events through the process. The Commission's final report, published in 2001, said that the city had conspired with the mob of white citizens against black citizens; it recommended a program of reparations to survivors and their descendants. The state passed legislation to establish some scholarships for descendants of survivors, encourage economic development of Greenwood, and develop a memorial park in Tulsa to the riot victims. The park was dedicated in 2010.

Monday, May 30, 1921 – Memorial Day

Encounter in the elevator

It is alleged that at some time about or after 4 PM, 19-year-old Dick Rowland, a black shoeshiner employed at a Main Street shine parlor, entered the only elevator of the nearby Drexel Building at 319 South Main Street to use the top-floor restroom, which was restricted to black people. He encountered Sarah Page, the 17-year-old white elevator operator on duty. The two likely knew each other at least by sight, as this building was the only one nearby with a restroom to which Rowland had express permission to use, and the elevator operated by Page was the only one in the building. A clerk at Renberg's, a clothing store on the first floor of the Drexel, heard what sounded like a woman's scream and saw a young black man rushing from the building. The clerk went to the elevator and found Page in what he said was a distraught state. Thinking she had been assaulted, he summoned the authorities.

The 2001 Oklahoma Commission Final Report notes that it was unusual for both Rowland and Page to be working downtown on Memorial Day, when most stores and businesses were closed. It suggests that Rowland had a simple accident, such as tripping and steadying himself against the girl, or perhaps they were lovers and had a quarrel.

Whether – and to what extent – Dick Rowland and Sarah Page knew each other has long been a matter of speculation. It seems reasonable that they would have least been able to recognize each other on sight, as Rowland would have regularly ridden in Page's elevator on his way to and from the restroom. Others, however, have speculated that the pair might have been lovers – a dangerous and potentially deadly taboo, but not an impossibility. Whether they knew each other or not, it is clear that both Dick Rowland and Sarah Page were downtown on Monday, May 30, 1921 – although this, too, is cloaked in some mystery. On Memorial Day, most – but not all – stores and businesses in Tulsa were closed. Yet, both Rowland and Page were apparently working that day.

Yet in the days and years that followed, many who knew Dick Rowland agreed on one thing: that he would never have been capable of rape.

The word "rape" was rarely used in newspapers or academia in the early 20th century. Instead, "assault" was used to describe such an attack.

Brief investigation

Although the police likely questioned Page, no written account of her statement has been found. It is generally accepted that the police determined what happened between the two teenagers was something less than an assault. The authorities conducted a low-key investigation rather than launching a man-hunt for her alleged assailant. Afterward, Page told the police that she would not press charges.

Regardless of whether assault had occurred, Rowland had reason to be fearful. At the time, such an accusation alone put him at risk for attack by white people. Realizing the gravity of the situation, Rowland fled to his mother's house in the Greenwood neighborhood.

Identity of the black rioters

The Morning Tulsa Daily World reported on the 3rd of June, major points of their interview with Deputy Sheriff Barney Cleaver concerning the events leading up to the Tulsa riot. Cleaver was deputy sheriff for Okmulgee county and not under the supervision of the city police department; his duties mainly involved enforcing law among the "coloured people" of Greenwood but he also operated a business as a private investigator. He had previously been dismissed as an investigator for the city police for assisting county officers with a drug raid at Gurley's Hotel but not reporting his involvement to his superiors. He had considerable land holdings and suffered tremendous financial damages as a result of the riot. Among his holdings were several residential properties and Cleaver Hall, a large community gathering place and function hall. He reported personally evicting a number of armed criminals who had taken to barricading themselves within properties he owned. Upon eviction, they merely moved to Cleaver Hall. Cleaver reported that the majority of violence started at Cleaver Hall along with the rioters barricaded inside.Charles Page offered to build him a new home.

The Morning Tulsa Daily World stated, "Cleaver named Will Robinson, a dope peddler and all around bad negro, as the leader of the armed blacks. He has also the names of three others who were in the armed gang at the court house. The rest of the negroes participating in the fight, he says, were former servicemen who had an exaggerated idea of their own importance... They did not belong here, had no regular employment and were simply a floating element with seemingly no ambition in life but to forment trouble." O. W. Gurley, owner of Gurley's Hotel identified the following men by name as arming themselves and gathering in his hotel: Will Robinson, Peg Leg Taylor, Bud Bassett, Henry Van Dyke, Chester Ross, Jake Mayes, O. B. Mann, John Suplesox, Fatty, Jack Scott, Lee Mable, John Bowman and W. S. Weaver.

Tuesday, May 31, 1921

Suspect arrested

One of the sensationalist news articles that contributed to tensions in Tulsa

On the morning after the incident, Detective Henry Carmichael and Henry C. Pack, a black patrolman, located Rowland on Greenwood Avenue and detained him. Pack was one of two black officers on the city's police force, which then included about 45 officers. Rowland was initially taken to the Tulsa city jail at First and Main. Late that day, Police Commissioner J. M. Adkison said he had received an anonymous telephone call threatening Rowland's life. He ordered Rowland transferred to the more secure jail on the top floor of the Tulsa County Courthouse.

Rowland was well known among attorneys and other legal professionals within the city, many of whom knew Rowland through his work as a shoeshiner. Some witnesses later recounted hearing several attorneys defend Rowland in their conversations with one another. One of the men said, "Why, I know that boy, and have known him a good while. That's not in him."

Newspaper coverage

The Tulsa Tribune, one of two white-owned papers published in Tulsa, broke the story in that afternoon's edition with the headline: "Nab Negro for Attacking Girl In an Elevator", describing the alleged incident. According to some witnesses, the same edition of the Tribune included an editorial warning of a potential lynching of Rowland, entitled "To Lynch Negro Tonight". The paper was known at the time to have a "sensationalist" style of news writing. All original copies of that issue of the paper have apparently been destroyed, and the relevant page is missing from the microfilm copy, so the exact content of the column (and whether it existed at all) remains in dispute.

Stand-off at the courthouse

The afternoon edition of the Tribune hit the streets shortly after 3 p.m., and soon news spread of a potential lynching. By 4 pm, local authorities were on alert. White people began congregating at and near the Tulsa County Courthouse. By sunset at 7:34 pm, the several hundred white people assembled outside the courthouse appeared to have the makings of a lynch mob. Willard M. McCullough, the newly elected sheriff of Tulsa County, was determined to avoid events such as the 1920 lynching of white murder suspect Roy Belton in Tulsa, which had occurred during the term of his predecessor. The sheriff took steps to ensure the safety of Rowland. McCullough organized his deputies into a defensive formation around Rowland, who was terrified. One of Scott Ellsworth's references in the 2001 commission report, The Guthrie Daily Leader, reported that Rowland had been taken to the county jail before crowds started to gather. The sheriff positioned six of his men, armed with rifles and shotguns, on the roof of the courthouse. He disabled the building's elevator, and had his remaining men barricade themselves at the top of the stairs with orders to shoot any intruders on sight. The sheriff went outside and tried to talk the crowd into going home, but to no avail. According to an account by Scott Ellsworth, the sheriff was "hooted down".

About 8:20 pm, three white men entered the courthouse, demanding that Rowland be turned over to them. Although vastly outnumbered by the growing crowd out on the street, Sheriff McCullough turned the men away.

A few blocks away on Greenwood Avenue, members of the black community and known criminals associated with underground gambling houses, gathered to discuss the situation at Gurley's Hotel. Given the recent lynching of Belton, a white man accused of murder, they believed that Rowland was greatly at risk. Many black residents were determined to prevent the crowd from lynching Rowland, but they were divided about tactics. Young World War I veterans prepared for a battle by collecting guns and ammunition. Older, more prosperous men feared a destructive confrontation that likely would cost them dearly. O. W. Gurley gave a sworn statement to the Grand Jury that he tried to convince the men that there would be no lynching but that they had responded that Sheriff McCullough had personally told them that their presence was required. About 9:30 pm, a group of approximately 50-60 black men, armed with rifles and shotguns, arrived at the jail to support the sheriff and his deputies to defend Rowland from the mob. Corroborated by ten witnesses, attorney James Luther submitted to the grand jury that they were following the orders of Sheriff McCullough who publicly denied he gave any orders:

"I saw a car full of negroes driving through the streets with guns; I saw Bill McCullough and told him those negroes would cause trouble; McCullough tried to talk to them, and they got out and stood in single file. W. G. Daggs was killed near Boulder and Sixth street. I was under the impression that a man with authority could have stopped and disarmed them. I saw Chief of Police on south side of court house on top step, talking; I did not see any officer except the Chief; I walked in the court house and met McCullough in about 15 feet of his door; I told him these negroes were going to make trouble, and he said he had told them to go home; he went out and told the whites to go home, and one said "they said you told them to come up here." McCullough said "I did not" and a negro said you did tell us to come."

Taking up arms

Having seen the armed black people, some of the more than 1,000 white people at the courthouse went home for their own guns. Others headed for the National Guard armory at Sixth Street and Norfolk Avenue, where they planned to arm themselves. The armory contained a supply of small arms and ammunition. Major James Bell of the 180th Infantry had already learned of the mounting situation downtown and the possibility of a break-in, and he took measures to prevent the same. He called the commanders of the three National Guard units in Tulsa, who ordered all the Guard members to put on their uniforms and report quickly to the armory. When a group of white people arrived and began pulling at the grating over a window, Bell went outside to confront the crowd of 300 to 400 men. Bell told them that the Guard members inside were armed and prepared to shoot anyone who tried to enter. After this show of force, the crowd withdrew from the armory.

At the courthouse, the crowd had swollen to nearly 2,000, many of them now armed. Several local leaders, including Reverend Charles W. Kerr, pastor of the First Presbyterian Church, tried to dissuade mob action. The chief of police, John A. Gustafson, later claimed that he tried to talk the crowd into going home.

Anxiety on Greenwood Avenue was rising. Many blacks worried about the safety of Rowland. Small groups of armed black men ventured toward the courthouse in automobiles, partly for reconnaissance, and to demonstrate they were prepared to take necessary action to protect Rowland.

Many white men interpreted these actions as a "Negro uprising" and became concerned. Eyewitnesses reported gunshots, presumably fired into the air, increasing in frequency during the evening.

Second offer

In Greenwood, rumors began to fly – in particular, a report that white men and women were storming the courthouse. Shortly after 10 pm, a second, larger group of approximately 75 armed black men decided to go to the courthouse. They offered their support to the sheriff, who declined their help. According to witnesses, a white man is alleged to have told one of the armed black men to surrender his pistol. The man refused, and a shot was fired. That first shot may have been accidental, or meant as a warning; it was a catalyst for an exchange of gunfire.

Riot

The gunshots triggered an almost immediate response by the white men, many of whom fired on the black people, who then fired back at the white people. The first "battle" was said to last a few seconds or so, but took a toll, as ten white people and two black people lay dead or dying in the street. The black contingent retreated toward Greenwood. A rolling gunfight ensued. The armed white mob pursued the armed black mob toward Greenwood, with many stopping to loot local stores for additional weapons and ammunition. Along the way, bystanders, many of whom were leaving a movie theater after a show, were caught off guard by the mobs and fled. Panic set in as the white mob began firing on any black people in the crowd. The white mob also shot and killed at least one white man in the confusion.

At around 11 pm, members of the Oklahoma National Guard unit began to assemble at the armory to organize a plan to subdue the rioters. Several groups were deployed downtown to set up guard at the courthouse, police station, and other public facilities. Members of the local chapter of the American Legion joined in on patrols of the streets. The forces appeared to have been deployed to protect the white districts adjacent to Greenwood. The National Guard rounded up numerous black people and took them to the Convention Hall on Brady Street for detention.

Many prominent white Tulsans also participated in the riot[citation needed], including Tulsa founder and KKK member W. Tate Brady, who participated in the riot as a night watchman. It was reported, in This Land Press that W. Tate Brady participated and led the tarring and feathering of a group of men. The article states that police, "delivered the convicted men into the custody of the black-robed Knights of Liberty." The provided document attached to the article states,""I believe the circumstantial evidence is sufficient to prevent any of them from wanting to give anyone any trouble in the way of lawsuits...all made the same statement with emphasis that Tate Brady put on the tar and feathers in the 'name of the women and children of Belgium.' The same is true as to the part that Chief of Police Ed Lucas took. Not all the witnesses said they would swear in court as to...[document incomplete]" The since uncovered remainder of the document continues, "It is a question as to what extent I could go in establishing beyond a doubt the persons in the mob since their disguise with the robes and masks was complete. I doubt if I could do it in a court in Oklahoma at this time." In the Tulsa Daily World article about the incident, the victims were reported to be suspected German spies, referred to as I.W.W.'s. Harlows Weekly also explains the contemporary connection between Belgium, the I.W.W. and the Knights of Liberty. The article sympathetically explains the actions as economically and politically motivated rather than racially motivated. A Kansas detective reported over 200 members of the I.W.W. and their affiliates migrated to Oklahoma to organise an open rebellion among the working class against the war effort planned for November 1, 1917. It was reported that police beat the I.W.W. members before delivering them to the Knights of Liberty. The Tulsa Daily World reported that none of the policemen could identify any of the hooded men. The Tulsa Daily World article states that the policemen were kidnapped, forced to drive the prisoners to a ravine and forced to watch the entire ordeal at gunpoint. Previous reports regarding Brady's character seem favourable and he hired black employees in his businesses. Brady married a Cherokee woman and fought for Cherokee claims against the U.S. government.

At around midnight, white rioters again assembled outside the courthouse. It was a smaller group but more organised and determined. They shouted in support of a lynching. When they attempted to storm the building, the sheriff and his deputies turned them away and dispersed them.

Wednesday, June 1, 1921

Throughout the early morning hours, groups of armed white and black people squared off in gunfights. At this point the fighting was concentrated along sections of the Frisco tracks, a dividing line between the black and white commercial districts. A rumor circulated that more black people were coming by train from Muskogee to help with an invasion of Tulsa. At one point, passengers on an incoming train were forced to take cover on the floor of the train cars, as they had arrived in the midst of crossfire, with the train taking hits on both sides.

Small groups of white people made brief forays by car into Greenwood, indiscriminately firing into businesses and residences. They often received return fire. Meanwhile, white rioters threw lighted oil rags into several buildings along Archer Street, igniting them.

Fires begin

Fires burning along Archer and Greenwood during the Tulsa race riot of 1921

At around 1 am, the white mob began setting fires, mainly in businesses on commercial Archer Street at the southern edge of the Greenwood district. As crews from the Tulsa Fire Department arrived to put out fires, they were turned away at gunpoint. Scott Elsworth makes the same claim, but his reference makes no mention of firefighters. Parrish gave only praise for the national guard. Another reference Elsworth gives to support the claim of holding firefighters at gunpoint is only a summary of events in which they suppressed the firing of guns by the rioters and disarmed them of their firearms. Yet another of his references states that they were fired upon by the black 'mob', "It would mean a fireman's life to turn a stream of water on one of those negro buildings. They shot at us all morning when we were trying to do something but none of my men were hit. There is not a chance in the world to get through that mob into the negro district." By 4 am, an estimated two dozen black-owned businesses had been set ablaze.

As news traveled among Greenwood residents in the early morning hours, many began to take up arms in defense of their neighborhood, while others began a mass exodus from the city. Throughout the night both sides continued fighting, sometimes only sporadically.

Daybreak

Upon sunrise, around 5 a.m., a train whistle sounded (Hirsch said it was a siren). Some rioters believed this sound to be a signal for the rioters to launch an all-out assault on Greenwood. A white man stepped out from behind the Frisco depot and was fatally shot by a sniper in Greenwood. Crowds of rioters poured from their shelter, on foot and by car, into the streets of the black neighborhood. Five white men in a car led the charge, but were killed by a fusillade of gunfire before they had traveled one block.

Overwhelmed by the sheer number of white people, more black people retreated north on Greenwood Avenue to the edge of town. Chaos ensued as terrified residents fled. The rioters shot indiscriminately and killed many residents along the way. Splitting into small groups, they began breaking into houses and buildings, looting. Several black people later testified that white people broke into occupied homes and ordered the residents out to the street, where they could be driven or forced to walk to detention centers.

A rumor spread among the white people that the new Mount Zion Baptist Church was being used as a fortress and armory. Purportedly twenty caskets full of rifles had been delivered to the church, though no evidence was ever found.

Attack by air

Numerous eyewitnesses described airplanes carrying white assailants, who fired rifles and dropped firebombs on buildings, homes, and fleeing families. The privately owned aircraft were dispatched from the nearby Curtiss-Southwest Field outside Tulsa.

Law enforcement officials later said that the planes were to provide reconnaissance and protect against a "Negro uprising". Law enforcement personnel were thought to be aboard at least some flights. Eyewitness accounts, such as testimony from the survivors during Commission hearings and a manuscript by eyewitness and attorney Buck Colbert Franklin discovered in 2015, said that on the morning of June 1, men in the planes dropped incendiary bombs and fired rifles at black residents.

Richard S. Warner concluded in his submission to The Oklahoma Commission that there was no reliable evidence to support such attacks. Many supposed eyewitnesses, many years later reported witnessing explosions. Warner states that many newspapers targeted at black readers heavily reported the use of nitroglycerin, turpentine and rifles from the planes however many cited anonymous sources or second hand accounts from anonymous sources. Beryl Ford, one of the preeminent historians of the disaster, concluded from her vast collection of photographs that there was no evidence of any building damaged by explosions. Danney Goble commended Warner on his efforts and supported his conclusions. State representative Don Ross however dissented from the evidence presented in the report and the conclusions of three of Oklahoma's top experts concluding that bombs were dropped from planes.

William Joseph Simmons, Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, was appointed head of The Knights of the Air, May 20, 1921. The organization was described as a fraternal organisation for former air force officers. A spokesperson for the organisation publicly denounced the Ku Klux Klan and denied any connection.

New eyewitness account

In 2015, a previously unknown written eyewitness account of the events of May 31, 1921 was discovered and subsequently obtained by the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. The 10-page typewritten manuscript was authored by noted Oklahoma attorney Buck Colbert Franklin.

Notable quotes:

Lurid flames roared and belched and licked their forked tongues into the air. Smoke ascended the sky in thick, black volumes and amid it all, the planes—now a dozen or more in number—still hummed and darted here and there with the agility of natural birds of the air.

"Planes circling in mid-air: They grew in number and hummed, darted and dipped low. I could hear something like hail falling upon the top of my office building. Down East Archer, I saw the old Mid-Way hotel on fire, burning from its top, and then another and another and another building began to burn from their top."

'The side-walks were literally covered with burning turpentine balls. I knew all too well where they came from, and I knew all too well why every burning building first caught fire from the top.'"

I paused and waited for an opportune time to escape. 'Where oh where is our splendid fire department with its half dozen stations?' I asked myself. 'Is the city in conspiracy with the mob?'

Franklin states that every time he saw a white man shot, he "felt happy" and he, "swelled with pride and hope for the race."

Franklin reported seeing multiple machine guns firing at night and hearing 'thousands and thousands of guns' being fired simultaneously from all directions. He states that he was arrested by, "a thousand boys, it seemed,...firing their guns every step they took."

Arrival of National Guard troops

National Guard with wounded.

Adjutant General Charles Barrett of the Oklahoma National Guard arrived with 109 troops from Oklahoma City by special train about 9:15 am. Ordered in by the governor, he could not legally act until he had contacted all the appropriate local authorities, including the mayor T. D. Evans, the sheriff, and the police chief. Meanwhile, his troops paused to eat breakfast. Barrett summoned reinforcements from several other Oklahoma cities.

By this time, thousands of surviving black residents had fled the city; another 4,000 persons had been rounded up and detained at various centers. Under the martial law established this day, these detainees were required to carry identification cards.

Barrett declared martial law at 11:49 am, and by noon the troops had managed to suppress most of the remaining violence. A 1921 letter from an officer of the Service Company, Third Infantry, Oklahoma National Guard, who arrived May 31, 1921, reported numerous events related to suppression of the riot:

taking about 30-40 blacks into custody;

putting a machine gun on a truck and taking it on patrol;

being fired on from Negro snipers from the "Church" and returning fire; *

being fired on by white men;

turning the prisoners over to deputies to take them to police headquarters;

being fired upon again by negroes and having two NCOs slightly wounded;

searching for negroes and firearms;

detailing a NCO to take 170 Negroes to the civil authorities; and

delivering an additional 150 Negroes to the Convention Hall.

Stockpiled ammunition

Captain John W. McCune reported that stockpiled ammunition within the burning structures began to explode which may have further contributed to casualties.

End of martial law

Martial law was withdrawn Friday afternoon, June 4, 1921 under Field Order No. 7.

Aftermath

Little Africa on Fire. Tulsa Race Riot, June 1, 1921 Apparently taken from the roof of the Hotel Tulsa on 3rd St. between Boston Ave. and Cincinnati Ave. The first row of buildings is along 2nd St. The smoke cloud on the left (Cincinnati Ave. and the Frisco Tracks) is identified in the Tulsa Tribune version of this photo as being where the fire started.

Casualties

The riot was covered by national newspapers and the reported number of deaths varies widely. On June 1, 1921, the Tulsa Tribune reported that nine white people and 68 black people had died in the riot, but shortly afterwards it changed this number to a total of 176 dead. The next day, the same paper reported the count as nine white people and 21 black people. The New York Times said that 77 people had been killed, including 68 black people, but it later lowered the total to 33. The Richmond Times Dispatch of Virginia reported that 85 people (including 25 white people) were killed; it also reported that the Police Chief had reported to Governor Robertson that the total was 75; and that a Police Major put the figure at 175. The Oklahoma Department of Vital Statistics count put the number of deaths at 36 (26 black and 10 white). very few people, if any, died as a direct result of the fire. Official state records recorded only five deaths by conflagration for the entire state in the year of 1921.

Walter Francis White of the N.A.A.C.P. traveled to Tulsa from New York and reported that, although officials and undertakers said that the fatalities numbered ten white and 21 colored, he estimated the number of the dead to be 50 whites and between 150 and 200 Negroes; he also reported that ten white men were killed on Tuesday; six white men drove into the black section and never came out, and thirteen whites were killed on Wednesday; he reported that the head of the Salvation Army in Tulsa said that 37 negroes were employed as gravediggers to bury 120 negroes in individual graves without coffins on Friday and Saturday. The Oklahoma Commission report states that it was 150 graves and over 36 grave diggers. Ground penetrating radar was used to investigate the sites purported to contain these mass graves. Multiple eyewitness reports and 'oral histories' suggested the graves could have been dug at three different cemeteries across the city. The sites were examined and no evidence of ground disturbance indicative of mass graves was found however at one site ground disturbance was found in a five-meter squared area but cemetery records indicate that three graves had been dug and bodies buried within this envelope before the riot. The Los Angeles Express headline said "175 Killed, Many Wounded". Oklahoma's 2001 Commission into the riot placed the number of dead to likely be somewhere between 100-300 people. However this is based on a misquotation of the Red Cross Report, wherein the author states that the total number "is a matter of conjecture."

Of the some 800 people admitted to local hospitals for injuries, the majority are believed to have been white[citation needed], as both black hospitals had been burned in the rioting. Additionally, even if the white hospitals had admitted black people because of the riot, against their usual segregation policy, injured blacks had little means to get to these hospitals, which were located across the city from Greenwood. More than 6,000 black Greenwood residents were arrested and detained at three local facilities: Convention Hall, now known as the Brady Theater, the Tulsa County Fairgrounds (then located about a mile northeast of Greenwood), and McNulty Park (a baseball stadium at Tenth Street and Elgin Avenue).

Red Cross

The Red Cross, in their preliminary overview, mentioned wide-ranging external estimates of 55 to 300 dead however due to the hurried nature of undocumented burials declined to suggest an estimate of their own stating, "The number of dead is a matter of conjecture." The Red Cross registered 8624 persons, recorded 1256 residences burned and a further 215 residences looted as a part of their relief effort. 183 people were hospitalised, mostly for gunshot wounds or burns (they differentiate in their records on the basis of triage category not the type of wound) while a further 531 required first aid or surgical treatment with an estimated 10 000 persons left homeless. 8 miscarriages were attributed to be a result of the tragedy. 19 died in care between June 1 and the 30th of December.

I lived in Tulsa 30 years ago, and frequented a laundromat on Brady St where I met a man (caretaker of the laundromat) who was 10 at the time of the riots. I'd never heard of the event until I spoke to him, at length, about his experience during it. I still remember him saying, "You know, I had a lot of rage for a long time about it. I hated white people, but hate can't last forever. And I like you."

Israeli opposition parties reach agreement to oust Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu

Source: WaPo

By Shira Rubin

May 30, 2021 at 1:16 p.m. EDT

JERUSALEM — A diverse coalition of Israeli opposition parties said Sunday that they have the votes to form a unity government to unseat Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel’s longest-serving leader and its dominant political figure for more than a decade.

Under the agreement, reached after weeks of negotiations spearheaded by centrist opposition leader Yair Lapid, former Netanyahu defense minister and ally Naftali Bennett will lead a power-sharing government.

“We could go to fifth elections, sixth elections, until our home falls upon us, or we could stop the madness and take responsibility,” Bennett said in a televised statement Sunday evening. “Today, I would like to announce that I intend to join my friend Yair Lapid in forming a unity government.”

Netanyahu has been struggling to hold onto power after four inconclusive elections in the past two years while facing an ongoing corruption trial. Bennett is one of several former loyalists who have flirted with joining the so-called change coalition, a collection of parties that span the political spectrum but share a desire to end Netanyahu’s 12-year tenure.

-/snip-

Read more: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/israel-netanyahu-bennett-lapid/2021/05/30/af2df7b4-c11d-11eb-922a-c40c9774bc48_story.html

Charles Grodin, Familiar Face From TV and Film, Dies at 86

The actor Charles Grodin with the title dog in the hit 1992 family movie “Beethoven.”Credit...via Photofest

Mr. Grodin, who also appeared on Broadway in “Same Time, Next Year” and wrote books, was especially adept at deadpan comedy.

By Neil Genzlinger

May 18, 2021, 1:26 p.m. ET

Charles Grodin, the versatile actor familiar from “Same Time, Next Year” on Broadway, popular movies like “The Heartbreak Kid,” “Midnight Run” and “Beethoven” and numerous television appearances, died on Tuesday at his home in Wilton, Conn. He was 86.

His son, Nicholas, said the cause was bone marrow cancer.

With a great sense of deadpan comedy and the kind of Everyman good looks that lend themselves to playing businessmen or curmudgeonly fathers, Mr. Grodin found plenty of work as a supporting player and the occasional lead. He also had his own talk show for a time in the 1990s and was a frequent guest on the talk shows of others, making 36 appearances on “The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson” and 17 on “Late Night With David Letterman.”

Mr. Grodin was a writer as well, with a number of plays and books to his credit. Though he never won a prestige acting award, he did win a writing Emmy for a 1977 Paul Simon television special, sharing it with Mr. Simon and six others.

-/snip-

Cross gently, Mr Grodin.

Buddy Roemer, Louisiana's former Democrat-turned-Republican governor, dies at 77

https://www.theadvocate.com/baton_rouge/news/article_4e8cd89e-3676-11eb-b2fc-eb5c23580375.html?8946789045BY TYLER BRIDGES | STAFF WRITER MAY 17, 2021 - 8:54 AM

Buddy Roemer, who rode a message of reform in the 1987 governor’s race to vault over three challengers and “slay the dragon” — scandal-torn three-time Gov. Edwin Edwards — but who lost reelection four years later to the same rival, died Monday in Baton Rouge.

Roemer was 77. He had been ill for months.

Roemer was a Democrat-turned-Republican, but he seemed too independent and headstrong to fit well in either party. He never followed the precept that to get ahead in politics, you had to get along with other politicians. With his sharp mind, he understood all the angles of a political play but disliked the deal-making that came with being governor. And that limited what he could achieve.

"He was all about reform, but it didn’t always work in his favor because of the realities of politics at the state Capitol," said Bernie Pinsonat, a veteran political consultant.

-/snip-

Norman Lloyd Dies: 'St. Elsewhere' Actor Who Worked With Welles, Hitchcock & Chaplin Was 106

Norman Lloyd on Monday, and in 1942's "Saboteur"

Courtesy photo; Everett

By Erik Pedersen

May 11, 2021 2:13pm

Norman Lloyd, the Emmy-nominated veteran actor, producer and director whose career ranged from Orson Welles’ Mercury Theatre, Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur and acting with Charlie Chaplin in Limelight to St. Elsewhere, Dead Poets Society and The Practice, died May 10 in his sleep at his Los Angeles home. He was 106. A family friend confirmed the news to Deadline.

During one of the famous Lloyd birthday celebrations, Karl Malden said, ”Norman Lloyd is the history of our business.”

Blessed with a commanding voice, Lloyd’s acting career dates back to Orson Welles’ Mercury Theatre troupe, of which he was the last surviving member. He was part of its first production — a modern-dress adaptation of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar on Broadway in 1937.

He originally was cast in Welles’ epic Citizen Kane and accompanied the director to Hollywood. When the filmmaker ran into his proverbial budget problems, Lloyd quit the project and retuned to New York, later making his screen debut as the villainous spy who fell from the top of the Statue of Liberty in Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur (1942).

-/snip-

Cross gently, Norman.

100 Years Ago Today; USS R-14 (Submarine) became a sailing ship and made her way home

Seen here are the jury-rigged sails used to bring R-14 back to port in 1921; the mainsail rigged from the radio mast is the top sail in the photograph, and the mizzen made of eight blankets also is visible. R-14's acting commanding officer, Lieutenant Alexander Dean Douglas, USN, is at top left, without a hat.(Source: US Naval Historical Center).

USS R-14 (SS-91) was an R-class coastal and harbor defense submarine of the United States Navy. Her keel was laid down by the Fore River Shipbuilding Company, in Quincy, Massachusetts, on 6 November 1918. She was launched on 10 October 1919 sponsored by Ms. Florence L. Gardner and commissioned on 24 December 1919, with Lieutenant Vincent A. Clarke, Jr., in command.

After a shakedown cruise off the New England coast, R-14 moved to New London, Connecticut, where she prepared for transfer to the Pacific Fleet. In May, she headed south. Given hull classification symbol "SS-91" in July, she transited the Panama Canal in the same month and arrived at Pearl Harbor on 6 September. There, for the next nine years, she assisted in the development of submarine and anti-submarine warfare tactics, and participated in search and rescue operations.

R-14 — under acting command of Lieutenant Alexander Dean Douglas – ran out of usable fuel and lost radio communications in May 1921 while on a surface search mission for the seagoing tug Conestoga about 100 nmi (120 mi; 190 km) southeast of the island of Hawaii. Since the submarine's electric motors did not have enough battery power to propel her to Hawaii, the ship's engineering officer Roy Trent Gallemore came up with a novel solution to their problem. Lieutenant Gallemore decided they could try to sail the boat to the port of Hilo, Hawaii. He therefore ordered a foresail made of eight hammocks hung from a top boom made of pipe bunk frames lashed firmly together, all tied to the vertical kingpost of the torpedo loading crane forward of the submarine's superstructure. Seeing that this gave R-14 a speed of about 1 kn (1.2 mph; 1.9 km/h), as well as rudder control, he ordered a mainsail made of six blankets, hung from the sturdy radio mast (top sail in photo). This added .5 kn (0.58 mph; 0.93 km/h) to the speed. He then ordered a mizzen made of eight blankets hung from another top boom made of bunk frames, all tied to the vertically placed boom of the torpedo loading crane. This sail added another .5 kn (0.58 mph; 0.93 km/h). Around 12:30 pm on 12 May, Gallemore was able to begin charging the boat's batteries.] After 64 hours under sail at slightly varying speeds, R-14 entered Hilo Harbor under battery propulsion on the morning of 15 May 1921. Douglas received a letter of commendation for the crew's innovative actions from his Submarine Division Commander, CDR Chester W. Nimitz, USN.

-/snip-

27 residents of Newark & Clifton Springs nursing homes test positive for COVID-19

by: Ally Peters, Dan Gross, WROC Staff

Posted: May 7, 2021 / 04:05 PM EDT / Updated: May 7, 2021 / 04:13 PM EDT

NEWARK, N.Y. (WROC) — Dr. Robert Mayo, Chief Medical Officer of Rochester Regional Health announced on a Zoom press conference today that 27 residents between the DeMay Living Center in Newark, and Clifton Springs Nursing Home, have tested positive for COVID-19.

17 cases were reported at the DeMay facility, whereas 10 were reported from the other location.

https://twitter.com/allypetersnews/status/1390757002394099718

Dr. Mayo said that these cases were mainly identified through their regular testing, as 24 of the residents were asymptomatic, likely because they were previously vaccinated.

“The pandemic is still persisting, and it is really important to be vaccinated,” Dr. Mayo said.

One of the non vaccinated people have been hospitalized. Rochester Regional Health says it’s not clear how the virus was brought into the centers. They also don’t know if the cases were caused by a variant because that requires special testing.

-/snip-

84 Years Ago Today; "Oh, the humanity!"

The Hindenburg disaster occurred on May 6, 1937, in Manchester Township, New Jersey, United States. The German passenger airship LZ 129 Hindenburg caught fire and was destroyed during its attempt to dock with its mooring mast at Naval Air Station Lakehurst. On board were 97 people (36 passengers and 61 crewmen); there were 36 fatalities (13 passengers and 22 crewmen, 1 worker on the ground).

The disaster was the subject of newsreel coverage, photographs, and Herbert Morrison's recorded radio eyewitness reports from the landing field, which were broadcast the next day. A variety of hypotheses have been put forward for both the cause of ignition and the initial fuel for the ensuing fire. The event shattered public confidence in the giant, passenger-carrying rigid airship and marked the abrupt end of the airship era.

Disaster

At 7:25 p.m. local time, the Hindenburg caught fire and quickly became engulfed in flames. Eyewitness statements disagree as to where the fire initially broke out; several witnesses on the port side saw yellow-red flames first jump forward of the top fin near the ventilation shaft of cells 4 and 5.[4] Other witnesses on the port side noted the fire actually began just ahead of the horizontal port fin, only then followed by flames in front of the upper fin. One, with views of the starboard side, saw flames beginning lower and farther aft, near cell 1 behind the rudders. Inside the airship, helmsman Helmut Lau, who was stationed in the lower fin, testified hearing a muffled detonation and looked up to see a bright reflection on the front bulkhead of gas cell 4, which "suddenly disappeared by the heat". As other gas cells started to catch fire, the fire spread more to the starboard side and the ship dropped rapidly. Although there were cameramen from four newsreel teams and at least one spectator known to be filming the landing, as well as numerous photographers at the scene, no known footage or photograph exists of the moment the fire started.

Wherever they started, the flames quickly spread forward first consuming cells 1 to 9, and the rear end of the structure imploded. Almost instantly, two tanks (it is disputed whether they contained water or fuel) burst out of the hull as a result of the shock of the blast. Buoyancy was lost on the stern of the ship, and the bow lurched upwards while the ship's back broke; the falling stern stayed in trim.

As the tail of the Hindenburg crashed into the ground, a burst of flame came out of the nose, killing 9 of the 12 crew members in the bow. There was still gas in the bow section of the ship, so it continued to point upward as the stern collapsed down. The cell behind the passenger decks ignited as the side collapsed inward, and the scarlet lettering reading "Hindenburg" was erased by flames as the bow descended. The airship's gondola wheel touched the ground, causing the bow to bounce up slightly as one final gas cell burned away. At this point, most of the fabric on the hull had also burned away and the bow finally crashed to the ground. Although the hydrogen had finished burning, the Hindenburg's diesel fuel burned for several more hours.

The fire bursts out of the nose of the Hindenburg, photographed by Murray Becker.

The time that it took from the first signs of disaster to the bow crashing to the ground is often reported as 32, 34 or 37 seconds. Since none of the newsreel cameras were filming the airship when the fire started, the time of the start can only be estimated from various eyewitness accounts and the duration of the longest footage of the crash. One careful analysis by NASA's Addison Bain gives the flame front spread rate across the fabric skin as about 49 ft/s (15 m/s) at some points during the crash, which would have resulted in a total destruction time of about 16 seconds (245m/15 m/s=16.3 s).

Some of the duralumin framework of the airship was salvaged and shipped back to Germany, where it was recycled and used in the construction of military aircraft for the Luftwaffe, as were the frames of the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin and LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin II when both were scrapped in 1940.

In the days after the disaster, an official board of inquiry was set up at Lakehurst to investigate the cause of the fire. The investigation by the US Commerce Department was headed by Colonel South Trimble Jr, while Dr. Hugo Eckener led the German commission.

51 years Ago Today; Tin soldiers and Nixon's coming...

Mary Ann Vecchio gestures and screams as she kneels by the body of a student, Jeffrey Miller, lying face down on the campus of Kent State University, in Kent, Ohio.

The Kent State shootings, also known as the May 4 massacre or the Kent State massacre, were the shootings on May 4, 1970, of unarmed college students by members of the Ohio National Guard at Kent State University in Kent, Ohio, during a mass protest against the bombing of Cambodia by United States military forces. Twenty-eight guardsmen fired approximately 67 rounds over a period of 13 seconds, killing four students and wounding nine others, one of whom suffered permanent paralysis.

Some of the students who were shot had been protesting against the Cambodian Campaign, which President Richard Nixon announced during a television address on April 30 of that year. Other students who were shot had been walking nearby or observing the protest from a distance.

There was a significant national response to the shootings: hundreds of universities, colleges, and high schools closed throughout the United States due to a student strike of 4 million students,[10] and the event further affected public opinion, at an already socially contentious time, over the role of the United States in the Vietnam War.

Timeline

Thursday, April 30

President Nixon announced that the "Cambodian Incursion" had been launched by United States combat forces.

Friday, May 1

At Kent State University, a demonstration with about 500 students was held on May 1 on the Commons (a grassy knoll in the center of campus traditionally used as a gathering place for rallies or protests). As the crowd dispersed to attend classes by 1 p.m., another rally was planned for May 4 to continue the protest of the expansion of the Vietnam War into Cambodia. There was widespread anger, and many protesters issued a call to "bring the war home". A group of history students buried a copy of the United States Constitution to symbolize that Nixon had killed it. A sign was put on a tree asking "Why is the ROTC building still standing?"

Trouble exploded in town around midnight, when people left a bar and began throwing beer bottles at police cars and breaking windows in downtown storefronts. In the process they broke a bank window, setting off an alarm. The news spread quickly and it resulted in several bars closing early to avoid trouble. Before long, more people had joined the vandalism.

By the time police arrived, a crowd of 120 had already gathered. Some people from the crowd lit a small bonfire in the street. The crowd appeared to be a mix of bikers, students, and transient people. A few members of the crowd began to throw beer bottles at the police, and then started yelling obscenities at them. The entire Kent police force was called to duty as well as officers from the county and surrounding communities. Kent Mayor LeRoy Satrom declared a state of emergency, called the office of Ohio Governor Jim Rhodes to seek assistance, and ordered all of the bars closed. The decision to close the bars early increased the size of the angry crowd. Police eventually succeeded in using tear gas to disperse the crowd from downtown, forcing them to move several blocks back to the campus.

Saturday, May 2

City officials and downtown businesses received threats, and rumors proliferated that radical revolutionaries were in Kent to destroy the city and university. Several merchants reported that they were told that if they did not display anti-war slogans, their business would be burned down. Kent's police chief told the mayor that according to a reliable informant, the ROTC building, the local army recruiting station and post office had been targeted for destruction that night. There were rumors of students with caches of arms, plots to poison the local water supply with LSD, of students building underground tunnels for the purpose of blowing up the town's main store. Mayor Satrom met with Kent city officials and a representative of the Ohio Army National Guard. Following the meeting, Satrom made the decision to call Governor Rhodes and request that the National Guard be sent to Kent, a request that was granted. Because of the rumors and threats, Satrom believed that local officials would not be able to handle future disturbances. The decision to call in the National Guard was made at 5:00 p.m., but the guard did not arrive in town that evening until around 10 p.m. By this time, a large demonstration was under way on the campus, and the campus Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC) building was burning. The arsonists were never apprehended, and no one was injured in the fire. According to the report of the President's Commission on Campus Unrest:

Information developed by an FBI investigation of the ROTC building fire indicates that, of those who participated actively, a significant portion weren't Kent State students. There is also evidence to suggest that the burning was planned beforehand: railroad flares, a machete, and ice picks are not customarily carried to peaceful rallies.

There were reports that some Kent firemen and police officers were struck by rocks and other objects while attempting to extinguish the blaze. Several fire engine companies had to be called because protesters carried the fire hose into the Commons and slashed it. The National Guard made numerous arrests, mostly for curfew violations, and used tear gas; at least one student was slightly wounded with a bayonet.

Sunday, May 3

During a press conference at the Kent firehouse, an emotional Governor Rhodes pounded on the desk, pounding which can be heard in the recording of his speech. He called the student protesters un-American, referring to them as revolutionaries set on destroying higher education in Ohio.

We've seen here at the city of Kent especially, probably the most vicious form of campus-oriented violence yet perpetrated by dissident groups. They make definite plans of burning, destroying, and throwing rocks at police and at the National Guard and the Highway Patrol. This is when we're going to use every part of the law enforcement agency of Ohio to drive them out of Kent. We are going to eradicate the problem. We're not going to treat the symptoms. And these people just move from one campus to the other and terrorize the community. They're worse than the brown shirts and the communist element and also the night riders and the vigilantes. They're the worst type of people that we harbor in America. Now I want to say this. They are not going to take over [the] campus. I think that we're up against the strongest, well-trained, militant, revolutionary group that has ever assembled in America.

Rhodes also claimed he would obtain a court order declaring a state of emergency that would ban further demonstrations and gave the impression that a situation akin to martial law had been declared; however, he never attempted to obtain such an order.

During the day, some students came to downtown Kent to help with cleanup efforts after the rioting, actions which were met with mixed reactions from local businessmen. Mayor Satrom, under pressure from frightened citizens, ordered a curfew until further notice.

Around 8 p.m., another rally was held on the campus Commons. By 8:45 p.m., the Guardsmen used tear gas to disperse the crowd, and the students reassembled at the intersection of Lincoln and Main, holding a sit-in with the hopes of gaining a meeting with Mayor Satrom and University President Robert White. At 11:00 p.m., the Guard announced that a curfew had gone into effect and began forcing the students back to their dorms. A few students were bayoneted by Guardsmen.

Monday, May 4

On Monday, May 4, a protest was scheduled to be held at noon, as had been planned three days earlier. University officials attempted to ban the gathering, handing out 12,000 leaflets stating that the event was canceled. Despite these efforts, an estimated 2,000 people gathered on the university's Commons, near Taylor Hall. The protest began with the ringing of the campus's iron Victory Bell (which had historically been used to signal victories in football games) to mark the beginning of the rally, and the first protester began to speak.

Companies A and C, 1/145th Infantry and Troop G of the 2/107th Armored Cavalry, Ohio National Guard (ARNG), the units on the campus grounds, attempted to disperse the students. The legality of the dispersal was later debated at a subsequent wrongful death and injury trial. On appeal, the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit ruled that authorities did indeed have the right to disperse the crowd.

The dispersal process began late in the morning with campus patrolman Harold Rice riding in a National Guard Jeep, approaching the students to read an order to disperse or face arrest. The protesters responded by throwing rocks, striking one campus patrolman and forcing the Jeep to retreat.

Just before noon, the Guard returned and again ordered the crowd to disperse. When most of the crowd refused, the Guard used tear gas. Because of wind, the tear gas had little effect in dispersing the crowd, and some launched a second volley of rocks toward the Guard's line and chanted "Pigs off campus!" The students lobbed the tear gas canisters back at the National Guardsmen, who wore gas masks.

When it became clear that the crowd was not going to disperse, a group of 77 National Guard troops from A Company and Troop G, with bayonets fixed on their M1 Garand rifles, began to advance upon the hundreds of protesters. As the guardsmen advanced, the protesters retreated up and over Blanket Hill, heading out of the Commons area. Once over the hill, the students, in a loose group, moved northeast along the front of Taylor Hall, with some continuing toward a parking lot in front of Prentice Hall (slightly northeast of and perpendicular to Taylor Hall). The guardsmen pursued the protesters over the hill, but rather than veering left as the protesters had, they continued straight, heading toward an athletic practice field enclosed by a chain link fence. Here they remained for about 10 minutes, unsure of how to get out of the area short of retracing their path. During this time, the bulk of the students congregated to the left and front of the guardsmen, approximately 150 to 225 ft (46 to 69 m) away, on the veranda of Taylor Hall. Others were scattered between Taylor Hall and the Prentice Hall parking lot, while still others were standing in the parking lot, or dispersing through the lot as they had been previously ordered.

While on the practice field, the guardsmen generally faced the parking lot, which was about 100 yards (91 m) away. At one point, some of them knelt and aimed their weapons toward the parking lot, then stood up again. At one point the guardsmen formed a loose huddle and appeared to be talking to one another. They had cleared the protesters from the Commons area, and many students had left, but some stayed and were still angrily confronting the soldiers, some throwing rocks and tear gas canisters. About 10 minutes later, the guardsmen began to retrace their steps back up the hill toward the Commons area. Some of the students on the Taylor Hall veranda began to move slowly toward the soldiers as they passed over the top of the hill and headed back into the Commons.

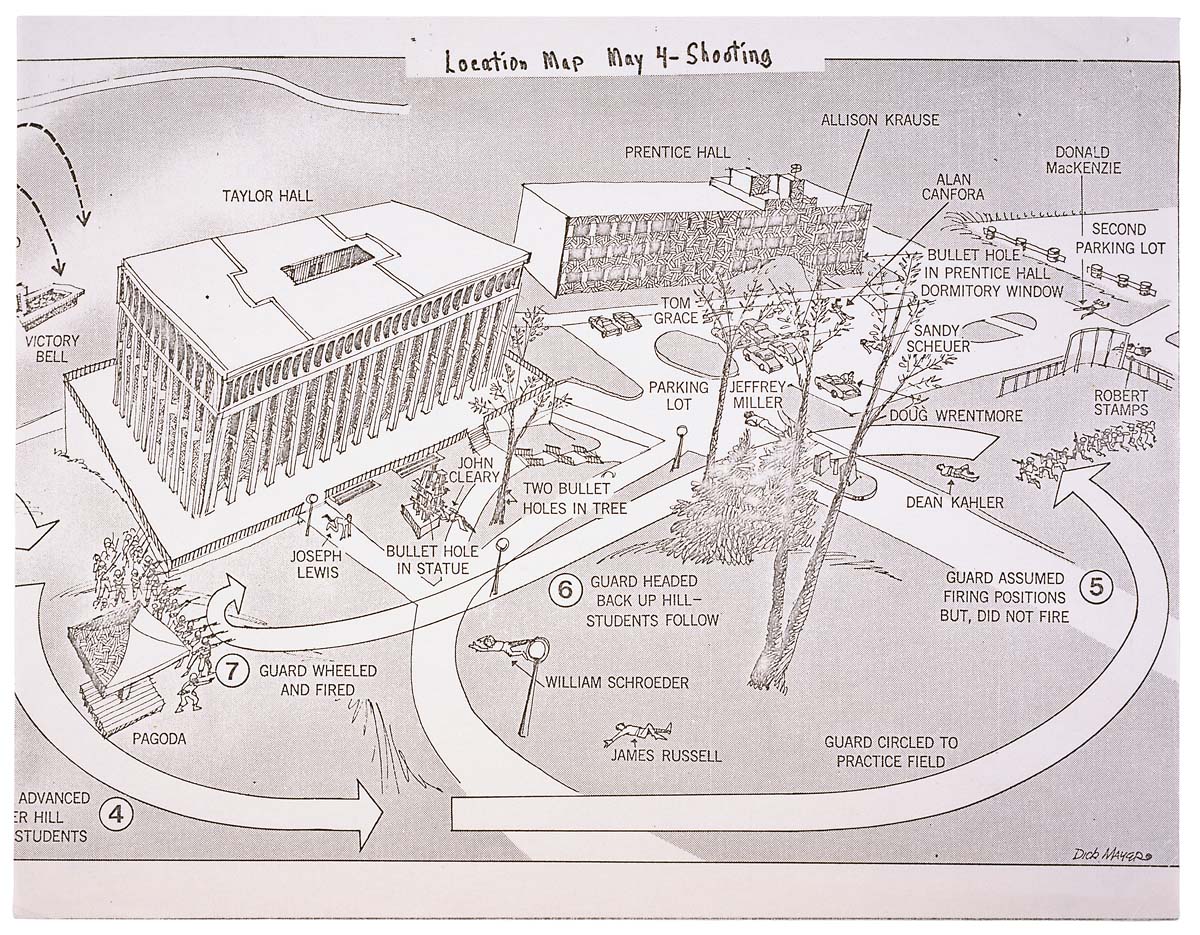

Map of the shootings

During their climb back to Blanket Hill, several guardsmen stopped and half-turned to keep their eyes on the students in the Prentice Hall parking lot. At 12:24 p.m., according to eyewitnesses, a sergeant named Myron Pryor turned and began firing at the crowd of students with his .45 pistol. A number of guardsmen nearest the students also turned and fired their rifles at the students. In all, at least 29 of the 77 guardsmen claimed to have fired their weapons, using an estimate of 67 rounds of ammunition. The shooting was determined to have lasted only 13 seconds, although John Kifner reported in The New York Times that "it appeared to go on, as a solid volley, for perhaps a full minute or a little longer." The question of why the shots were fired remains widely debated.

Photo taken from the perspective of where the Ohio National Guard soldiers stood when they opened fire on the students

Dent from a bullet in Solar Totem #1 sculpture by Don Drumm caused by a .30 caliber round fired by the Ohio National Guard at Kent State on May 4, 1970

The adjutant general of the Ohio National Guard told reporters that a sniper had fired on the guardsmen, which remains a debated allegation. Many guardsmen later testified that they were in fear for their lives, which was questioned partly because of the distance between them and the students killed or wounded. Time magazine later concluded that "triggers were not pulled accidentally at Kent State." The President's Commission on Campus Unrest avoided probing the question of why the shootings happened. Instead, it harshly criticized both the protesters and the Guardsmen, but it concluded that "the indiscriminate firing of rifles into a crowd of students and the deaths that followed were unnecessary, unwarranted, and inexcusable."

The shootings killed four students and wounded nine. Two of the four students killed, Allison Krause and Jeffrey Miller, had participated in the protest. The other two, Sandra Scheuer and William Knox Schroeder, had been walking from one class to the next at the time of their deaths. Schroeder was also a member of the campus ROTC battalion. Of those wounded, none was closer than 71 feet (22 m) to the guardsmen. Of those killed, the nearest (Miller) was 265 feet (81 m) away, and their average distance from the guardsmen was 345 feet (105 m).

Eyewitness accounts

Several present related what they saw.

Unidentified speaker 1:

Suddenly, they turned around, got on their knees, as if they were ordered to, they did it all together, aimed. And personally, I was standing there saying, they're not going to shoot, they can't do that. If they are going to shoot, it's going to be blank.

Unidentified speaker 2:

The shots were definitely coming my way, because when a bullet passes your head, it makes a crack. I hit the ground behind the curve, looking over. I saw a student hit. He stumbled and fell, to where he was running towards the car. Another student tried to pull him behind the car, bullets were coming through the windows of the car.

As this student fell behind the car, I saw another student go down, next to the curb, on the far side of the automobile, maybe 25 or 30 yards from where I was lying. It was maybe 25, 30, 35 seconds of sporadic firing.

The firing stopped. I lay there maybe 10 or 15 seconds. I got up, I saw four or five students lying around the lot. By this time, it was like mass hysteria. Students were crying, they were screaming for ambulances. I heard some girl screaming, "They didn't have blank, they didn't have blank," no, they didn't.

Another witness was Chrissie Hynde, the future lead singer of The Pretenders and a student at Kent State University at the time. In her 2015 autobiography she described what she saw:

Then I heard the tatatatatatatatatat sound. I thought it was fireworks. An eerie sound fell over the common. The quiet felt like gravity pulling us to the ground. Then a young man's voice: "They fucking killed somebody!" Everything slowed down and the silence got heavier.

The ROTC building, now nothing more than a few inches of charcoal, was surrounded by National Guardsmen. They were all on one knee and pointing their rifles at ... us! Then they fired.

By the time I made my way to where I could see them it was still unclear what was going on. The guardsmen themselves looked stunned. We looked at them and they looked at us. They were just kids, 19 years old, like us. But in uniform. Like our boys in Vietnam.

Gerald Casale, the future bassist/singer of Devo, also witnessed the shootings. While speaking to the Vermont Review in 2005, he recalled what he saw:

All I can tell you is that it completely and utterly changed my life. I was a white hippie boy and then I saw exit wounds from M1 rifles out of the backs of two people I knew.

Two of the four people who were killed, Jeffrey Miller and Allison Krause, were my friends. We were all running our asses off from these motherfuckers. It was total, utter bullshit. Live ammunition and gasmasks—none of us knew, none of us could have imagined ... They shot into a crowd that was running away from them!

I stopped being a hippie and I started to develop the idea of devolution. I got real, real pissed off.

Victims

Killed (and approximate distance from the National Guard):

Jeffrey Glenn Miller; age 20; 265 ft (81 m) shot through the mouth; killed instantly

Allison B. Krause; age 19; 343 ft (105 m) fatal left chest wound; died later that day

William Knox Schroeder; age 19; 382 ft (116 m) fatal chest wound; died almost an hour later in a local hospital while undergoing surgery

Sandra Lee Scheuer; age 20; 390 ft (120 m) fatal neck wound; died a few minutes later from loss of blood

Wounded (and approximate distance from the National Guard):

Joseph Lewis, Jr.; 71 ft (22 m); hit twice in the right abdomen and left lower leg

John R. Cleary; 110 ft (34 m); upper left chest wound

Thomas Mark Grace; 225 ft (69 m); struck in left ankle

Alan Michael Canfora; 225 ft (69 m); hit in his right wrist

Dean R. Kahler; 300 ft (91 m); back wound fracturing the vertebrae, permanently paralyzed from the chest down

Douglas Alan Wrentmore; 329 ft (100 m); hit in his right knee

James Dennis Russell; 375 ft (114 m); hit in his right thigh from a bullet and in the right forehead by birdshot, both wounds minor

Robert Follis Stamps; 495 ft (151 m); hit in his right buttock

Donald Scott MacKenzie; 750 ft (230 m); neck wound

Memorial to Jeffrey Miller, taken from approximately the same perspective as John Filo's 1970 photograph, as it appeared in 2007.

Profile Information

Member since: Wed Oct 15, 2008, 06:29 PMNumber of posts: 18,770