Latin America

In reply to the discussion: Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo founder Chicha Mariani finds granddaughter abducted in 1976. [View all]Judi Lynn

(164,122 posts)No doubt she had almost given up on her own hope. What a day it must have been when she learned her search was successful,

that her efforts had not been in vane, and that the child wanted to find her, as well.

[center]

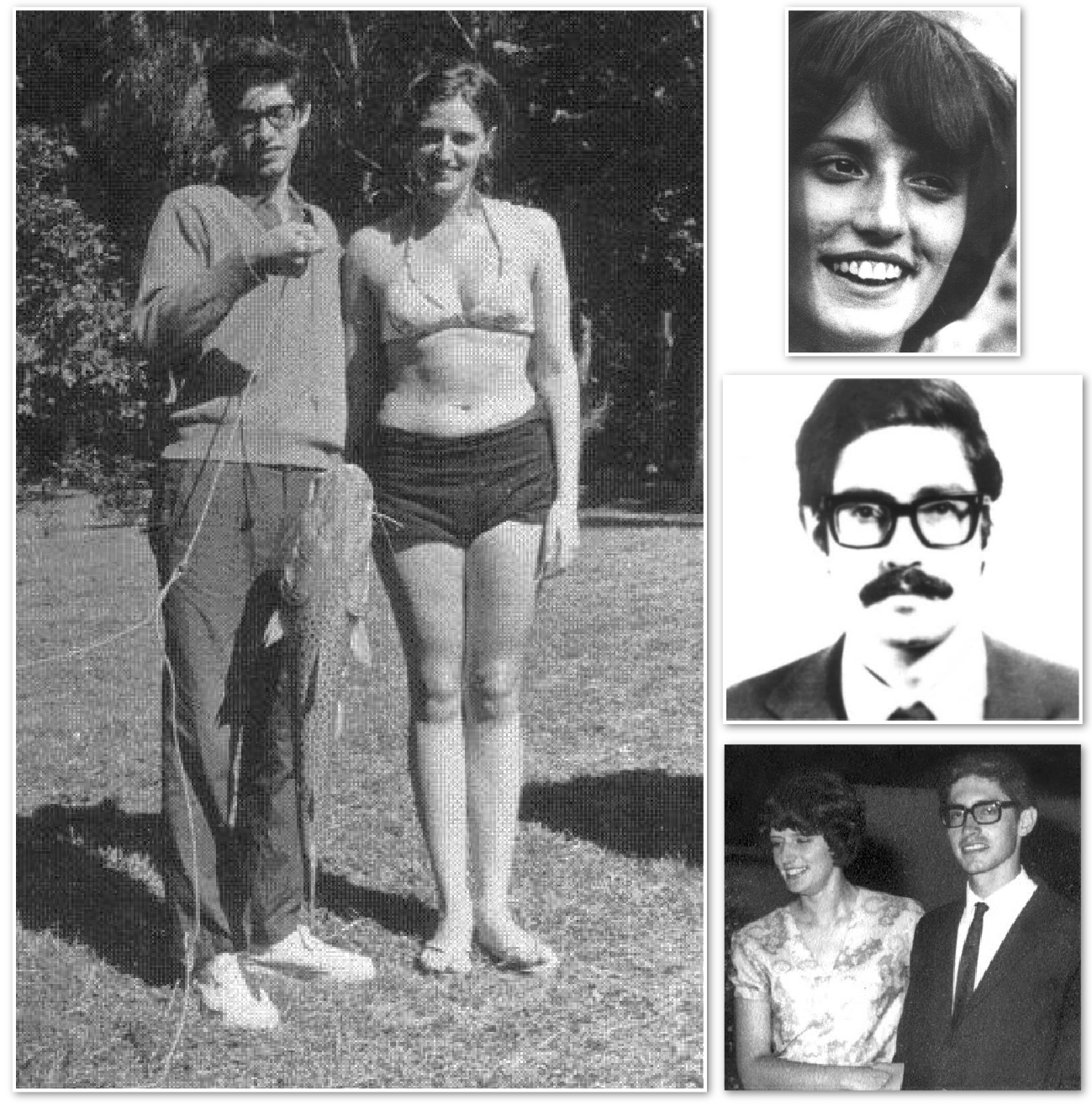

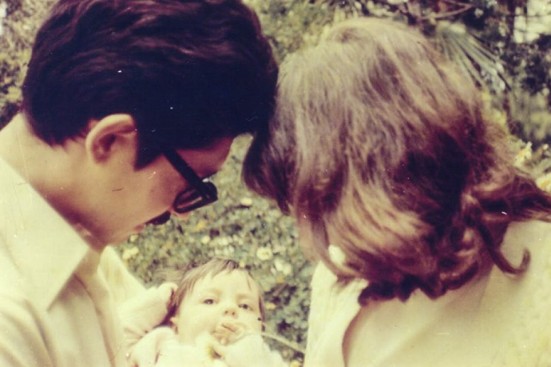

The lady's son and his wife, the parents of the granddaughter.

Clara Anahi's murdered parents, Daniel Mariani and Diana Teruggi.

[font size=1]

Chicha Mariani, at the bullet-scarred house of her son, daughter-in-law, and granddaughter. Armed forces attacked the house in 1976.

Photograph from Kameraphoto[/font]

[/center]

[/center]

A Reporter at Large

March 19, 2012 Issue

Children of the Dirty War

Argentina’s stolen orphans.

By Francisco Goldman

n November 24, 1976, eight months after a military junta took power in Argentina, launching the Dirty War that introduced the term los desaparecidos—“the disappeared”—to the world, a house in a peaceful, tree-lined neighborhood of La Plata, about forty miles southeast of Buenos Aires, came under attack. The assault, which involved two hundred armed forces on the ground and bombing and strafing from the air, lasted for four hours. María Isabel Chorobik de Mariani (known as Chicha), an art-history teacher who lived a few blocks away, heard it, as did others throughout the city. The next day, Mariani found out that it was her son’s house that had been attacked. Daniel Mariani, an economist, and his wife, a graduate student, were both members of the leftist guerrilla group known as the Montoneros. They had been in the house that day with their three-month-old daughter and three other militants. Neighbors called the building the House of Rabbits, because the people who lived there bred and sold rabbits, but that business was a front; the basement held the printing press that put out the underground newspaper Evita. The militants were only lightly armed. “They should have surrendered,” Mariani told me. Instead, they resisted.

Daniel, it turned out, had left for a meeting in Buenos Aires shortly before the attack. His wife, Diana Teruggi, was slain on the patio. She had hidden their daughter, Clara Anahí, in a bathtub, covered with towels. After the attack, a soldier found the baby and carried her out to the street. He asked the commander of the operation, Colonel Ramón Camps, what to do with her. Two police officers were sitting in a car nearby, and Camps told the soldier to give the baby to them. Thirty years later, a neighbor told Chicha Mariani that she had seen one of the policemen place Clara Anahí in an ambulance. When the policeman noticed her watching, he shouted at her to go back into her house or he’d kill her.

As soon as Mariani found out that her granddaughter had been in the house, she began to search for Clara Anahí, checking police stations, hospitals, juvenile courts, and churches. In months of looking, she found no trace of the child and no one who would discuss the situation with her. Even Mariani’s closest friends now crossed the street to avoid her. Finally, a woman working in a juvenile court took pity on her. “You’re very alone, Señora,” she said. She suggested that Mariani meet up with other women who were searching for missing children, and gave her the telephone number of Alicia de la Cuadra. De la Cuadra, whose daughter had been pregnant when she was “disappeared,” told Mariani about a group she belonged to—the Madres de Plaza de Mayo—which had been created in April, 1977, by mothers searching for children who had been detained by the military regime. The Madres gathered in front of the Presidential Palace in Buenos Aires every Thursday to march in silent protest around the plaza, wearing white kerchiefs embroidered with their missing children’s names. Mariani participated in a protest with the Madres and soon formed another group, with de la Cuadra and ten other Madres who were also looking for missing grandchildren. They became known as the Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo.

Mariani’s son, who had continued his militant life, was shot dead in a La Plata street eight months after the death of his wife. Years later, Mariani’s husband, a symphony conductor, still often hallucinated that the floors of their home were soaked with blood. He spent most of his time in Italy, and he died in 2003. Mariani stayed in La Plata and dedicated her life to finding Clara Anahí.

More:

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2012/03/19/children-of-the-dirty-war

Thank you, forest444!

What a loving triumph snatched from the jaws of defeat.