Latin America

In reply to the discussion: Escazu Agreement set to bring environmental justice down to earth [View all]Judi Lynn

(164,067 posts)Death in the Devil’s Paradise

Little over a hundred years ago, in March 1913, one of the least known, and most shameful, episodes in British colonial history was brought to an end in a London court room. The Peruvian Amazon Rubber Company was wound up in the High Court, the only hint at its dark secrets being a brief remark by the judge that ‘it was impossible to acquit the partners of knowledge of the way in which the rubber had been collected for the company’.

What is known today as the rubber boom had its origin in the middle of the nineteenth century, with Charles Goodyear’s discovery that cooking and treating latex harvested from rubber trees turned it into a product with a huge range of potential uses. With Henry Ford’s mass production of the motor car a few decades later, and the invention of tyres by John Dunlop in 1888, the need for rubber suddenly became extremely pressing.

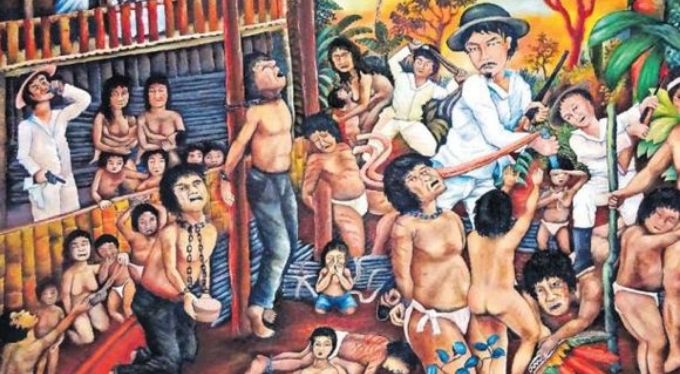

Thousands of Amazon Indians were enslaved and killed during the rubber boom

The rubber tree grew in profusion in the Amazon, especially in its western fringes, and soon a veritable ‘rubber rush’ was on. Entrepreneurs and fortune-seekers set off into the steamy jungle determined to cash in. Unaware of the impending disaster, tens of thousands of Indians for whom the western Amazon was home were experiencing their last years of peace.

One of the many chancers and treasure-seekers determined to make their fortunes in this brave new world was a Peruvian trader named Julio Cesar Arana. Arana acquired vast estates in a region named after its largest river, the Putumayo, and, as many others were doing at the time, realized that only by enslaving huge numbers of the local Indians to collect the latex could his visions of vast wealth become reality. (Slavery had, of course, been abolished decades earlier in the US, but brazenly continued in Amazonia).

Arana and his brother, the aptly-named Lizardo, moved quickly, bringing to Peru from Barbados a large number of overseers well-used to cracking the whip on workers in the British sugar-cane estates. The Bora, Witoto, Andoke and other tribes living in the Putumayo basin were quickly enslaved, and those who escaped the appalling treatment inflicted on them soon fell victim to waves of epidemics brought into remote rivers by traders and rubber-tappers.

In a few short years, thousands of Indians were killed or died from mistreatment or disease. The outside world remained unaware of the horrors the Arana brothers’ empire was perpetrating until 1909, when a young American engineer, Walter Hardenburg, who had traveled through the region the year before and been held prisoner by the Arana brothers, wrote several articles for the magazine Truth.

Hardenburg’s account of the abuses he had witnessed makes horrifying reading even today. ‘The agents of the Company force the pacific Indians of the Putumayo to work day and night… without the slightest remuneration except the food needed to keep them alive. They are robbed of their crops, their women and their children… They are flogged inhumanly until their bones are laid bare… They are left to die, eaten by maggots, when they serve as food for the dogs… Their children are grasped by the feet and their heads are dashed against trees and walls until their brains fly out… Men, women and children are shot to provide amusement… they are burned with kerosene so that the employees may enjoy their desperate agony.’

More:

https://www.survivalinternational.org/articles/3282-rubber-boom

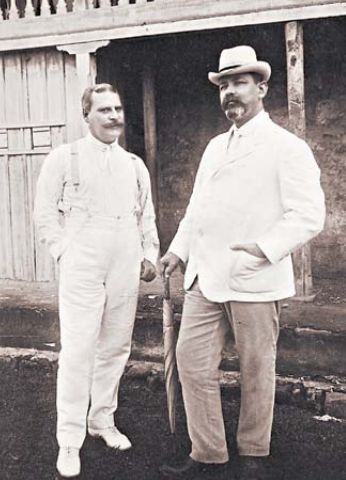

Julio Cesar Arana, the great rubber baron

Cristina Alvarado Ortiz 8 months ago

Google translation:

Between the years 1882 and 1912 the so-called "Rubber Boom" was a holocaust for Amazonian indigenous peoples such as the Huitotos, Boras and Andokes. Julio Cesar Arana was one of the Peruvians who marked the history of our country with his ambition. Little is known about the childhood and youth of this character who emerged from poverty as one of the most powerful and ruthless men in the history of Peru. In this chronicle we will learn more about its history.

Julio Cesar Arana on the right. Source: El Comercio

. . .

His travels through the jungle as a vendor of supplies made him understand how easy it was to get the rubber tappers into debt by providing them with supplies and how important it was that they pay him in rubber and not with soles. Rubber used to rise in price in an unusual way, so it was earning up to four times what it invested.

. . .

Thus, Arana, acquired some land where rubber trees were grouped. But the real problem was who would extract the rubber. They could not be Asian or European workers, as they ended up decimated by disease.

The only ones who could carry out this task were the Indians, who were used to these pathogenic scenarios, or some human group that had no other option but to work in that environment. The latter was why Julio Cesar went, together with his brother-in-law, to Caerá, in the north of Brazil: he was going to recruit those who would extract his first rubber plantation.

Precisely this region was prone to prolonged and ferocious droughts for which its inhabitants had to migrate to other states or countries. It was in this exodus that a group ran into Julio Cesar Arana. It did not matter to him that they did not speak Spanish, since the only important thing was that they could extract the rubber.

The rubber tapper was indebted to be able to control him in perpetuity. In the first place, he charged the passage to the Yurimaguas at about thirty pounds sterling each; the tools needed to collect rubber, weapons, and supplies were also added to their debts. Nothing was free and Arana felt safe with this system because, according to his accounting books, three months of continuous work was not enough to pay off his debts. What's more, he didn't give them time to fish or hunt; in this way the debts increased with each new order for provisions.

. . .

Julio Cesar was making a prestigious name for himself in Iquitos. He was considered a prosperous rubber tapper and began promoting educational initiatives throughout the town. The first of his trips to Putumayo was in 1901; then it took almost fifteen days to be able to arrive. When he was in La Chorrea, a stop on the long journey, he did business, but he also got to know the Huitotos, an Amazonian community characterized by its passivity.

Possibly he has thought of the gains he would make by subduing this town for nothing, how easy it would be. Julio Cesar Arana saw the native Indians as the only ones who could work and survive in that habitat where the valuable rubber was.

When he returned, he was given a great position: mayor of Iquitos from 1902. His administration, which lasted a year, was one of constant absences since rubber was a priority in his life. Arana did not stop indebting his rubber tappers who, in reality, assumed themselves as part of his company. As his debts grew, Arana was able to make the most of his manpower.

The price of rubber rose every day to exorbitant levels and thus, in a short time, Arana was creating a great empire at the cost of debts and human miseries. Within a few years, Arana became the richest man in Peru. His empire was supported by his relatives and the government never condemned his injustices.

https://medialab.unmsm.edu.pe/chiqaqnews/julio-cesar-arana-el-gran-baron-del-caucho/