Rare Carbon, Nitrogen, and Oxygen Isotopes Appear Abundant in a Young Planetary Nebula. [View all]

The paper I'll discuss in this post is this one: Extreme 13C,15N and 17O isotopic enrichment in the young planetary nebula K4-47 (Ziurys et al Nature 564, 378–381 (2018))

Some background:

Carbon has two stable isotopes, 12C and 13C; Nitrogen has two as well, 14N and 15N; Oxygen has three, 16O, 17O, and 18O.

All of the atoms in the universe except for hydrogen, a portion of its helium and a fraction of just one of lithium’s isotopes, 7Li, have been created by nuclear reactions after the “big bang.” The majority of these reactions took place in stars, with some important exceptions: Lithium’s other isotope, 6Li practically all of the beryllium in the universe, and all of its boron. (Lithium, beryllium, and boron are not stable in stars, and all three are rapidly consumed in them; they all exist because of nuclear spallation reactions driven by cosmic rays in gaseous interstellar clouds.)

For the uninitiated, writing a nuclear reaction in the format 14N(n,p)14C means that a nucleon, in this case nitrogen’s isotope with a mass number of 14 is struck by a neutron (n) and as a consequence ejects a proton (p) to give a new nucleon, carbon’s radioactive isotope having a mass number of 14.

In the case of carbon, the nuclear reaction just described has been taking place in Earth’s atmosphere ever since that atmosphere formed with large amounts of nitrogen gas in it. Thus a third radioactive isotope of carbon occurs naturally from the 14N(n,p)14C reaction in the atmosphere as a result of the cosmic ray flux from deep space and protons flowing out of the sun. However, since carbon 14 is radioactive and since the number of radioactive decays depends proportionately on the amount of atoms that exist, it eventually reaches a point at which it is decaying as fast as it is formed. We call this “secular equilibirium.” The long term secular equilibrium at which carbon 14 is formed in the atmosphere at the same rate at which it is decaying is the basis of carbon dating. (This secular equilibrium has been disturbed by the input of 14C as a result of nuclear weapons testing.) Even with the injection of 14C as a result of nuclear testing, 14C remains nonetheless extremely rare and for most purposes other than dating, can be ignored, except perhaps by radiation paranoids.

In the case of all three elements mentioned at the outset, the isotopic distribution in the immediate area of our solar system is dominated in each case by a single isotope: On Earth Carbon is 98.9% 12C; Nitrogen is 99.6% 14N; Oxygen is 99.8% 16O. The abundances vary only very slightly in the sun.

An interesting nuclear aside: 14N has a very unusual property: It is the only known nuclide to be stable while having both an odd number of neutrons and an odd number of protons. No other such example is known. Note the correction to this statement by a clear thinking correspondent in the comments below.

In recent years, I've been rather entranced by the interesting properties of the fissionable actinide nitrides, in particular the mononitrides of uranium, neptunium and plutonium and their interesting and likely very useful properties, and in this sense I've been sort of wistful over the low abundance of 15N in natural nitrogen. In an operating nuclear reactor, with a high flux on neutrons - in the type of reactors I think the world needs, fast neutrons - the same nuclear reaction that takes place in the upper atmosphere, the 14N(n,p)14C reaction, takes place. Thus the inclusion of the common isotope of nitrogen in nitride nuclear fuels will result in the accumulation of radioactive carbon-14. In this case, given 14C’s long half-life, around 5,700 years – much longer than the lifetime of a nuclear fuel – secular equilibrium will not occur while the fuel is being used.

Personally this doesn't bother me, since it avoids the unnecessary expense (in my view) of isolating nitrogen’s rare isotope, 15N, and because carbon-14 has many interesting and important uses already. Carbon-14’s nuclear properties are also excellent for use in carbide fuels, inasmuch as it has a trivial neutron capture cross section compared to carbons two stable isotopes and, without reference to the crystal structure of actinide nitrides and mean free paths therein, and without reference to the scattering cross section of the nuclide (which I don't have readily available), it takes 15% more collisions (for C14 to moderate (slow down) fast neutrons from 1 MeV (the order of magnitude at which neutrons emerge during fission) to thermal (0.253 eV) neutrons than it takes for carbon’s common isotope 12C. (Cf, Stacey, Nuclear Reactor Physics, Wiley, 2001, page 31.) Thus 14C is a less effective moderator, and thus has superior properties in the "breed and burn" type reactors I favor, reactors designed to run for more than half a century without being refueled, reactors designed to run on uranium’s most common isotope, 238U rather than the rare isotope, 235U, currently utilized in most nuclear reactors today. Over the many centuries it would take to consume all of the 238 already mined and sometimes regarded as so called “nuclear waste,” access to industrial amounts of carbon-14 might well prove very desirable for the purposes of neutron efficiency.

Anyway...

The dominance of the major isotopes of carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen in our local solar system and in much of the universe is a function of stellar synthesis. Most stable stars destined to have lives measured in billions of years, including our sun, actually run on the CNO cycle, in which the nuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium takes place catalytically rather than directly.

Here's a picture showing the CNO cycle pathways:

Six of the nuclei in this diagram are stable, the aforementioned 12C, 13C, 14N, 15N, 16O, and 17O. However only 3 of them occur in other pathways, 12C, 14N, and 16O. When a main sequence star is very old and has consumed nearly all of its hydrogen, the only nuclei left to "burn" is 4He. The problem is that 4He has much higher binding energy than its nearest neighbors, including putative beryllium isotopes. Here is the binding energy curve for atomic nuclei, the higher points being the more stable with respect to the lower points:

Helium-4's anomalous stability prevents the formation of the putative isotope Beryllium-8. Observation of this isotope of beryllium is almost impossible since it's half-life is on the order of ten attoseconds, and it cannot actually form in stars. This is why 12C is a critical element in the pathway to the existence of all heavier elements. It forms from the simultaneous fusion of three helium atoms, and exists because it is more stable than helium-4. This is exactly what happens in dense stars when they have run low or out of hydrogen and only have helium left to burn. Carbon-12 can fuse with helium-4 to form oxygen-16. In addition, it can fuse with residual deuterium (2H) under these circumstances to form nitrogen-14. (However, in the helium burning phase deuterium, which forms from the p(p,γ )d reaction, where d is deuterium nuclei, is also relatively depleted.) Thus the formation of these isotopes is independent of the CNO cycle. As a result, it turns out that after hydrogen and helium which together account for 98% of the universe’s elemental mass, oxygen and carbon are respectively the third and fourth most common elements. These four elements comprise 99.5% of the elemental mass of the universe. All other elements, with nitrogen included, turn out to be minor impurities in the universe as a whole.

The minor isotopes in the CNO cycle are actually consumed in stars in this model, and to the extent that they exist, they simply raise the catalytic rate of hydrogen consumption.

All of this is the “understanding,” at least.

According to the authors of the paper cited at the outset, however, there seems to be other things going on in the universe, places where these reactions and their effects do not dominate. The authors are studying, at microwave and other frequencies, a planetary nebula that is estimated to be only 400-900 years old.

From the introductory text in the paper:

From the abstract of the paper, touching on the unusual nature of what the authors are seeing:

... These results suggest that nucleosynthesis of carbon, nitrogen and oxygen is not well understood and that the classification of certain stardust grains must be reconsidered.

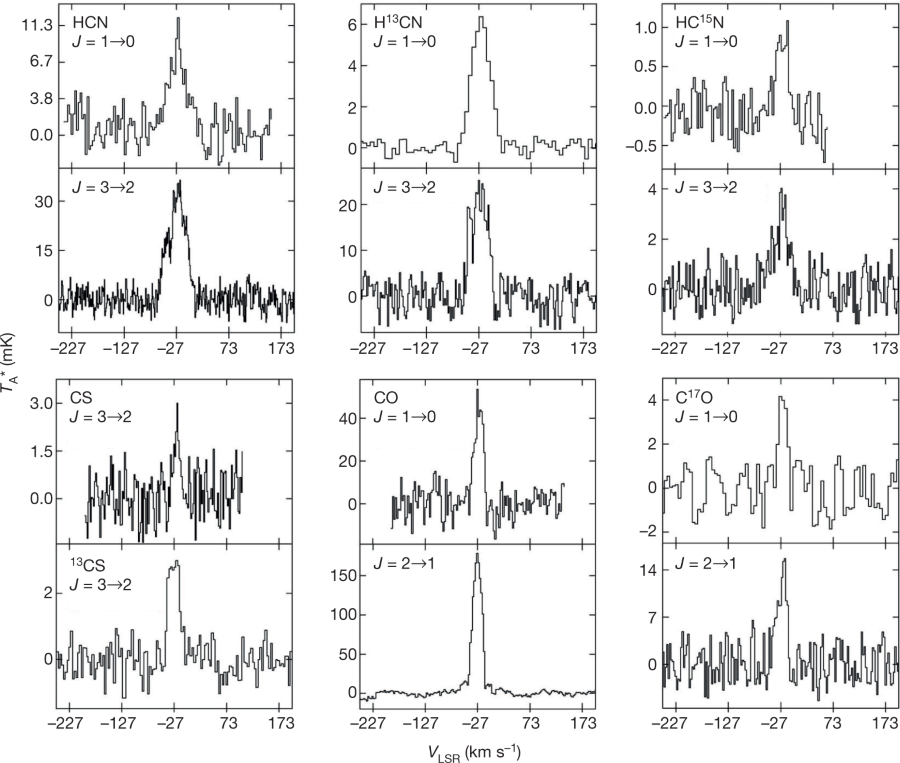

They describe in the body of the paper the molecules they find that allow them to identify the isotopes, from the vibrational frequencies of their rotations which are effected by these, the frequencies being effected by the masses at the atoms of which they are constructed. (In the paper the techniques for the sensitive detection of these frequency variations is described.)

Figure 2:

The caption:

Some further remarks:

A note on the rarity of this finding:

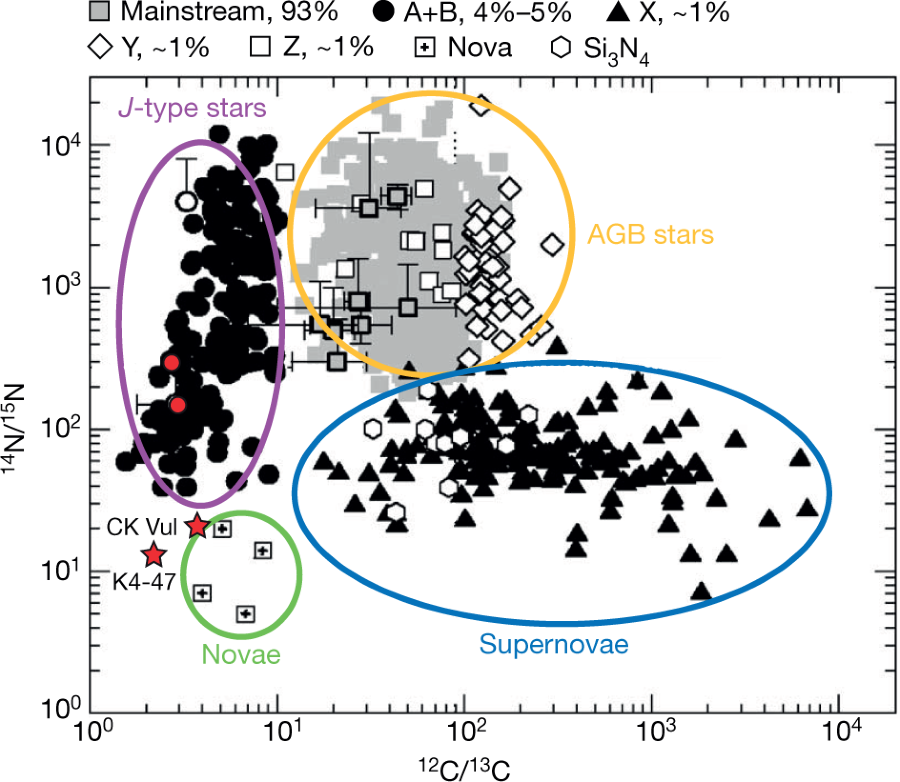

Aside from K4-47 and CK Vul, similarly low 12C/13C, 14N/15N and 16O/17O ratios have been found in presolar grains—small, 0.1–20-μm-sized particles extracted from meteorites28. These grains are known to predate the Solar System and originate in the circumstellar envelopes of stars that have long since died.

There is some discussion of the current theories of the origins of presolar grains, comprised largely of silicon carbide, thought to originate from "AGB" (Asymptotic giant branch) stars.

A graphic on this topic from the paper:

The caption:

Some final comments from the authors before technical discussions of methods:

50 years after the "Earth-rise" picture from Apollo 8 gave us a sense of our planetary fragility coupled with its magnificence, the rise of intellectually deficient, self absorbed fools, of which the asinine criminal Donald Trump is just one example, has threatened all that lives on that jewel planet first photographed from the orbit of the moon.

One feels the tragedy.

But the universe goes on, and for me, in this holiday season, it is good to feel its eternity, the beautiful facts that have no reason to be found other than that they are beautiful. In the grand scheme, I'm not sure we matter.

I wish you the best holiday season, and the peace that I found in this little paper, and that I wish that you, in your own place and own way, will similarly find.